Among the many titles of the late-70s & early-80s that had certain famous directors going more extravagant with productions, budgets, running times and the overall extremeness of their various approaches, Sidney Lumet’s two-hour-and-forty-seven-minute PRINCE OF THE CITY, released in August 1981, may be the most stripped down of any of them. This is little surprise since considering his dry, non-showy style Lumet doesn’t seem the type to ever go nutso in a Friedkin or Coppola kind of way. That said, while this film may have been an attempt to return to the success he achieved with SERPICO eight years earlier the stylistic approach taken to its length as well as sheer volume of information doled out feels like it was intended to be his most audacious attempt to examine, within his deceptively straightforward visual style, just how much information he could pack into one narrative, how much people could really process. Now, I’m no genius but I’d like to think that I’m not the biggest idiot either and even I couldn’t help but wish the movie had been maybe slightly more user friendly if only to allow a person seeing it for the first time—like me, I guess—a chance to get their bearings in the beginning, to figure this thing out. On the other hand, I can admire a staunch refusal to provide an introductory crawl or even an onscreen title card announcing a location at any given point. He’s asking if not forcing us to figure a few things out for ourselves, so I give him credit for that and maybe it’s just my own problem. I once read a quote where somebody referred to Fincher’s ZODIAC as ‘being locked in a filing cabinet for three hours’ and that was a film with suspense sequences and a fair amount of humor mixed in there. With an overwhelming avalanche of info in every scene that made me almost want to give up out of sheer intimidation, PRINCE OF THE CITY really is like being locked in a filing cabinet for three hours but the immense volume of what’s going on does begin to have an effect by a certain point and at its best the film does achieve a certain power through its density. Like many of his New York-set films, Lumet’s dry style can seem a little too much like the New York Times business section when it could use just a touch of the front page of the Post but ultimately it’s a film that offers considerable rewards for sticking with the increasing stakes that continually build over its lengthy running time.

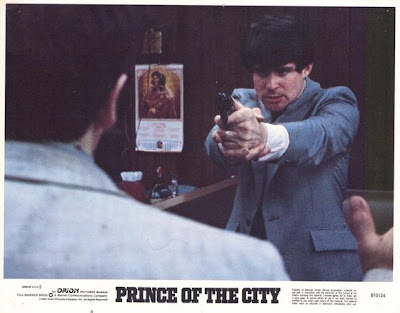

Based on the true-life case of New York cop Robert Leuci, PRINCE OF THE CITY tells the story of New York Police Detective Daniel Ciello (Treat Williams) of the Special Investigative Unit, a team of narcotics investigators who answer to practically no one with the power they have, veritable “princes of the city” as far as everyone is concerned. After Danny is involved in what he feels are some questionable actions he begins discussions with an internal affairs group known as the Chase Commission and, saying that he has been directly involved with three separate incidents involving corruption over the years, agrees to assist them to expose what’s happening on the sole condition that he won’t have to rat out any of his partners, which they agree to. But as time goes on, some investigating officers drop out and others getting involved, with other interests coming into the mix Daniel begins to learn that having that promise kept may be next to impossible as he finds both himself and his family deep in a situation that will go on longer than he ever imagined and one he may never be able to find his way out of.

Definitely not a work of simple narrative, you could imagine notepads being handed out to people as they enter the theater to help keep track of it all. With sections of the story introduced by merely displaying I.D. cards of various officers involved with the case on both sides the screenplay by Jay Presson Allen and Lumet based on the book by Robert Daley never gives us a scene that spells out everything for us like we’re two year-olds, let alone a moment where Williams gets a simple anguished “That’s why I gotta do this” monologue and reveals exactly why. As if to prevent the protagonist from ever being fully let off the hook, such a speech never happens. The longer I stayed with it, the more I found PRINCE OF THE CITY to gain in power, particularly into the second half as I began to get a true sense of Ciello’s feelings of drowning in his life, of feeling lost at how guys he was depending on through his continuing ordeal get shuffled off to another department, at how the magnitude of what he promised to do becomes more clear, more terrifying. Since Treat Williams is onscreen about 95% of the time it shows almost everything from the point of view of Ciello, a cop who certainly isn’t pure but thinks he can get all this to work on his own terms maybe while dealing with some sort of guilt that he can’t even figure out how to admit to himself, let alone to anyone else. But it’s impossible for him to fully know the size of the machinery he gradually finds himself up against, his initial hopes to get all this over with quickly collapsing beneath him just like what happens to the chair he sits in during his very first visit to internal affairs. It’s based on a true story so it’s pretty clear going in that this isn’t going to be a simplistic action movie where his partners come after him for revenge. Where the conflict comes from instead is the full weight of the narrative, how Danny doesn’t know what the cost is going to be to him and his family, how he’ll never know who he can trust--certain individuals he deals with may be on the side of the law (like Bob Balaban’s immaculately tailored, utterly loathsome Washington official) but that doesn’t mean they’re on his side and the ones who would presumably be the stereotypical mobsters or corrupt cops are the ones who seem more willing to say what’s really going on to his face. After running into somebody who might turn out to be trouble, Danny says, “He’s not a doer he’s a talker. Which is probably worse” and in this film’s world that’s what is true. What Leonardo Di Caprio’s undercover cop in THE DEPARTED goes through looks like a cakewalk when compared with what Danny Ciello has to go through over the course of what turns out to be years.

At an early stage in its development PRINCE OF THE CITY was to be directed by Brian De Palma (it seems that De Niro and Travolta were both in the mix as possible leads) with one sequence from his version ultimately becoming a key flashback in BLOW OUT. It’s easy to imagine how that would have been a completely different film and Lumet of course goes more for a certain bookish naturalism through his straight-ahead style, as if exploring just how much pure information he can insert into a narrative before the viewer’s head explodes. The style is definitely locked into the 70s, moving quickly through sections past the sheer magnitude of what is being discussed or shown before one has a chance to process any number of things and even the courtroom scenes—a relatively small amount of the running time—come off as overwhelming in how they ellipse a huge amount of info into a montage that effectively shows how this process really works, certainly not how testimony is given in only five minutes like every other film. It takes a considerable amount of time for a viewer to adjust to this onslaught and one can only follow so many of the details of names, events, Ciello’s relationships with his partners, his decision making, interacting with his family, what has to happen to them, where he meets the prosecutors, what they say to him, how they respond to what he says to them and so on, with characters drifting in and out of the story in a way that adds to the believability. As a result it took me over an hour into this 167 minute film (and, yes, you feel that length, almost to give us an inkling of how overwhelming all this is for Ciello) before I felt like I could really get a hold of things. It’s not an ideal way to process a movie but it feels essential to what Lumet is going for. It also remains, by his own admission, deliberately ambivalent towards what its lead character has done to the very last shot and whether or not he’s at all someone to be admired. The film almost wants to pummel us with everything until we can totally understand what Ciello is going through whether we’re ever going to be on his side, leading to the question of what really is justice where the law is concerned and what really is corruption where the police are concerned. Hey, I’m only human and I guess I kind of wish that the film were easier to get a handle on to follow along with things but it does get its point across and the way Lumet gets it all to come together, to get those final few minutes to pay off as well as they do, is admirable. Of course, the director kept working at a steady clip through the coming decade with his final film (to date) released only a few years ago—his subsequent film DEATHTRAP followed only seven months later—but it’s hard to imagine he would have been allowed to make PRINCE OF THE CITY, at least with the same running time if not the same intensity of purpose, even just a few years later.

Not as instantly connectable as a few of his other films, like the escalating suspense of the much more compact DOG DAY AFTERNOON, it also doesn’t have the same sort of powerhouse lead. Pacino would have probably been too familiar a choice because of SERPICO, Travolta might not have been quite right and Alec Baldwin, who would have been brilliant playing this material, was still more than a half-decade away from making his first film (now in my mind I’m dwelling on how unfortunate it is that Lumet and Baldwin never worked together). Williams rightly plays this as the performance of a lifetime, sweating through every bit of anguish to an inch of his life but at times I can’t help but think that his lengthy speeches about his plight just have a few too many words in them that he has to fight through a little too hard but of course this movie has too many of a lot of things. He’s not as strong as certain other actors may have been in the part but his charisma as one of these princes is very evident, his desperation is palpable and his earnest belief that he can make it all work for himself carries what he’s doing throughout. Playing opposite him in the very large cast supporting cast with certain people doing excellent work are Lindsay Crouse as Danny’s wife, Jerry Orbach (playing one of Danny's partners, a rough draft for Lennie Briscoe if there ever was), Bob Balaban, Norman Parker, Carmine Caridi, James Tolkan (getting a chance to play some particularly strong moments in the second half), Lance Henriksen, Lane Smith and Lee Richardson playing an unctuous, well-tailored attorney whose demeanor anticipates James Mason in Lumet’s THE VERDICT. Most surprisingly, a very young Cynthia Nixon from SEX AND THE CITY appears briefly as a teenage junkie.

If anything, a film about a protagonist tortured down to his core, alienated from his friends and left staring at a veritable void wondering what his life has become is at least something I can identify with at this point in time. A film that demands you stay with it to appreciate the power of where it leads to, as well as every bit of fear and guilt its hero is going through, PRINCE OF THE CITY has never been one of the most popular Lumet titles and only received one Oscar nomination, for Best Adapted Screenplay. In his excellent book “Making Movies” Lumet doesn’t give the production any special emphasis (most impressive: it was shot in 135 locations over just 52 days) but it might be the most purely Lumet film, for both good and bad. It’s not his best work—what, you want me to choose between 12 ANGRY MEN, FAIL-SAFE, SERPICO, DOG DAY AFTERNOON, NETWORK and others? That’s a tall order. Like I’ve indicated, PRINCE OF THE CITY isn’t an easy viewing experience and even if Danny Ciello will be forever conflicted within himself about where he winds up seeing his journey to get to that point is ultimately a worthy one. No one ever said that films had to be easy anyway.