Monday, June 30, 2025

Just This Darkness

Maybe 15 was too young to see BLUE VELVET. But that’s in the past. And I did see that David Lynch film when it came out, at Yonkers Movieland on opening weekend or close to it in the fall of 1986 and all this was at a point when I wasn’t having trouble getting into R-rated movies anymore. It’s very possible that first time was maybe the closest I will ever come to the feeling of seeing PSYCHO when it first opened back in 1960, like seeing into the possible future of what films might become, revealing something completely new and unexpected. I knew then that it was one of the best films I’d ever seen. I still know it now. Returning to the film each time places it once again in the context of David Lynch’s entire career and every time I revisit a David Lynch film it feels like the one that I’m watching is my favorite. But really, it’s probably BLUE VELVET. And MULHOLLAND DRIVE. And the entire run of TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN. Regardless, every David Lynch film contains a power that can take me back to that certain time in my life I was first discovering it, the way every one of them causes my brain to explode to make it feel like I’m back in a time when I was first discovering certain films and wanted to do nothing more than talk about them endlessly. BLUE VELVET was one of the first of these for me, one of those key films that I saw around this time (BRAZIL was another about six months earlier) that made me think, ‘this is what movies are?’ and it came at an age when I was open to it as well as lucky I didn’t have parents who were against me seeing a film like this. Or more likely that they had other things going on and weren’t paying very close attention.

And now, in the present, David Lynch is gone. It still doesn’t seem right. Several days after it happened back in January, I was flying out of Burbank early one morning but first stopped off at Bob’s Big Boy in Toluca Lake, so early the sun wasn’t up yet, to see the impromptu memorial that had sprouted there and pay my respects. Much of that week was spent thinking about all those ways his films mean so much to me, how much they affected me, how much they continue to stay with me. As awful as his passing was, the overwhelming response of pure love to that tragedy remains just about the most wonderful thing of this horrible year, a reminder of the beauty he inspires in people as things all around us drown in a sewer. That’s what he shows us. The beauty among the ugliness. The light seen in the dark. The love mixed with the hate. The whole world that’s wild at heart and weird on top. And we still see all that in our dreams.

But back to the past, which is also what BLUE VELVET gets me to think about. The town of Lumberton where it’s set feels like a sort of purgatory for its lead character. One of those periods when you’re not in high school or college, where you might find yourself stranded for some months when things haven’t gone the way you wanted, ready to start your life but you’re stuck there walking certain streets where you used to know people only by then they’re all gone. It all ends. The darkness falls. In your mind, in your memory, that town is always going to be the same. That’s how it is for me and the place where I grew up. To this day, it’s hard for me to ever think anything sexual about that place, it never seemed to exist there which maybe is what you’re supposed to think about the town where you grew up anyway. It’s supposed to be the beginning. Writing something on Facebook after he passed, I found myself typing out, “Seeing a David Lynch film for the first time was like seeing what the world could be.” Not should be. Not what it is. But what it sometimes feels like is there, some sort of power in the air that you weren’t aware of, waiting to be discovered. The world that we know is possible, much as we don’t always want to see it.

When his father is hospitalized, college student Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) returns home to Lumberton, North Carolina to help and work at the family hardware store. One day after visiting the hospital, Jeffrey is walking home through a vacant lot when he discovers a human ear on the ground. Taking it to the police, he meets Detective Williams (George Dickerson) and soon visits him at home to learn more about the case. There he meets his daughter Sandy (Laura Dern) who tips him off about lounge singer Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) who may have a connection to what her father is investigating. Still curious, Jeffrey comes up with the idea to sneak into her apartment late at night to learn more and enlists Sandy’s help, but when he gets inside and encounters the woman, he discovers her connection to the terrifying criminal Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) who may be more dangerous than he ever imagined.

The thing is, so many films fade. You outgrow them, you disconnect from them, they don’t have the power over you they once did. Looking back at it now, 1986 feels like the depths of the decade that was the 80s, some of the biggest films released during that period are forever connected to the cultural rot of the time. BLUE VELVET feels like it’s an integral part of the ‘80s yet defiantly disconnected from the decade, in the dividing line between then and the ‘50s iconography that is there on the edges adding so much that maybe this is the film that should have been called BACK TO THE FUTURE. This is, after all, the film that really has something to say about how one affects the other, how the past wasn’t as sweet as we want to think it was and no matter what has happened since, the future still contains the possibility of hope. On a very basic level the thriller plot of the film is still so enormously effective but the power the entire film holds is so much more than that, still feeling surprising while going so much further than any other film that has tried to do the same and whether the moment becomes a sly joke or the most terrifying sight imaginable the frisson it provides is unlike anything else, all coming together as part of this strange world.

It always feels a little nebulous what stage of life Kyle MacLachlan’s Jeffrey Beaumont is in. Maybe that’s because he’s not sure either. If anything, he’s in a holding pattern, home from school, not sure if he’ll be able to ever go back. Viewing the state his father is in, he needs to suddenly become an adult for the first time and is still trying to put that off as long as possible with this new project he begins for himself. He really has no one to tell him otherwise. You’re older and you suddenly find yourself trying to talk to a father who can’t speak and can’t help while the mother stays focused watching a TV that always seems to contain some sort of noirish crime show playing on it, depicting a life that presumably is far away from the sort of place Lumberton is. And, of course, Jeffrey is bored, just as you’re going to be in a small town, stuck in a place that may as well be a black hole of darkness as seen in the cutaways to the empty sidewalk in front of Jeffrey and Sandy, the trees overhead, the nightmarish darkness of the quiet neighborhood stretching out in front of them forever. The house that he points out where a childhood friend once lived who moved away doesn’t seem to have someone new living there, it just looks abandoned. It’s the end of his childhood and the whole place looks dead to him so naturally he’s going to stumble upon a strange body part lying on the ground. The theme of discovering the ugliness that lies below a tranquil surface almost seems simple now all these years later but it’s something he becomes forced to learn. Maybe in places like that you need to be reminded. “Here’s to an interesting experience,” he says to Sandy as they drink their Heineken at the beginning of it all, when he has no idea what’s coming.

On a very basic level, BLUE VELVET remains an extraordinary film in everything it does, the terror and humor of the world it’s set in, the way things unfold and how far it wants to go. Of course, everything that happens feels like it has some extra level of meaning. At this early stage the idea of narrative is still very much a part of what Lynch is doing. This would become more fractured as time went on and something like LOST HIGHWAY may be a puzzle to decipher but it also is much less of a strict linear plot than this film is. One thing which sets BLUE VELVET apart from all sorts of other thrillers, besides how normal they all seem in comparison, is that Jeffrey Beaumont isn’t thrust into this world against his will. He’s not a Hitchcockian everyman on the run for something he didn’t do, but another Hitchcockian lead like the one in VERTIGO who gets drawn further and further into the story even before he realizes it. Jeffrey didn’t have to get involved with any of this and in that dreamlike way, no matter what he says, it all seems like he does it for some unconscious reason that can never be fully explained. It’s a tone where adhering to a strict version of reality is never the biggest concern so we don’t know specifically what malady befell Jeffrey’s father, we don’t need a scene with a doctor who explains he had a stroke and yadda yadda, just as we don’t know exactly what Frank is inhaling each time he comes into Dorothy’s apartment. We never even have Dorothy explicitly tell us things from her own point of view and how she feels about it. We know enough just from looking at her. It's the imagery and the feeling that matters, not the specifics of the language. And we don’t know why Jeffrey is doing this at first. Maybe he’s just looking for that interesting experience, maybe just wanting to get involved in a Hardy Boys sort of mystery while he’s bored amidst the cheeriness of that hardware store and sitting around at home. Eventually he does say that it’s because this is something that has always been hidden, he’s finding something more than what’s on the surface in his lazy small town where presumably everyone is smiling and cheerful. But he seems to know that the Deep River Apartments nearby over on Lincoln contains a darkness where he shouldn’t go, it’s like that feeling is already inside of him, he’s just never been able to see it up close. When he’s discovered in the closet and Dorothy tells him to get undressed, the framing places her within his raised arm so it’s like she’s already inside of him, and even though we don’t see the full extent of his reaction when Dorothy begins kissing him way down below still holding that knife in her hand ready to use it, we don’t need to. We just know. And she knows what he’s there for.

Dorothy Vallens looks right at home in the beautiful, haunting, alien set of the seedy elegance that is her apartment, where it all gets revealed just as the fantasy she presents singing at The Slow Club. She likes to sing “Blue Velvet,” taking the cheeriness of that song heard at the beginning and turning it into a dark entry for Jeffrey as he wanders into this world, Sandy glancing over at him as he gazes at the older woman, not knowing what he might be thinking, not knowing if he’s a detective or pervert. Whatever Dorothy is ever thinking about seems indescribable, wearing a wig that makes her seem slightly off no matter how much she appears to be the most beautiful woman in the world, absurdly and painfully beautiful, yet there’s something about her that makes you want to look away. Sandy, meanwhile, is the vision of light in another part of Lumberton, introduced emerging from the dark, still going to high school with a presumably normal boyfriend who plays football and for some reason has a Montgomery Clift photo on her wall, making me imagine him turning up on TWIN PEAKS at age 70 if he had lived that long. Sandy has her dreams of love and through that comes her very sincere belief that it can spread into the world but it’s not as easy as she ever thinks, her plan of honking the horn to warn Jeffrey in the apartment is a good one but she can’t warn him about what’s coming. He needs to enter that world on his own. Sandy is the light emerging from the dark, open and honest unlike the cryptic nature of the other woman, willing to fight her way through it and offer forgiveness. When Jeffrey finally hits Dorothy after her protests, it’s what she desperately wants, what she desires, and it turns the two of them into something else altogether. When she’s seen in the light, the only time she’s seen outside during the day, and she still seems unable to keep from thinking of the dark for very long, still forever haunted by what has happened.

Every shot in this film means something, frames of those images in every single scene deserve to be hung on walls, every moment has a power brought to it by Lynch and cinematographer Frederick Elmes that makes almost anything completely haunting, the most off kilter looks at someone’s face become surprising for reasons that are unknown, the most offhand cuts have an indescribably unnerving effect, how the ever-present sound work makes even the smallest things seem ominous, or just something random in the corner of the frame. Whether it’s Dorothy leaning back in ecstasy, everyone lined up in Ben’s apartment, the darkness of Dorothy’s hallway stretching out, all a part of this look at a small town in the service of this version of the time when some people thought American was something it isn’t now. Every look at someone seems to mean something more in particular when Lynch, just as he does in a few other films, gives us close-ups on someone that are almost uncomfortably intimate, in a way that no other director can pull off, and it somehow makes them more hauntingly beautiful than ever. There’s one brief close-up of Laura Dern like this when Jeffrey leaves for the apartment but also so many of Isabella Rossellini, so powerful that maybe they’re what the male gaze is really supposed to be in all its best ways, appropriate for a director who gives us female characters the way he does, accompanied by rumblings in the Alan Splet sound design that come from nowhere making the most beautiful image unnerving in itself just as the music by Angelo Badalamenti and his score gives the movie a soul, whether haunting or angelic, that is almost unexplainable.

The wind blowing in the curtains, resembling Dorothy’s blue velvet robe, makes us feel uneasy for reasons we can’t even express just as so many things in the film do and maybe to fully understand BLUE VELVET you would have to understand why Jeffrey wants to sneak into that apartment and hide in the closet to begin with. That place where he discovers Frank Booth, a nightmare who has come to life, an id, a demon and one who can only come alive in the dark, taking his neighbor out for a joyride. “This is it,” Frank says before a neon sign in the window reading exactly that is seen, one of my favorite offhand laughs in the entire film, and we can only imagine what his relationship with Ben is just as we can imagine the two of them going way back just as we can imagine Hopper and Stockwell knowing each other in Hollywood way back in the ‘50s only adds to this. No moment during the stopover at Ben’s feels in any way rational, just as it feels like the voice responsible for “In Dreams” can only come from the person who appears to be singing it even as we know it’s really Roy Orbison but it still feels possible right up until the spell is suddenly broken. Trapped in this place, it’s easy to believe that the worst can really happen. There’s no way to escape except to continue into the night with Frank and the jump cut removing them all from the frame on his laugh is just as terrifying as that thought. Maybe we all contain this darkness. If someone says they don’t, they’re probably lying. If someone says they don’t, maybe they have it more than anyone. “Now it’s dark,” Frank says so he can come alive. He lives in an industrial area that feels like the literal bowels of the town and even if he is briefly seen during the day, it’s impossible to imagine him or any of these people ever existing before nightfall. There’s so much plot stuff that the movie wisely skips over since we don’t need to hear it and Dorothy’s silent reaction to seeing her son during the “In Dreams” sequence makes it seem like Frank’s entire plan is simply to do the worst thing imaginable, causing a son to no longer love his mother. That’s where the real darkness is. “You’re like me,” which is maybe the most terrifying thing Frank says of all, as if suddenly realizing what Jeffrey is really doing there.

In some ways what the film does is a dry run for what became TWIN PEAKS, a comparison that was obvious when the show premiered and it was easy to imagine Jeffrey Beaumont becoming Dale Cooper, but it’s also a dry run for a lot of things including what kind of filmmaker Lynch was really going to be as the years went on, with the very idea of story mattering less in relation to what he wanted to explore in his art, an idea still developing here even as it feels totally crystalized. The running time of almost exactly two hours gives the impression there was a contractual element to keeping it at such a length but the film is so brilliantly paced and structured that there’s not a moment I would lose. The extensive deleted footage that has appeared on Blu-ray was a revelatory discovery when it first turned up, running about an hour long (the first rough cut was reportedly just under four hours), but as fascinating and as valuable as it all is there’s not a single moment that feels like it should go back in. The film that BLUE VELVET became as it was molded into that two-hour running time, one of the best such jobs ever with editor Dwayne Dunham presumably working closely with Lynch, turned it into exactly what it needed to be.

Even now, even after everything else I’ve discovered in all the years since, it's about as close to a perfect film as I’ve ever seen. The way the story unfolds, the most shocking moments are revealed in a way that lets the viewer find them and understand for themselves what they mean and though it’s also a perfect film to analyze in many ways what the film is also resists doing that since it’s so purely Lynch and what is going on inside his own head so why spoil all the fun. Even after he’s taken on the hellish joyride by Frank, Jeffrey is never really forced to confront all this until the very end when the horror of it all literally shows up in his front yard. On a structural level, when Jeffrey returns to hide in Dorothy’s closet one final time at the end it’s a brilliant way to return to where all this started but it can also be read as symbolic of so many things, a sort of womb to provide a rebirth as a way for him to enter this world that must retreat back to one final time so he can escape. Jeffrey didn’t have to do any of this in the first place, but in the end as he’s faced with the horrific imagery of that tableau of the bodies in Dorothy’s apartment and as the “Love Letters” montage, a love letter coming directly from Frank into the world, brushes past so much plot stuff we don’t need to know, he’s forced. There’s no other way out. In the end the film presents that interesting experience as something he needed to go through, something real which was entirely because of the dreams and desires in his own head. Moving past innocence is inevitable and necessary but it’s always going to be there as a reminder of what the world could be, as it was when we were still children. It’s there in the mirrored perfection of the two families at the end, the fathers and the mothers as well as the two children who are now together as a reminder of this. The robin with the bug in its mouth seen at the end and the strange world it wants to be a part of. Nothing about it seems real but anything from the past we grew up in long ago can be as real in our memories as we want.

Kyle MacLachlan, fully entering the David Lynch universe after his beginnings in DUNE, displays total confidence as Jeffrey showing him as curious and antsy, frightened and determined to enter this world. He’s an everyman eager for things to happen, with a look that makes it seem like he wants to be cooler than this small town drinking his Heineken, and he gets you to believe that he would really attempt to do all this. He carries the film and grounds it, becoming a perfect fusion with Lynch’s view of the world. And the way the phenomenal Laura Dern takes a character who is supposed to be the normal, dull one and gives her passionate life, bringing a level-headed focus that combines rationality and belief in the good. Because of this film and their other work with him, MacLachlan and Dern are like the avatars for the perfect Lynch couple, how he sees all the good in the world. They are the light.

But so much of the talk of the idea of performance here goes beyond simple acting, particularly the way Isabella Rossellini plays Dorothy as haunted and otherworldly, the way she uses her body language, the way she leans forward and reveals her innermost thoughts just by a glance, always compelling, continually fascinating. When Dennis Hopper enters the film for the first time it becomes something else entirely just from the sound of his voice so where he takes this role becomes a place that feels truly demonic even when he suddenly quiets down and no other Hopper performance ever feels truly this dangerous as if the film itself didn’t know he would go this far. Once he’s there, the unexplainable shift that occurs when Dean Stockwell enters makes perfect sense and he clearly belongs near the top of the list of best one-scene performances of all time. Every performance here is a part of such a feeling, no matter how brief. Jack Nance, for the way he tells Jeffrey his name, and Brad Dourif are perfect just as Hope Lange and Priscilla Pointer are in their worlds as well, in each case you know who they are and what they represent immediately. As Detective Williams, George Dickerson underplays his role in just the right way and finds his cinematic immortality in the way he says, “Yes. That’s a human ear, all right.” It’s a steady presence and the sort of thing needed to believe that there might be someone willing to take charge, no matter what’s going on below the surface.

Just like films, memories fade. Some of them stay with you too and they’re not always the things you want to remember. I was lucky. I don’t usually think of my teenage years that way, there was too much to be depressed about a lot of the time and too much to want to escape, but it’s probably true. There was just a lot I had yet to learn. Seeing BLUE VELVET when it first opened all those years ago meant that it gave me plenty of time to think about what the film was, what it meant, plus I got to see it when it was an audience of people going to see the latest critically acclaimed art film, so they weren’t going to approach it with ironic laughter. Nobody told them that’s what people would eventually do, which is what it seems like I hear about every time the film plays in a theater somewhere and I’d rather not find out for myself. Maybe it’s my problem or at least the way my brain is wired so I never think of this film as merely camp and doing that just always seems wrong. Years after I first saw the film, there was the occasional Lynch Encounter around town from afar. A surprise appearance with Laura Dern after a screening of WILD AT HEART hosted by Edgar Wright at the New Beverly, certainly one of the greatest nights ever at that theater. Spotting him at Figaro on Vermont having dinner. Then one day some years back I was walking down Hillhurst, glanced across the street at some people walking into an ice cream shop and realized that one of them was absolutely David Lynch. I crossed the street, went inside and stood behind Lynch with his family as they ordered then got a chocolate cone for myself, thinking about how I had recently seen a 35mm print of DUNE but of course I didn’t say anything to him. I left them alone. And now David Lynch is buried at Hollywood Forever so of course as soon as that news was announced I went over to pay my respects and sit there for a few minutes. I’m sure I’ll stop by again soon. But so much is in the past and it continues to reach out to us. It should never be where we live today but it does help to hold onto that feeling, to remember that these things did happen. These films were made and still mean something to what we became. It's a strange world and it always will be. In the end, try to find love where you can. Find your way out of the darkness.

Thursday, June 5, 2025

Better Than Nothing

There’s only so much to be gained from spending a lot of time thinking about the past, but this attitude can be a problem when writing about movies released long ago. For one thing, Steven Soderbergh is a director who seems to have very clear feelings about each of his films and how they’ve turned out. Based on multiple interviews with him, he seems to have a firm handle on what he’s tried to do throughout his career and is aware of which films may have gone astray for whatever reason. You get the feeling that he’s perfectly happy to talk about these things, but he doesn’t continually obsess over them either. His mind has been made up. The films he’s made recently have all the confidence of a director who has nothing left to prove while still wanting to try new things but is maybe more interested in just enjoying himself. The shipboard drama LET THEM ALL TALK and Covid-era thriller KIMI feel like they’re among the best of this recent batch, two films with very different goals and the only real criticism I have of them is how much they’ve been allowed to basically disappear into streaming unless you know where to look—presumably they’re still where they’re supposed to be, but who can remember these things. Looking over his filmography, there are a few projects I still need to get to, especially some TV stuff, but it gets easy to lose track when streaming is part of it all. His career seems divided into multiple stages now—the acclaim at the start and the fallout, the rebuilding that led to his Oscar, the studio heights of the OCEAN’S series and the George Clooney partnership, the move into digital, his own rumblings on possible retirement and the return from that decision leading into the streaming era. There is a thread that can be found in each of these and it’s almost like by this point I can recognize a scene directed by Steven Soderbergh just by the font usage and naturalism of the room tone but his films also have that controlled sense of genre and the way they present people trying to understand just who can really be trusted, a theme which turns up in a number of his films as he explores the basic idea from all sorts of different angles.

But to use the example of one film in particular, the director has also somewhat famously been dismissive of THE UNDERNEATH, his remake of the noir classic CRISS CROSS, saying that he decided the film was basically DOA in the middle of production even though he had no choice but to proceed forward. Released in the spring of 1995 (Happy 30th!) to a mixed response and little box office, the experience caused Soderbergh to immediately regroup so he could put together what became SCHIZOPOLIS, a no-budget piece of absurdism that he also starred in. Getting his mojo back from that experience led to the run of OUT OF SIGHT, THE LIMEY, ERIN BROCKOVICH, his Best Director Oscar for TRAFFIC and beyond. And much as I like each of these films, I would still willingly tell him that I also like THE UNDERNEATH, really I do, and would do this knowing he’d never agree but the movie still offers a mix of personal style and suspense that remains effective in a way that still feels like it could only have come from him. I can understand feeling that it’s too sleepy, too constrictive, but as a noir story crossed with the aimless mood in the air of what I remember from the mid-90s something about it still clicks for me, the awareness of fucking up in the past which leads to the realization that the only thing left to do is fuck up again. Coming from someone who still worries about doing that sort of thing, it does make a lot of sense. And it even anticipates films by the director he had yet to make so however he feels, it goes perfectly with his body of work that was still to come.

Several years after fleeing Austin due to gambling debts, Michael Chambers (Peter Gallagher) returns to see his mother (Anjanette Comer) and be there for her new marriage to Ed (Paul Dooley), a friendly sort who works for an armored car company where he soon gets Michael a job. Michael’s brother David (Adam Trese) is openly hostile to him but even worse is when he tracks down his ex-wife Rachel (Allison Elliott) who he left behind and is now attached to Tommy (William Fichtner), a nightclub owner with some criminal activity on the side. Michael goes after Rachel again but when they’re caught by Tommy, Michael offers him a plan to rob one of the armored cars, figuring this will be exactly what he needs.

Writing the script for SEX, LIES AND VIDEOTAPE which became his breakthrough along with how he starred in SCHIZOPOLIS with ex-wife Betsy Brantley soon after their marriage ended makes the films directed by Steven Soderbergh sound more personal than maybe the majority of them are, films that maybe explore similar ideas in a way that isn’t always apparent when the focus feels more on genre. THE UNDERNEATH is officially based on the novel “Criss Cross” by Don Tracy but still feels like it’s returning to themes explored in the earlier film, the idea of a man who screwed up big time returning to a place he once knew to sort out what was left behind. And though he wrote the script for THE UNDERNEATH, Writers Guild arbitration dictated sharing the co-screenwriting credit with Daniel Fuchs, screenwriter on the original film of CRISS CROSS back in 1949, which led to Soderbergh ultimately using the pseudonym “Sam Lowry”. It’s a name many will recognize as the main character in BRAZIL, likely a comment on the bureaucracy involved with the decision and that winds up feeling about as personal as anything else in the film. But there is more to THE UNDERNEATH which delivers a very controlled tone all the way through mixing character study in the heist plotline along with the Austin vibe in the air so at the time it felt like the film was nailing something of the feel of the time. It still does even now, at least in the club scenes or maybe the cool indie tone to it all just feels like the time in general but it’s a meshing together of genre and character drama looking to find a personal connection in the material. SEX, LIES AND VIDEOTAPE opens with shots of a road taken from a car in motion and THE UNDERNEATH begins with its main character driving as well, but in the first film it feels all about possibilities while in this one, a film where the very first moment starts its non-linear narrative structure already in the middle before going back, the route has already been planned but the endpoint isn’t leading anywhere good.

And THE UNDERNEATH does feel personal, not just as partly a fatalistic neo-noir redo of SEX, LIES AND VIDEOTAPE in addition to the film it’s an actual remake of but it also anticipates the setup of his own OCEAN’S ELEVEN remake six years later, a film made with much more of a commercial goal in mind but still a heist movie which is ultimately about getting an ex-wife back more than the job in question, the personal crossed with the interest in genre, an issue of motivation that THE UNDERNEATH chooses to be a little murkier about. The obliqueness of the plotting is a big part of it, like how Michael and Rachel were apparently married but if it wasn’t for the presence of a wedding ring we’d never know, not to mention just the simple idea of motivation as well as just who is playing who at any point. If I’m counting right Soderbergh has directed four official remakes in his career, not including a few others that he wrote or produced, and it almost gives the impression of trying to recreate films he has encountered with his own goals in mind, whether this is all coincidence or his own version of auteurism as criticism. But it’s really a film with a focus on one character and his connection to the people close to him, the guilt that comes with that and the easy ways to screw up all those second chances, mixed in with a welcome number of small laughs coming from the clever dialogue for what mostly feels like a quiet, morose film while always aided by the moody Cliff Martinez score. Something about the approach even feels like the nineties or at least my memory of the nineties or maybe it’s the dream of those nineties films when they played in art houses back then, felt in the nightclub scenes which have the vibe of all those people in the moment responding to the music, those days when you don’t know where you’re going, don’t know why you’re there, don’t know why you’re calling someone, with much less to worry about than you realize until you create all those problems for yourself.

In that noir tradition, it’s also a film about refusing to let go of things that you’ve already run away from, trying to move forward but still holding onto what you once had. “I don’t know if getting back with you is a moment of strength or a moment of weakness,” Rachel tells him, unable to decide. Gallagher exudes a sort of cocky intelligence as Michael but one that’s always looking for a short cut, seen reading multiple self-help books in search of the magic answer. But nobody has that answer and no one can let go of those resentments of the past or the dream of that big lottery win which you keep telling yourself is going to come eventually and it really is a film populated by people looking for the winning lottery ticket so they can get that easy money, particularly in the flashbacks of Michael gambling and buying a huge, stupid satellite dish to watch all the games he’s betting on. Rachel is looking to be an actress in the flashbacks, or maybe just the winning lottery ticket of being an actress, but the only big audition we see her preparing for is to be the girl who hosts the nightly number pick. Even Michael’s mother wants her lottery scratch-offs as her wedding day approaches, just in case that big win could still happen. The most decent person in the entire film has the healthiest attitude about the way things turn out in life and even his own big dream is still a modest one. Maybe the second most decent person in the entire film also has a regular job and is smart enough to know that she’s the girl in second place but that’s the way things go sometimes. In the noir tradition, the film really is about wanting more which is always the easiest way to screw things up.

The tone through it all is set by how careful the direction always is down to the framing of every single shot which at least partly seems to be what Soderbergh disliked in his own film the most, looking to ultimately break free from all the constrictions. This is all filtered through his visual and storytelling tricks via a non-linear narrative that jumps from the present tense to flashbacks and flashforwards that detail Michael’s movements on the day of the robbery all done in a way that, helped by film stock and the presence of a beard, feels so assured that it never becomes confusing. If Robert Siodmak’s visual style in CRISS CROSS is a product of German expressionism, then what Soderbergh does here is more like American indie Expressionism, at least it felt that way until PULP FICTION changed everything about how to approach crime dramas then, but here it’s at least doing something with the frame that keeps it always active through a cutting style equally careful about keeping your focus on what’s right there. It’s a reminder of how much of this purely visual approach was still possible when all this was being done on film, not that I want to turn this into a film vs. digital debate, but something really was lost when Soderbergh abandoned the former for the latter and his aesthetic was altered which he seems ok with anyway. But the look he achieved back in the ‘90s is stunning and it’s a gorgeous looking film, shot by Eliot Davis who would do the same on OUT OF SIGHT a few years later, and it almost feels like part of the point of the whole thing was to make it gorgeous looking even if this look became something that kept it distancing. It’s a visual style that pushes the use of colors and the anamorphic frame all through, to make every single image stand out if it can, with enough split diopter shots all through that it feels like Soderbergh was having fun making this film, I just have to take him on his word that he wasn’t. But that kind of framing does give certain moments the classic De Palma feel, along with the diopter-heavy look to an early dinner table conversation that I’m guessing took its inspiration from the framing of the mashed potato scene in Spielberg’s CLOSE ENCOUNTERS. Even a vendor number spotted in giant close-up that figures into the plot is likely an obvious George Lucas reference. And the way the film basically stops dead, in a very effective way, in the aftermath of the big heist with the multiple timelines finally converging during the final third with part of it directly from Michael’s queasy POV which offers no escape, a destination that can only be a dead end with nowhere else to go.

But along with all this is that feeling of a low hum through the entire thing which plays as correctly noir for the nineties, a very different era than the post-war heyday of the genre but people are still trying to find the easiest way to get the payout. “So beneath the apathetic exterior there was actually a raging indifference,” Rachel says to Michael about his behavior which is one way to look at character motivation and the tone of the entire film as well. The harshness of the dialogue that veers into jokiness since people like this are going to make those jokes anyway. “You’re not very present tense,” Michael is also told and the non-linear plotting feels appropriate for a main character who is so unmoored, along with how so much of the film seems to be in the desperation seen in the eyes of various characters who can’t seem to smile unless they know how to fake it. Fittingly, it’s a film with a main character who’s never as cool as he thinks he is, not when he’s placing his bets, not when he’s trying to get Rachel’s attention via cocktail napkin placed under a drink and certainly not when he comes up with the entire stupid plan to begin with. It also feels cynical enough that what happens to the main character barely seems to matter at the end and you could hardly blame someone for not even remembering when he’s last seen since the final moment since the film shortly after moves on to someone else shortly after and then the very end raises a few other questions entirely. The similarities to OCEAN’S ELEVEN are there—we still need to keep straight exactly what is a remake of what here—but to compare the two it’s like with THE UNDERNEATH he was making a mood piece/character study/art film and with OCEAN’S, along with its sequels and a few others he’s made, he wanted to make a movie and that’s where the fun of these things comes from. Maybe it was also the chance to do something like this over again and not only make it more commercial but more human, not so ice cold and fatalistic. It’s a fantasy version of trying to do that sort of thing over to make everything right and the OCEAN’S films certainly have nothing to do with reality but maybe he decided that type of escape is one of the reasons we go to the movies in the first place. With THE UNDERNEATH and its combination of character study of a fuckup and noir thriller to explore how well the genres can mesh it still works and feels like a movie about the possibilities always in front of us, it all just gets screwed up when we can’t get out of our own way. When it comes to these things, there’s no point in going back. You’ll just be fucked over again. Whether it’s by yourself or the person you went back for, it doesn’t make any difference.

Maybe part of it is that overall sense of coolness from the performances which they need to be, where every single smile in the film could be like someone putting on an act. Peter Gallagher (seen recently playing a future version of John Mulaney on his Netflix talk show) lets his eyes do a lot of the work to go with the steadiness in his voice, a man trying to stay focused and convinced that the next bet will finally pay off with Alison Elliott who brings a harsh cool girl vibe to someone keeping her distance from everyone else no matter how close they want to think she is to them. William Fichtner plays the live wire, ready to snap at any moment and he even gets a nervous laugh at one point out of the tiniest head nod. The effectiveness of the supporting cast adds the humanity that isn’t felt as much from the leads including Paul Dooley who is just as warm and welcoming as you want him to be, the total resentment that comes off Adam Trese as the brother, the way Anjanette Comer as the mother always seems to be holding back what she’s really thinking and Joe Chrest as the mysterious Mr. Rodman in the hospital. Elisabeth Shue, months before her Oscar-nominated role in LEAVING LAS VEGAS was seen, is ideally cast as an also-ran girl who we can’t imagine why Michael doesn’t go with her since she seems so right, sensible and charming but never dull. This should be the girl. But that’s not the film the main character chooses to be in. Harry Goaz of TWIN PEAKS is one of the other drivers at the armored truck company, Mike Malone who featured prominently in SCHIZOPOLIS is seen hitting on Alison Elliott, Richard Linklater is the doorman at the club and Shelley Duvall, one of two Altman alums in this along with Dooley, is the nurse in the hospital in a scene which likely took no more than a day to film. There’s also the recently departed Joe Don Baker, RIP, wearing a bolo tie in a key role as the boss at the armored car company that isn’t much more than an extended cameo but his few moments onscreen do give us his cagey presence and smile, reassuring us more than anyone else does which in this film of course means there’s no reason to trust him. I like Baker here more than I like the way his final scene raises more questions than it answers but right now it’s just nice to see him get the very last moment in a film like this. After all, Joe Don Baker getting the last moment in a film is sometimes what cinema is all about.

“Anything’s better than nothing,” Michael says as a reason for doing anything with anybody. It’s one thing to tell yourself when you don’t have any other ideas and that speaks to the malaise felt when there are no better ideas. Looking for more thoughts on the film from Soderbergh, I picked up my copy of “Getting Away With It”, his book consisting of half interviews with Richard Lester/half diary of his activities around 1996, leading up to the beginnings of his involvement with OUT OF SIGHT, only to discover that he barely mentions THE UNDERNEATH at all aside from his horror at having to sit through it at a festival screening in France. It seems obvious that he had already moved on from the film by that point and there wasn’t even anything to say about it anymore. We should all have such a strong work ethic. One of the ways to see the movie has been its inclusion on the Criterion Blu-ray of his 1993 film KING OF THE HILL, which he thinks a little more highly of, making THE UNDERNEATH a literal B-side although the film by itself has since gotten a non-Criterion release on Blu as well. Thinking about all this makes me think about my few brief encounters with Soderbergh through the years one of which was a brief conversation with him at CNN when he was promoting KAFKA but it hasn’t happened anywhere since standing in the popcorn line behind him at the Chinese on opening weekend of THE DEPARTED. All this is in the past, of course. If I ever meet him again, I have a couple of very geeky OCEAN’S questions about those films which I hope he would have the good humor to answer. As of this writing, he’s had two films released in 2025, the horror film PRESENCE (I’ll see it, I swear) and BLACK BAG (minor and enjoyable) with another in the can still to come. As for THE UNDERNEATH, returning to the film again now reminds me of back then, it reminds me of the mistakes I made, it reminds me of the mistakes I could make. But if it’s up to me then I’ll just choose not to live in the sort of noir film that will just lead to more wrong choices. It’s still possible. It’s always possible to change things if you feel that strongly about the direction you’re heading in. Even if you’ve made a film that I’ll be willing to defend as much as THE UNDERNEATH.

Wednesday, May 7, 2025

It Doesn't Know The Words

There are times when nothing is as important in a film as the person in the frame. Some might disagree. Some might say that a film needs epic scale, giant action scenes or big special effects. But sometimes all that matters can be a scene about two people facing off against each other, every shot of someone’s face giving us another chance to study what is going on inside of them, revealing something unknown about who they are and what they want. The chance to study a face can result in imagery that feels more purely cinematic than anything else imaginable. Some directors, maybe the very best directors, understand this. To use a non-film example, it isn’t a stretch to call THE LARRY SANDERS SHOW, now and forever a blisteringly funny look behind the scenes of a late-night talk show, one of the best TV shows of all time while also being one of the most no frills. The sets are simple, the way scenes are shot is simple as it moves between the film look for the office scenes and video for the show, even the credits are simple. All that matters is the continued desperation of the people in the frame with star Garry Shandling and the other regulars continually doing brilliant, fearless work delving further into the depths of their character’s bitter neuroses even as the plastic smile remains frozen on Larry’s face whenever the camera is on. Running for six seasons on HBO in the ‘90s, the show even looks borderline cheap much of the time, but it was so consistently good that this never mattered and my complete DVD box set will always be close by. SANDERS is mostly remembered now by people who were there back then, fully attuned to the look at the showbiz world it was displaying with the bitterness and insecurity found in the characterizations that remain completely authentic even as the world it’s set in now feels mostly archaic, a memory of a Hollywood that doesn’t quite exist in this way anymore. In comparison, WHAT PLANET ARE YOU FROM?, the one Garry Shandling movie vehicle ever made, directed by Mike Nichols and released in March 2000 less than two years after the finale of LARRY SANDERS, is totally forgotten now. The only way it seems to be remembered is through the pages that cover it in the extraordinary biography of Nichols written by Mark Harris which describe in detail what a disaster the production was, how much the director and star clashed and that there was nothing to do about this once filming was underway.

For Mike Nichols, this film came off a run of big movie star vehicles in the ‘90s which included the well-regarded POSTCARDS FROM THE EDGE, the not as well-regarded REGARDING HENRY, the very expensive WOLF, the smash hit THE BIRDCAGE plus the somewhat forgotten film version of PRIMARY COLORS, a run that is of varying quality but the films all have an air of respectability. In this context, everything about WHAT PLANET ARE YOU FROM? feels like it’s intentionally disreputable in comparison, a silly sex comedy focused on the eternal conflict between men and women so you wonder just what attracted him to the material beyond an initial interest in Shandling, although it does mark the second time he directed a film with a question mark in the title in case you ever want to play this on a double bill with WHO’S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF? Which doesn’t sound like a bad idea, come to think of it. The film also cost much more than THE LARRY SANDERS SHOW ever did and it feels like more of an oddity now than the trainwreck its reputation indicates but it also feels like a very expensive oddity, much more than it needs to be. In truth, the film actually does make me laugh enough that it’s the sort which makes me look around carefully before whispering, “I actually kind of like that movie,” even as I know that it doesn’t quite gel, a film with a sense that it has something to say but never finds a consistent tone that a film, any film, should have. There are laughs and it also contains a degree of intelligence, along with the growing awareness that it's trying to explore a particular aspect of what develops in a relationship between a man and a woman but this is mixed in with humor that seems to go all over the place. The result can’t be called uninteresting but it’s possible the things about it which seem the most intriguing weren’t what the makers hoped anyone would focus on, even if it does possess a certain unique comic tone. In one SANDERS episode, Larry waves at an offscreen Mike Ovitz in a restaurant while saying, “He could get me a movie.” “Do you want a movie?” his companion wonders. “No, but it would be nice to be asked,” he replies. Anyway, this is the movie.

On a distant planet populated solely by genetically created men, one of them is assigned by the planet’s leader Graydon (Ben Kingsley) to travel to earth with the intent to impregnate a woman then bring the baby back to the planet to begin repopulation and eventually take over the universe. In the guise of an earthling named Harold Anderson (Garry Shandling) he arrives in Phoenix to take a job in charge of commercial and home loans at a bank to find a woman although the loud humming noise the penis that was attached to him makes when aroused proves to make this difficult. After being shown around town by co-worker Perry (Greg Kinnear) who is always looking to cheat on his wife Helen Linday Fiorentino), Harold soon meets recovering alcoholic Susan Hart (Annette Bening) who shows an interest but insists that she won’t sleep with anyone until she gets married which Harold quickly agrees to and quickly starts working to get her pregnant as fast as possible. Meanwhile, FAA investigator Roland Jones (John Goodman) is looking into the strange occurrence on the plane when Harold first arrived and begins closing in on him.

WHAT PLANET ARE YOU FROM? is basically a dick joke, but one that’s in the guise of being a more introspective, satirical look at how men see themselves in the world and what can get them to finally settle down and try to understand women, who don’t always have the best answers either. But it’s still a dick joke, specifically a running dick joke involving the loud humming noise made by Harold’s penis that has been installed on his alien body and for a conceit that so much of the film is based around the joke never becomes as funny as the movie wants it to be, not at first and not every other time it happens. The very idea of the R-rated comedy aimed at adults is not a new concept for Mike Nichols but this never seems like enough of an idea to base so much it around, as if the concept of the film came out of awareness of the 90s bestseller “Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus”, then asking what if the two sexes really were from different planets and how that would affect things, figuring out a way to fit all this around the basic Shandling character in a way that Albert Brooks did with his films. It’s not a bad idea plus the character he created and played on THE LARRY SANDERS SHOW certainly made it seem like he could carry a film but the problem is that that it never feels clear if this is meant to be a goof or a real movie, an actual performance or a stand-up routine, maybe a reminder of what Jerry Seinfeld, knowing what he was good at, never tried doing when his own show ended.

There is a definite intelligence to the humor in the script (story by Garry Shandling & Michael Leeson, screenplay by Shandling & Leeson and Ed Solomon and Peter Tolan) particularly in the specifics of tiny interactions like the way Harold has been instructed to always reply “Uh huh” when a woman is talking so there are comic moments that connect but the tone never seems fully decided on, just that it wants to get some serious ideas across in the silliest way possible. No married couple in the film is happy, practically the first person who Harold meets when he arrives is a woman who just had a fight with her husband and even the couples being shown houses by real estate agent Susan are always seen fighting. It’s always about conflict and deception when men and women are involved, like one scene involving four people where three of them know all too well that the fourth is lying to his wife and it feels like there’s a concept somewhere in all this but it never quite balances the two halves, the ideas haven’t all been correctly organized for the points to be made.

Part of this has to do with approach and if the film had been designed with a more stylized low-budget look along the lines of BEING JOHN MALKOVICH or even the somewhat grounded afterlife of Albert Brooks’ DEFENDING YOUR LIFE that might have helped but the film never feels like it’s being made by someone who has interesting ideas for shooting any of this this outside of a focus on the giant special effects throughout when he feels the scene calls for it. The effects aren’t badly done at all, they just don’t matter and there’s still plenty of them throughout involving the distant planet and arriving on earth via transporting to an airplane but that’s not what the movie’s about, or at least it’s not what it should be about, and the humor of the script makes it all feel unnecessary. There’s a fair amount of effects work in some of Nichols’ other ‘90s films particularly WOLF as well as the opening shot of THE BIRDCAGE which began with an extensive helicopter shot that eventually went right into the nightclub of the title so it almost feels like he’d gotten so used to making films that were this expensive he never stopped to think if making it so elaborate was absolutely necessary to what the film needed to be instead of paying attention to the words. It’s a film that would have been helped by being smaller and quirkier so the ideas that feel important get overwhelmed by the scale, as if simply there to give Columbia Pictures another big budget MEN IN BLACK-type sci-fi comedy and the emphasis on the wrong things feels like a misunderstanding of the material.

The approach to the comedy wants to be more hopeful than the outright misanthropic feel of LARRY SANDERS while still at least attempting to be about character much of the time and, leaving out that he’s an alien, showing a man who has nothing to worry about but his overly active penis, meeting a woman desperately looking for stability in her life who grabs onto the most unstable relationship imaginable. And even without trying, he helps her see what’s out there and brings instant clarity to things more than any other way she’s tried to do it while she gets him to find a level of humanity that he never even considered might be there. All of this is fine and breaking down the plot helps to see it as a satirical look at a man understanding what he should be in the world and what he should care about. In some ways, the premise could even be the idea for an extended Nichols-May sketch but that’s not the personality of the writing so since the project originated with Shandling and writers connected to him, bringing in Elaine May for a polish likely wasn’t going to happen but it wouldn’t have been a bad idea.

Either way, it’s about a man and a woman getting to know each other but needing to get past whatever the sex is to that relationship at first and maybe I’m really digging to find stuff in here but the arguments they have are at least more interesting than the film playing Lionel Richie’s “All Night Long” over shots of the Bellagio Fountain in Vegas during the honeymoon sex marathon. The sequence does give us Susan saying, “We even did it while we ate. If I’d known we were going to do that, I wouldn’t have ordered the soup” which is one of the better lines and the script does find some truth in the sort of arguments that happen when you’re starting to wonder just who the person you’re suddenly in a relationship with really is. The ideas are in there but too many of them are muddled and at times there’s the feeling that Nichols is more interested in finding those performances than where the laughs are going to come from which means that some of the humor, like Harold getting more consumed by his job than he expected and the head of the planet getting more exasperated when he complains about all his marriage issues, doesn’t feel fully developed so it simply comes off as random. And there’s still the issue of how much of all this should be a joke, how much of it should be taken seriously as a movie plot. Even the most visually interesting element of the film, the mid-century modernistic vibe of the Phoenix Financial Center location where the bank is set, feels incidental but it does give the movie a certain retro feel so it seems like the version of this that might have been made in the sixties when they might have set it in Phoenix because the production didn’t want to go too far from L.A. Along with the location work and interiors set in Phoenix that emphasize the ‘southwest’ aspect there’s also the sets on the alien homeworld which are stark but not particularly memorable and also seem more elaborate than the film ever needs.

It's been twenty-five years since this film was released and one unexpected thing that jumps out about it now is how it’s about a planet of sexless men—incels, to use the current parlance of our time—with a main character forced to interact with women and is totally baffled by them, no idea what the relationship is supposed to be once the sex is taken care of so he resorts to watching whatever game is on and telling her, “Maybe I haven’t touched you as much as I used to but that’s no reason to destroy the remote” is the natural endpoint to that. A version made in 2025 exploring the same basic idea would probably be much darker, more hostile and maybe not much of a romantic comedy but in this film the problem isn’t anger, it’s not having the slightest idea how the communication is supposed to work, just interested in sex or something else entirely and the main character has no idea how to take any responsibility with the baby he’s been so insistent on having. The best moments bring out the laughs in this, but too much doesn’t seem fully thought out and too much effort seems put into the mechanics of the third act return to the alien planet for plot and chases along with a Carter Burwell score that works harder than it should need to. When things are resolved it’s quick and almost absurdist, which in a smaller film would get the right sort of laughs but here it winds up feeling like it’s not always clear if the serious moments matter as much as the comic ones or if it’s all just meant to be a big goof.

There’s still enough cleverness to the dialogue and interactions along with how Mike Nichols knows that the scenes which really matter are the ones with the two lead characters trying to understand each other, in a film about how the goal is not so much to understand each other but to come to the realization that you’re both confused about it all and some kind of genuine understanding can come out of that almost without even realizing it. When Bening emerges to sing “High Hopes” to Shandling before breaking the big news of her pregnancy it’s an amazing moment and maybe the best in the entire film, all the happiness and terror and desperation felt in this woman, hoping that all will be right in this very strange relationship she’s suddenly found herself in and all of this has nothing to do with aliens or special effects or even at attempt at making a joke. Just the sort of character interaction that the people involved could excel in at their very best. In that moment is an idea for a movie. And it’s at least something.

The thing is that it’s like Garry Shandling and the film itself doesn’t seem to know if he should play this as an actual performance or as a Jack Benny-type (or, more specifically, Shandling himself on his earlier IT’S GARRY SHANDLING’S SHOW) starring in his own film as his own basic character and it never becomes either. The emotional moments he needs to play in close-up don’t feel earned and a few comical asides wind up feeling like they come from a Shandling adlib more than the character so it doesn’t connect, no matter how much his very presence can easily get a smile out of me. On THE LARRY SANDERS SHOW he was a person with no idea how to connect with someone when he wasn’t on television and here he’s a person (or alien) trying to do figure out how to do the opposite but he doesn’t have the acting muscles for that. Just about his best moment comes at the very end when he says something dismissive about Susan’s friends and the bickering between the two of them comes off as totally natural, unlike all the moments searching for emotion when you can feel the effort. The issue with Shandling onscreen makes me wonder who else was around in those days that might have been a better fit even if it was designed as a vehicle for him but considering who the female lead is it suddenly makes me think of Warren Beatty in the role saying these lines and nailing the jokes so now that’s the version I want to see—he was doing TOWN & COUNTRY, also with Shandling, around this time instead. But the grounded nature that Annette Bening brings to her character here helps the film more than it almost seems possible and it’s not at all an exaggeration to say that she gives a legitimately great performance in this film. Even if some of what’s here recalls parts Bening had already played—a real estate agent like in AMERICAN BEAUTY, addressing an AA meeting like in MARS ATTACKS!—what she does brings such a degree of genuine humanity that it becomes a better film more able to focus on the satirical goal and when her character first appears it feels totally genuine almost as if she’s a person I’ve known. I won’t go as far as to say that this is one of Annette Bening’s best films and based on her quotes in the Nichols bio it doesn’t seem like a subject she would want to talk about for very long but I will say that her performance here is one that reminds me how good she really is, how much she holds the drama here together as well as the comedy almost solely by the weight she brings to even the most unexpected moments.

There’s also strong work by the entire supporting cast, sometimes from people who are only in one scene. John Goodman finds the right sort of humor in getting obsessed with this case more than his wife can ever understand and Greg Kinnear brings the needed clean-cut smarm to Perry, Harold’s rival at the bank, playing a man who always looks for every possible way to get out of admitting what he’s really doing. Ben Kingsley earns his paycheck as the leader of the planet, saying ‘penis’ more than a few times and expressing just the right amount of annoyance. Linda Fiorentino, close to her last film to open in theaters (the forgotten WHERE THE MONEY IS, which she stars in with Paul Newman, came out about a month after this) and it still makes me sad how she vanished, nails every broodingly sexy line she has in her few scenes as Perry’s wife Helen. Judy Greer gets several memorable moments as a flight attendant who meets Harold again later on, Richard Jenkins is his boss at the bank, Caroline Aaron (one of the secretaries in WORKING GIRL, along with multiple Woody Allen/Nora Ephron appearances) is also borderline great as Goodman’s wife, an uncredited Jeaneane Garafolo is on the plane when Harold arrives, Stacey Travis is a woman he approaches at the Phoenix airport, Octavia Spencer has a bit part as a nurse and Nora Dunn as one of Susan’s best friends gets what is probably the best line in the film during a restaurant scene, which is something that could easily have been cut but turns out to be just the sort of random laugh the film is looking for in its nitpicky humor but doesn’t always find.

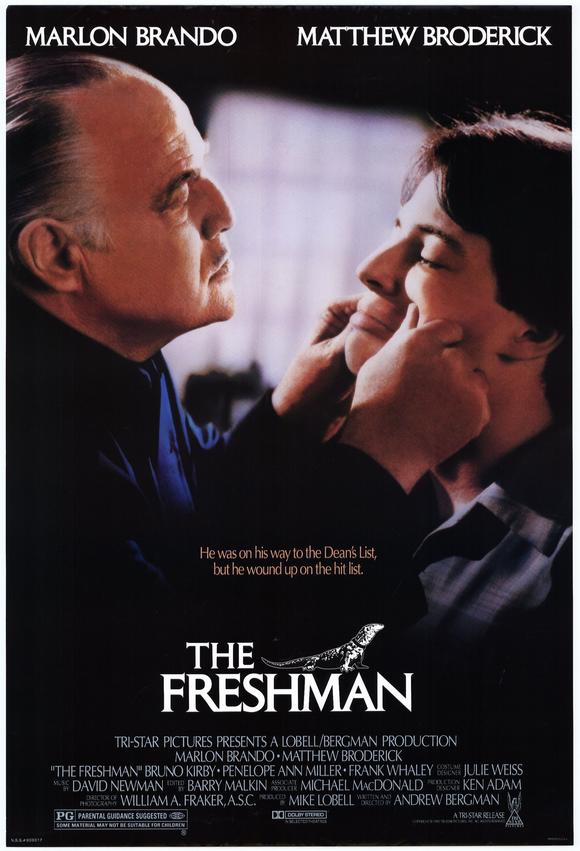

Even if WHAT PLANET ARE YOU FROM? is sometimes called the worst film Mike Nichols ever made, I’ve already expressed some fondness for it so this means I can’t go that far. To mention a few others, the oddball comedy THE FORTUNE feels even more paper thin, THE DAY OF THE DOLPHIN is just perplexing and even BILOXI BLUES, the only Neil Simon adaptation he ever directed and a sizable hit at the time, feels like just a basic filming of that play and not very interesting. More than those films, at least WHAT PLANET offers a deadpan fun to its satire even if it doesn’t always come through. With a reported budget of over $50 million, the film made only $6.2 million in total, possibly less than anything in the year 2000 which opened in as many theaters as this one did. The immediate fallout of the film’s release included Columbia Pictures pulling the plug on OTTOMAN EMPIRE, already announced to be directed by Andrew Bergman and star Keanu Reeves playing a furniture salesman revealed to be a former porn star who catches the attention of the first lady which was set to start shooting soon with Variety speculating that the studio was balking at “another pricey sex comedy”. I still want to see that film. And, of course, WHAT PLANET ARE YOU FROM? did not make its lead actor/co-writer a movie star. But I still love Garry Shandling and miss him. In the very best episodes of THE LARRY SANDERS SHOW, he somehow made the desperation, the insecurity, the self-loathing you feel, whether in Hollywood or not, always relatable. And in those years after this film when he didn’t seem to be doing much of anything at all, it was just nice to know that he was out there. It was a very sad day when news of his passing hit, already nine years ago now, but remembering him helps. Even this film helps me remember and at least this film attempted to say something about the desperation which you can never totally leave behind, no matter what planet you're on.

Tuesday, April 15, 2025

One Of The State

Among the many things these days that remind me how we used to be a proper country, one of them is the realization that Walter Hill films were once a regular thing. We really should be grateful for what we had. At their very best they make up some of the most memorable and unique action films around so while they may not all work and my love for some is stronger than others, I’m still thankful for what we got. It’s a body of work that includes his directorial efforts along with several early memorable screenplays not to mention his close involvement with the ALIEN franchise and so much of it still contains a power in the way they combine his stripped down storytelling techniques with an unabashed comic book style, a harsh kind of pulp that offers both action and edgy comedy in a heavily stylized vein, a mashing up of Howard Hawks and Sam Peckinpah but also a third element which was his own unique point of view. There’s a sincerity always felt in each film which is one of their greatest strengths and Hill doesn’t deconstruct the genre he’s working in so much as construct what he wants an action movie created by him to be. He makes films that have no time for any bullshit. Some might simply call them modern day westerns but there’s more to it than that and the approach is always completely no-nonsense, delivered by a man who doesn’t fuck around with clear-cut plotting crossed with total filmmaking confidence. Not to mention how in plenty of photos showing him directing he’s wearing sunglasses, which always seemed very cool. And these days nothing seems to say as much about his sense of pure storytelling economy like the fact that he’s never directed anything with a running time over two hours. The film begins, makes its statement and he walks away. That’s a Walter Hill film.

The very best of his work displays the beauty found in his no-nonsense yet still stylized approach whether it’s THE DRIVER, THE WARRIORS, THE LONG RIDERS and of course the smash hit that was 48 HRS. which could easily be called one of the most influential movies of the ‘80s. Among some of the others, STREETS OF FIRE may be the most Walter Hill film of all, the purest expression of the way he sees the world, and it’s the one with the devoted following now but speaking as one of the biggest JOHNNY HANDSOME defenders out there I’m still waiting for that cult to emerge. And even if I’ve never been one to make a big case for his lone comedy BREWSTER’S MILLIONS, for example, or maybe LAST MAN STANDING, his western/gangster YOJIMBO/FISTFUL OF DOLLARS hybrid starring Bruce Willis which didn’t work for me much at all even if there are times when I can appreciate the purity revealed in his approach. But 1995’s vastly underappreciated WILD BILL is close to being great and I also remember having a blast seeing his 2002 prison boxing film UNDISPUTED in a nearly empty theater. Then there are those times when his films really do feel like Walter Hill trying to make what he thinks people want from a Walter Hill film, like how the 1988 buddy cop movie RED HEAT is in some ways pure Walter Hill but it doesn’t seem to be anyone’s favorite Walter Hill.

The pieces of RED HEAT are all there and the thing plays but the film never fully catches fire so instead it cruises along, hitting all the beats you expect it to as the bullets fly and bodies crash through windows, with lots of broken glass everywhere. It crosses the basic idea of Don Siegel’s COOGAN’S BLUFF about a cop from elsewhere coming to the big city with what can easily be called an unabashed redo of the basic 48 HRS. formula, going back to the buddy cop setup of clashing personalities in his previous hit which is fine since redoing ideas seemed to work out for Howard Hawks more than a few times. It just feels like the bones of the story are all there in RED HEAT without giving enough of the meat, even though the film tries its best to make it seem like there’s plenty to chew on. Opening in June 1988, just one week after Peter Hyams’ THE PRESIDIO which was another cop film that in the context of summer releases could be called underachieving, this was all roughly a month before the entire formula would be upended by the arrival of DIE HARD, a hit that no one saw coming at this point. Walter Hill wasn’t really the type of director to make the sort of action extravaganza designed to build to the biggest explosion imaginable, but his films still have a certain energy much of the time. RED HEAT does too, at least partly. Of course, if you’re going to rank all the films made by a certain director then something is going to have to fall in the middle. Maybe that’s where RED HEAT lands.

When Moscow police captain Ivan Danko (Arnold Schwarzenegger) goes after mobster Viktor Rostavili (Ed O’Ross) his partner is killed and Viktor flees to the U.S., specifically Chicago, where he is soon arrested on a minor charge. Danko is sent to retrieve Viktor and bring him back, with specific instructions not to let the Americans know the full scope of his crimes. Once there he is met by Chicago police detective Art Riznik (James Belushi) but an attempt to transfer Rostavili to the airport for the flight home results in Riznik’s own partner being killed and Viktor on the run so the two men are soon forced to team up to capture him with Danko determined to keep the Americans from learning the real reason for him tracking Viktor down.

On the surface RED HEAT is the star vehicle it’s meant to be, with lots of continuous action along with a pairing of two disparate personalities designed to clash as they make their way through a plot that is continually attempting to seem busier than it needs to be as if trying to distract the audience from realizing all this has been done before. This is, after all, a film where the partners of both lead characters are killed before the inevitable team-up, not to mention one of them killing the bad guy’s brother, as if the film couldn’t think of anything else bad that might happen to get things going. The plot (story by Hill, screenplay by Harry Kleiner and Hill & Troy Kennedy Martin) hits all the necessary beats but in a way that makes the movie feel like it cruises along as opposed to breaking out from the formula and doing anything even slightly unexpected. The Walter Hill style means no fat and because of this the film never feels like it’s wasting any time, even if the nature of the plotting means it takes a little longer for the two leads to team up than we’d prefer. As much as it’s a part of the buddy cop formula, what sets this one apart is a more grounded, low-key approach to things although whether anyone goes to a movie like this for actual serious issues is debatable.

It’s an ‘80s Walter Hill film with all the expected elements from him—lots of neon, barking police captains, sharp girls, snarky waitresses, a city at night which seems to be all scuzzy hotel rooms and parking garages. The attention-grabbing opening set in a Russian bathhouse filled with naked men weightlifting, plus a few women scattered in there, does feel like a more heightened, comic-strip approach as if part of what now feels like Film Twitter-approved ridiculousness coming from the introduction of an almost-naked Schwarzenegger, panning up his entire body in a moment that seems perfectly designed for the star's reveal leading to a fight in the snow complete with ultra-loud punches to the face. This all builds to the discovery a few scenes later of a stash of cocaine hidden in an artificial leg he breaks off and the film never quite becomes this much fun again, even as the action kicks off so when the plot settles down in Chicago it becomes more about the neo-noirish Walter Hill world, maybe a little scuzzier than usual. Some of this is interesting, with what feels like an endless night focusing on the moodiness and crummy, aimless lives the characters lead, the way Danko doesn’t seem to have much at all beyond his work and pet parakeet he has an alarm set for feeding and the way Riznik’s captain talks about him he’s apparently close to being fired or suspended or something. Neither one of them seems to have anybody of substance in their lives, no girlfriend for either of them to call on the phone and yell at. Even the dancer played by Gina Gershon who has a secret connection to Viktor has her own depressing reasons for getting involved with all this. Peter Boyle’s police captain with an office that has a fish tank and recordings of calming sounds playing seems to have the only idea for how to deal with everything around him but even he suspects it might all be futile. This makes for a grounded, somewhat serious vibe even with the occasional wisecrack with cops going up against the lower classes that can’t get ahead and no one particularly happy about it which makes RED HEAT more interesting than it might have been but not as fun or crazy in a way that might have helped make it truly memorable. The film always seems intent on getting to the necessary action beats but doesn’t seem to spend much time figuring out a way to do something with them that would be genuinely surprising.

For Schwarzenegger, this film comes during that stretch between the release of the first two TERMINATORs where his career was in an interesting place, already a superstar yet not quite in the stratosphere he would reach in the ‘90s where it felt like each of his action films was an attempt to make the biggest movie of its kind ever. Ivan Reitman’s TWINS, the very definition of a formulaic ‘80s comedy, was a big hit at the end of 1988 but it feels like his most rewatchable films during this period are the ones that successfully make the tone of the film as giant as his screen presence, namely the two he did for producer Joel Silver, COMMANDO and PREDATOR, then later in TOTAL RECALL for Paul Verhoeven. John Irvin’s RAW DEAL from 1986 is the one that never got much attention but it doesn’t play all that bad now and is maybe the only Arnold movie during this stretch that, R rating or no, doesn’t feel pitched towards kids at all. RED HEAT falls somewhere in between all this and one of the most interesting things about it is the way it presents him in the frame, first in uniform then later in the blue-green suit that Riznik says makes him look like Gumby. In some ways it’s an alternate, more vulnerable version of his stoicism in the first TERMINATOR, made more interesting when learning how Hill recommended Arnold closely study the Greta Garbo performance in Ernst Lubitsch’s NINOTCHKA where she plays a Soviet officer arriving in the West for the first time, so if Garbo ever had a scene set in a crappy hotel with a coin-operated TV that plays porno, Arnold’s reaction is likely similar to what hers would have been. This makes me wish there were more Lubitsch to the film which allows him to approach the role with a subtlety that he didn’t always get to do elsewhere and the result feels like he’s really playing a character here.

The sequences set in Russia were mostly filmed in Hungary and Austria with some footage actually grabbed in Red Square, the first such Hollywood production to be given permission to do so (“…but why?” asked Leonard Maltin in his star-and-a-half capsule review) and this film happened not too long before the wall came down so looking at it now years later the portrayal of Russia as filled with organized crime does have some added interest and by having the Georgian bad guy Viktor team up with a gang of black militants whose leader is behind bars, the film seems to be drawing a line between the underclasses of the two countries. When Danko is challenged to hold onto steaming hot rock just removed from the first being told, “If you work with steel, you should be used to the heat,” it’s pretty much the first line in the films as if saying right off the bat how this world is divided between the people struggling as much as anyone and those who refuse to acknowledge the differences. Each character in the movie seems to be just trying to get by, up against all the faceless higher ups in charge. Even the most powerful crime lord in the movie is already in jail. There’s no kingpin here, just the Russians trying to keep the influence of America, in the form of the drugs Viktor wants to bring over, from getting there for as long as possible as if fully aware that the end of the USSR is approaching fast which has more to it than the outright cartoon that was ROCKY IV. Even Garbo became seduced by the west in NINOTCHKA, something that never comes close to happening for Ivan Danko.