Friday, September 12, 2014

The Ephemeral Is Eternal

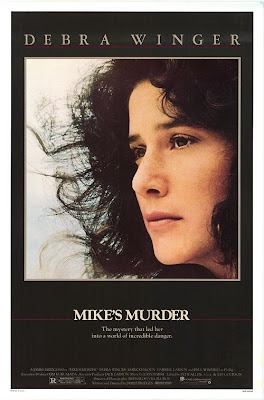

“This is an age of movies for children, but it will pass.” Paul Mazursky said that in a 1984 People Magazine profile of John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands. Putting aside how the idea of that magazine doing an article on those two now seems like it comes from an alternate dimension, Mazursky’s statement sounds like something looking hopefully towards a future that never actually came to pass. After a long, loud summer at the movies it only seems more so. Also out of place back in 1984, not to mention right now, was James Bridges’ MIKE’S MURDER starring Debra Winger which barely even got released at the time. Opening in 80 theaters in March of that year on the same day as Tom Hanks’ starring debut SPLASH, MIKE’S MURDER quickly disappeared in spite of it being Bridges’ followup to the hit URBAN COWBOY where he and Winger had first worked together. By this point Winger was even hotter after AN OFFICER AND A GENTLEMAN and TERMS OF ENDEARMENT but if MIKE’S MURDER is remembered at all now it’s often more for what happened to it than the actual film—after a test screening that the director himself once called “disastrous” the film underwent massive reediting essentially reworking the sequence of the film, straightening out what was originally intended to be a non-linear structure. Scenes were cut, others were reshot and John Barry was brought in to replace the original music score by Joe Jackson. None of the extensive changes did much good in terms of the response when the film eventually was released over a year later--Vincent Canby in the New York Times was mostly dismissive and even now Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide calls it “one of the worst films by a filmmaker of Bridges’ stature” adding that the only reason the film didn’t receive a BOMB rating is because “several critics thought highly of it”. Over two years after it opened a New York Times TV listing of an airing advised readers to ‘skip it’ leading Pauline Kael to write on the film for the first time, imploring anyone to “please don’t skip it” and essentially giving it a rave, calling it Bridges’ “most original and daring effort”. The film never really expanded to a wide release and maybe Warner Brothers was more than happy to let it just fade away into one of those clamshell cases their VHS tapes used to come in but often that’s what happens to movies out of time. This was certainly one of them, a 70s neo-noir character study turning up well into the following decade when people wanted, well, SPLASH. Now, 30 years later, the film still has some (if not many) people who think “highly of it”, occasionally turning up in message boards to ask if the Warner Archive which has made the release version available might put out the original cut one day. Even if what we have now isn’t what it was originally meant to be MIKE’S MURDER remains an original; sad and piercing, an L.A.-set mood piece that could be paired with something like NIGHT MOVES but also at its heart a true character piece that’s not about solving a mystery but about the lack of connection you ever really have with people you meet in this town. It’s a flawed film, a sad film as well as a fascinating one as well that in addition to featuring one of the very best Debra Winger performances gets at yearning and loneliness in Los Angeles in a way that few films have ever attempted, let alone express any interest in. It nails how empty the town can seem late at night when you know the phone isn’t going to ring. Whatever its problems and whatever went on in the cutting room it’s a film with a soul deep down than you can’t quite shake. Brentwood bank teller Betty Parrish (Debra Winger) has had a longtime on-again, off-again (but mostly off-again) fling with Mike Chuhutsky (Mark Keyloun), a tennis instructor and small-time drug dealer who drifts in and out of her life. Shortly after he drifts into it once again, Betty receives a phone call telling her that Mike has been murdered, something going wrong on one of his drug deals. As Betty tries to piece together who Mike was and what he may have been into she learns surprising details about his life without realizing that what he was doing may have placed her in jeopardy as well. Even though it runs under a minute and a half, the MIKE’S MURDER theatrical trailer contains a number of shots not seen in the finished film, almost as if it’s advertising a different version entirely—even seen out of context a few shots seems more stylized than anything in the final film, making me wonder if this is a clue towards how the original version may have played and it could be argued that the trailer fills in some exposition that the movie itself never quite gets around to. Even if MIKE’S MURDER (also written by Bridges) can’t be called of the great Los Angeles movies—in this form it’s possibly too disjointed to achieve that label—it allows for a look at the city that few other films provide finding the balance between those houses up in the hills that we wish we lived in and those places we probably shouldn’t be finding ourselves late at night where certain drug deals or who knows what are going on. The film’s portrayal of gays, particularly Paul Winfield's record producer, feels both sympathetic and matter-of-fact as well as if being presented by somebody from the inside who fully understands it. All through the film Bridges pays attention to these people, to their glances, their silences, their surroundings—the few moments of watching the massive chili burgers being made at a Tomy’s (not Tommy’s, the name of the ones I’ve been to—looking up the name, this may be Culver City) early on almost feels like a short film in itself, a reminder that I used to eat those burgers years ago but don’t think I could do it now without fear of a heart attack. Even a brief scene in a sushi place is a reminder of how early 80s LA just the idea of eating sushi was. The Brentwood setting is certainly an echo of when I worked in that part of town (yes, I’ve written about that recently but sometimes in my head I just get drawn back there). MIKE’S MURDER is around a decade before I turned up but it still seems like much longer. Mike’s apartment is at 1020 Granville Ave. (just a short drive over from Bundy, incidentally), Betty mentions jogging up Barrington and it makes me wonder what was really going on with certain people I encountered, people I never knew as well as maybe I wanted to. Even the connections I don’t have intrigue me as a result like the extensive location shooting down in Venice, a place I’ve never spent that much time in and haven’t even known someone who lived there since the mid-90s. A drive down Sunset occurs around the same places where the car chase in AGAINST ALL ODDS, released just one week earlier back in ’84, took place and that’s a slick, enjoyable film (one I should write about, but another time) but the L.A. of MIKE’S MURDER feels like a city that I recognize even now, one that is lonely, sometimes a little too overcast in the middle of the hot days and some nights that go on longer than you’d like. Along with that examination of the city it’s a character study, probing into the close-ups of Debra Winger’s Betty Parrish as she tries to find out about Mike, not just his murder. She doesn’t really know anything about him. She doesn’t even know why he talked about her to people. He doesn’t seem good enough for her, like he’s trying too hard in his little jokes, but he does represent something that she can’t explain, maybe because it helps her feel like something more than a humdrum bank teller waiting to hear about a promotion that probably isn’t any big deal. As it is, she’s barely present when talking to friends and most of her connection to the world seems to be from her answering machine, even as people try to look at her through their own prism whether windows, video cameras or the photos Mike’s friend Sam incessantly snaps of her without even asking first. Betty, who can’t even feign interest in what her artist friend is pretentiously yammering about over sushi for more than a few seconds, and her teacher friend Patty who doesn’t do anything crazier than order extra onions have no place in this scene. Nobody wants to discover that they’re one of the Rosencrantz/Guildensterns of the world but that’s what the characters of MIKE’S MURDER seem to be quietly--or in some cases not so quietly--dealing with and that’s what L.A. sometimes turns you into. And part of that feeling is learning how little you even knew about how you fit in to certain lives like what Betty finds out about Mike. It almost makes sense how it never feels entirely explained just how much she really knew him. “You still living in the same place?” Mike asks Betty after not seeing her for months. “Same place,” is her reply and it feels like an exchange from my life. Maybe it’s the structural reorganization that makes things feel a little unclear as if whatever happened between Betty and Mike outside of the tennis court feels like somewhere between a one-night stand and something else—-dialogue seems to reference a trip out to Catalina although that’s all we ever hear of it--but how much is never entirely clear and some shots only seen in the trailer certainly indicate more. Some of the seams from whatever happened in the editing room show at times, like a scene that introduces Paul Winfield which not only seems to play much of its dialogue offscreen as if looping in new stuff after the fact it probably could have been easily lost anyway. The film’s second hour after Betty learns of the murder apparently all takes place during one day and for reasons I can’t quite pin down I wonder if this would have flown better in a flashback structure —that the titular murder was also graphically seen in some form (including being glimpsed in that trailer) is certainly an indication that it once played like a considerably different movie. Since the main character is where much of the interest lies when the focus moves away from her to scenes involving Mike’s friend Pete played by Darrell Larson the interest doesn’t hold, as if the movie is trying to convince us that there’s more plot than there really is. Music by Joe Jackson was dropped—although the album billed as the film’s “soundtrack” came out anyway and listening to just one track makes me imagine how different the film would have been with it—in favor of a new score composed by John Barry but while it’s well done is almost too familiar, too BODY HEAT while still getting at something within these people and the feelings they just can’t shake. It’s the moments that linger, the loneliness in the air, even the detour into the party made up of early 80s performance art, another place where Betty is observed through the prism of video cameras—it’s one of those early 80s films where you can tell the decade hasn’t fully decided what it wants to be yet, just like Betty hasn’t decided who she is—that you remember. This is the 80s in L.A., the film seems to be saying—drugs (“the only thing that matters,” Mike’s friend Pete cries) and videotape. In this context, the stripped-down climax as Betty’s home is invaded by one last strand of her connection to Mike is queasily effective, selling us the isolation of Betty’s tiny house and keeping to her point of view, as Darrell Larson’s Pete screams “You’re like all the rest!” when she’s about to betray him. “No,” she as if to simultaneously mollify him and deny the real truth to herself, that her relationship with Mike could never really turn her life into anything more special than it is. There’s a bluntness to the way Bridges plays the suspense, he knows exactly how to stage the moment and not suddenly turn the film into something else. “Where’re you going, Mike?” she asks early on as she drives him, her voice indicating she wants to know more than whatever his destination might be. And she never really gets the answer. It’s not about solving Mike’s Murder. Betty’s even told she doesn’t want to know anyway. It’s about the realization that there can be no solving the mystery of Mike. We don’t get those answers. We rarely do. Some brief connections are just never what we want them to be. Chaz Jenkel’s “Without You” played over the end credits sounds a little incongruous after the ending but it serves as a reminder of when it was heard on the radio earlier as Betty drives Mike up to the house on Doheny. It’s those songs that stay in your brain because of those moments that remain with you because of that other person for reasons you never fully understand. Maybe since things are missing those moments are what MIKE’S MURDER can be in the end which if anything is a lot more than some films have. Without having to be an appendage to the likes of Travolta or Gere it allows for MIKE’S MURDER to give us a Debra Winger performance that is totally untethered, allowing us to simply observe what makes Betty unique enough that someone like Mike is drawn to her but also what makes her completely ordinary as well and it’s that strength, that defiance, which holds the film together, regardless of what happened in the cutting room. Paul Winfield (reportedly essentially playing himself—the film is partly based on what happened to someone he knew) is searing in his own intensity as well, much of his performance in just one extended scene. “Help yourself, everyone else does,” he says to Betty, a person resigned to being host of the neverending party, shrewd enough to understand his connection with Betty and how they’re both in love with the same person while very much aware that it’s never something they can fully explain to each other. Much of the rest of the cast is made up of unknowns although Brooke Alderson as Betty’s friend was also in URBAN COWBOY and William Ostrander as one of Mike’s friends was Buddy Repperton in CHRISTINE. Mark Keyloun, a Barry Miller-type whose other credits include SUDDEN IMPACT from around this time, plays Mike as the enigma he has to be but is maybe too callous, too immature. We don’t quite see what everyone else does but we know they believe it. In comparison, Robert Crosson as Mike’s quiet photographer friend Sam who has his own feelings for Mike is where we get the true amount of regret and loneliness from. That’s where the sadness lies. Maybe it makes sense that Mike would never pick up on what all these people around him are feeling but it still feels like a void at the center. It’s an ongoing question—what is better, the quality film that doesn’t have much staying power or the flawed film that even months later we can’t quite shake, wondering about the holes in there. What are movies in the end, really? What do we take from them? When the film came out Bridges was quoted as saying, “I think this is a better picture than it was and I never would have allowed it to be released otherwise” but let’s not forget that he was in the process of publicizing the picture at that time. Betty plays the straightforward chords on her piano—a remnant of the non-straightforward original structure—the one with the C scale out of tune that Mike spoke of, her life out of tune. It’s a movie about being an adult. In some ways, a film about lost innocence, how that innocence is impossible. Whether we’re seeing what the movie was meant to be might be open to question—interestingly, also from Warner around this period was Jonathan Demme’s SWING SHIFT, another film with a female lead which went through a similarly protracted postproduction process leading to people through the year’s wondering what might have been. The final moment of the only MIKE’S MURDER we’ve ever seen feels a little like a reshoot, whether it was or not, to give us some semblance of hope in a story that really can’t have any. In some ways that final moment feels like an acceptance of loneliness. Sometimes you have to do that in L.A. Like the song over the end credits, certain people stay with you in moments like that whether you want them to or not. There’s not as much hope found there as there usually is in an age of movies made for children but how important that is in the end is maybe up to you.

Thursday, July 31, 2014

How Infinite In Faculty

The night before my birthday in June this year I revisited Jonathan Demme’s STOP MAKING SENSE at the New Beverly. It seemed to make sense for the occasion and this was one of those cases where even though that Talking Heads album had long since been seared into my brain I hadn’t seen the actual film in years. Even though the performance of “Once in a Lifetime” was in heavy rotation on MTV back in the day I think revisiting the number again in context after all this time was almost emotionally overwhelming for me. It is kind of a perfect birthday song, after all, much like how I once decided that Boorman’s POINT BLANK was a perfect birthday film. After all, how did I get here? How old am I now, again? The next morning I drove up to Griffith Park Observatory and looked out at the city, silently thinking about these things, the lyrics continuing to echo through my brain. I dug out an old cassette of the soundtrack and kept listening to the song, wondering about myself just as I imagine anyone in the world wonders about themselves while it plays. It’s still with me now. Maybe more than usual, maybe just as much, as I try to figure out where I’m going. And maybe more than ever it all seems murky, every day another reminder that I don’t know what the hell I’m doing. Some may have forgotten but “Once in a Lifetime”—and, specifically, the STOP MAKING SENSE performance of it—is heard over the opening and closing credits of Paul Mazursky’s DOWN AND OUT IN BEVERLY HILLS, one of the biggest successes to ever come from the director who passed away at the age of 84 on June 30.

I’d heard rumors for some time that Mazursky wasn’t doing well but he fortunately had been able to witness a small sliver of tribute in the months before at a tribute when Cinefamily programmed a few of his films over several nights including an evening where he took part in an onstage discussion with screenwriter Larry Karaszewski, followed by a showing of his 1971 film ALEX IN WONDERLAND. They covered the bases of his career from The Monkees to Fellini to Kubrick to the films he directed and while he was obviously somewhat weak he seemed genuinely pleased to be there and it was a thrill to hear his stories. Several weeks later, Illeana Douglas presented a rare 35mm screening of his 1978 smash AN UNMARRIED WOMAN at the theater, finally giving me the chance to see that film—the DVD is out of print and something should really be done about its availability particularly now. That film isn’t as known these days as well as it deserves to be but maybe that’s one of the conundrums of Mazursky’s career, a director who made films that were smash hits in their time but are maybe so locked into the era in which they were made so haven’t stuck around in the consciousness of filmgoers beyond those who take the time to remember. And now, there really aren’t any directors like Paul Mazursky left at all. Same as it ever was.

Released at the end of January 1986, DOWN AND OUT IN BEVERLY HILLS wasn’t the first picture released by the Disney Studios offshoot Touchstone—SPLASH had come out nearly two years earlier—but it was the first under the Eisner-Katzenberg regime. It certainly feels like the first real Touchstone film in how it featured recognizable stars in big splashy vehicles as a cheery voiceover guy excitedly blurted out “Touchstone Pictures Presents!” in the trailer. It also has considerably more depth to it than the formula eventually allowed but DOWN AND OUT IN BEVERLY HILLS was also an R-rated adult comedy where the gross actually went up in its second week of release (as an aside, I saw it opening weekend—the first Saturday afternoon showing at the Yonkers Central Plaza was sold out. When I returned for the next show it had been moved into one of the big theaters, I think kicking the Rob Lowe hockey movie YOUNGBLOOD into the smaller screen) and went on to be the 11th highest grossing film of the year. It was a different time, of course. DOWN AND OUT is very much a Paul Mazursky film of that different time, comical and poignant, deeply personal, extremely funny at times, unavoidably dated and yet there are scenes that wouldn’t really need to be changed at all if someone were to remake it in 2014. Broader than Mazursky’s 70s output and not as essential now as some of them feel, I’m not sure it’s quite as uproarious as it was in ’86. I’m not sure that matters anymore.

Wealthy Beverly Hills clothing hanger manufacturer Dave Whiteman (Richard Dreyfuss) is feeling unsatisfied with his life, unhappy in his marriage to Barbara (Bette Midler), having an affair with his maid Carmen (Elizabeth Pena), daughter Jenny who refuses to eat and teenage son Max (Evan Richards) going through his own sexual confusion. When one day homeless Jerry Baskin (Nick Nolte), having lost his beloved dog, enters the Whiteman’s backyard to drown himself in their pool. After saving his life, Dave tries to help out Jerry but Jerry soon is changing the lives of the family members in ways that they never would have imagined.

Based on Jean Renoir’s BOUDU SAVED FROM DROWNING and the play by René Fauchois with a screenplay by Masursky & Leon Capetanos, DOWN AND OUT IN BEVELRY HILLS has a tighter pace than many of the director’s films, getting right to the point and not overstaying its welcome at 103 minutes. Looking at them now it feels like the Paul Mazursky cinematic view of the world made the most sense in the context of the 70s, in the BLUME IN LOVE and AN UNMARRIED WOMAN period, a decade which he portrays the journey of in his Truffaut homage WILLIE AND PHIL. Coming six years after the release of that film, the more blatantly comical DOWN AND OUT IN BEVERLY HILLS is just as much about its own moment, coming within the ever-growing rot of the Reagan era and the harsh sunlight caking down onto the cement. Maybe it’s because of the weather in L.A. lately but I look at the shots of the Whiteman’s house and surrounding neighborhood and it always seems so hot and garish, no shade to bring a moment of peace to anything. Even though the film is set during the holiday season it never feels that way in the slightest (the inherent Jewishness of the Whiteman family feels intentionally buried as well). Dave Whiteman feels guilt that no one else around him feels, the guilt that no one in the 80s felt—ultimately, the film is about coming to terms with that guilt and doing something with it. He’s another Mazursky protagonist who, as successful as he is, doesn’t understand how he actually got to this place, as certain song lyrics declare, and isn’t sure what to do about it now that he is.

The director clearly looks at Beverly Hills as a place everyone wants to be and when they get there everyone suddenly becomes the same, all with the same gleaming white Rolls Royce, with each person forced to find themselves once again just as Barbara seems to surround herself with mirrors in her bedroom as if to somehow try to remind herself that she’s still a person. In his own films Blake Edwards always gives the impression that he would be perfectly happy to burn that world he lives in and loves down to the ground, letting the homes crash into the canyons below. With Mazursky the self-loathing feels more internal as if he’s trying to knock down the walls that are within himself and come out the other side somehow changed. Achieving his wealth via clothes hangers feels so deliberately absurd that you wonder if to him it makes about as much sense as being a film director.

Even the memories of the director’s past films linger in the air—Dave observes, “It’s like the 60s,” when Jerry takes him down to Venice Beach, that place where HARRY AND TONTO had its final moments, it’s an odd reminder of the past for the director, a place that he hasn’t thought about in a long time. There is screwball at the heart of DOWN AND OUT but for a movie that’s essentially a comedy, an attempt at a light Shakespearean romp, it feels almost surprisingly introspective and curious about its people. From the nitpicky dialogue where characters obsess over enough white meat in their Thanksgiving turkey, Dreyfuss’ aggravation or the growing insanity of the climactic New Years’ Eve party, he laughs don’t interest Mazursky as much as the open therapeutic nature of it, as if the film itself is as thrown by Nolte’s bluntness as the characters are. It’s a film that acknowledges that sometimes people don’t know what the hell to say to each other. The Touchstone formula hadn’t quite been cemented yet so there’s still some ambivalence about it all, particularly concerning him, it’s willing to let itself breathe at times.

What strikes me now is a certain distance I feel from some of it—maybe the 80s broadness gives me bad flashbacks, maybe the fashions do, maybe the more character oriented BLUME IN LOVE sticks with me in the end since it’s that much more about probing into the angst of its lead characters. DOWN AND OUT doesn’t want to go that deep (it does dig deeper than your average studio comedy digs now, to be fair) but it does let the characters deal with each other, making that uncertainty about itself. Plus there’s Mike the Dog playing the family pet Matisse, a joke that shouldn’t work as well as it does, one of the best dogs ever in a movie and could very well be as much of a reason for how big a hit the film was as anything (well, that and the sight of Nick Nolte eating dog food). Maybe I shouldn’t like how much Mazursky uses him as such an obvious button but it works and for that matter few directors were ever so lucky with a dog to cut away to. Matisse even has a dog psychiatrist (played by Donald F. Muhich who played essentially the same role for the director several other times), which plays now as an example of how the film as dated since the joke doesn’t seem as zany as it does then.

It’s one of the problems of the movie now--the sexual confusion of the son isn’t as riotous as it might have seemed then and even if Jerry’s immediate acceptance of him plays as somewhat sweet it does plant the film into the time. But there’s still cockeyed affection for all the people in it and as silly as he might portray some of them you can tell that deep down he likes all of them. Mazursky doesn’t claim to have all the answers (his films are often about people who come to the realization that they don’t have all the answers) which seems brave now when most films seem to want to have a character espouse whatever the theme is. He knew that no one has the answers. We still don’t—revisiting this film in 2014 is an uncomfortable reminder that there seem to be more homeless in my own neighborhood these days than in past years. In the film’s final moments there’s a look on Nolte’s face that displays a certain ambivalence about the decision he’s making, even if he knows that it’s the right one, a moment that I don’t think would have been found in certain Touchstone films later on and almost by itself causes the film to stick more than it might have. It may be one of Paul Mazursky’s minor films but, as broad and commercial as it is, it’s as essential as any of them.

This was actually the first film in several years for both Bette Midler and Richard Dreyfuss so it served as something of a comeback for each of them and they mesh with the style perfectly, both with expert timing and a willingness to dig into these characters, making their interplay achieve a music within the familiarity the characters feel with each other. They’re clearly rendered speechless in some ways by Nick Nolte’s character and that lends an unpredictability to it all since everything he does is totally unexpected, not even aware that he’s in a comedy. He doesn’t reveal anything to us except for that one look at the end so even then Jerry feels like a mystery to us, let alone everyone else and Nolte wisely keeps that enigma going. Little Richard drifts in and out of the film commenting on the action as next door neighbor Orvis Goodnight while Mazursky, who turned up in all his films as well as many others, plays the Whiteman’s accountant.

It had been a long time since I’d seen this film but was able to find a DVD at the Barnes & Noble in the Grove, right near the area of the Farmers’ Market where he famously presided over many breakfasts with friends for years. That seemed fitting--someone I know said that there should be a plaque commemorating him around there and there should, preferably somewhere over near Bob’s Coffee & Doughnuts. DOWN AND OUT IN BEVERLY HILLS was one of Mazursky’s biggest hits and perhaps his last although ENEMIES, A LOVE STORY garnered a good deal of acclaim when it was released several years later. For the record, I also worked a lowly crew position on SCENES FROM A MALL when it shot in Connecticut but I’ve tried to put that out of mind (I don’t blame him). And now, all these years later, I’m still wondering how I got here. Through his long career Paul Mazursky’s films didn’t always connect, with either myself or the rest of the world, but his intensive exploration of personal was at times brave and it was nice knowing that he was there, somewhere in the city of Los Angeles, presumably having breakfast at the Farmer’s Market. In May I tweeted a photo of the wreckage of Hollywood Boulevard as portrayed in the recreation of Saigon in ALEX IN WONDERLAND. Mazursky himself retweeted the photo, adding simply “i was there”. And he was. Maybe, in the end, it doesn’t matter how you got there and whether you belong, something that Dave Whiteman in DOWN AND OUT IN BEVERLY HILLS seems to spend too much time obsessing over. Maybe all that really matters is that you were there, somewhere that mattered to you, and that you spent the time you had doing something. Because, no matter what, there will only ever be a limited amount of time to do it. Same as it ever was.

Monday, June 30, 2014

How We Lower Our Sights

June 17, 1994: the now-legendary O.J. Simpson slow speed Bronco chase. The world was riveted. Everyone was watching. And yet you just know that there were a few people out there who missed it because they were in a movie theater seeing Mike Nichols’ WOLF which opened that day. The summer of ‘94 is a time that I have particularly vivid recollections of since I was actually working at a bookstore job in Brentwood. It was in the same shopping plaza where Nicole Brown stopped off for Häagen-Dazs on the way home, right across the street from Mezzaluna and just a few blocks away from 876 S. Bundy Drive. Kind of like being in Dallas when the assassination happened, if you get my meaning. I’ve got a few stories that I used at cocktail parties through the years about encounters I had with certain people connected to what had happened (ask me some other time) but none of them have to do with the Bronco chase since I wasn’t around--I had the day off, part of which was spent across town in the first showing of WOLF at the Cinerama Dome earlier that afternoon, of course. But the fact remains that this is one of those things where the release of the movie has been inexorably tied into what was happening that day and for all we know caused the film to slip through the cracks for some people. Ultimately making a not-bad, not great $65 million at the box office, WOLF is a good film, one with goals and thoughts behind it but for a variety of reasons feels like something that was aiming at multiple targets and didn’t quite hit each of them. Compelling all the way through but maybe not completely fulfilling, twenty years later it still engages with a wit to its look at the world that helps greatly. It’s clearly from another time—very much a pre-O.J. film released just as O.J. happened, if you will, and even if Mike Nichols’ ultimate goal in exploring the material doesn’t feel one hundred percent clarified it plays now as refreshingly adult even if the intellectualization behind the approach doesn’t hold all the way to the end.

Shortly after being bitten by a wolf up in Vermont while driving home New York book editor Will Randall (Jack Nicholson) is informed of the termination of his position after billionaire tycoon Raymond Alden (Christopher Plummer) has bought up the company. He’s even faced with the humiliation that protégé Stuart Swinton (James Spader) is to replace him and although immediately resigned to this fate Will’s personality soon begins to undergo extreme changes which leads to learning a secret involving wife Charlotte (Kate Nelligan) and his decision to finally take action over his place at the company. Things change for Will even more when he meets Alden’s wild card daughter Laura (Michelle Pfeiffer), finding in her another person he can actually talk to and connect with, just as the animal side of him brought out by the wolf bite is beginning to make itself known.

Not even 15 minutes into WOLF Jack Nicholson’s Will Randall lays out an intriguing thesis: “You could make the case that the world has already ended. That art is dead….that instead of art we have pop culture, daytime TV, gay senior citizens, women who have been raped by their dentists confiding in Oprah, an exploration in depth of why women cut off their husbands’ penis…” Spoken by a character who believes with reason that his world is about to collapse in on itself, it partly works as what WOLF is about but even more than that is a reminder of how the film opened on one of the key pop culture events of the last decade of the twentieth century, an event that led to most of us hearing the name “Kardashian” for the first time, where everything would become one giant hellish reality show. The end of the world, you could say. Bit player Allison Janney (THE WEST WING still five years in the future), presumably playing some sort of la-di-da New York media type, tries to naively argue that money doesn’t imply ruthless ambition which is something that even the hardened billionaire she’s talking to doesn’t try to deny. WOLF is aware that polite, pipe-smoking way of doing business is fast on its way out, equating what is to come with a certain animalistic way of humanity, where talent doesn’t matter anymore, where the notion of civility flat out doesn’t matter. The “old fashioned way” of begging isn’t how it’s done anymore and what happens to Will isn’t just inevitable but in some ways actually for the best if this is what the world is to become, turning him into a wolf but also a man, with a capital “M”, for the very first time and not just a polite suit.

On a conceptual level WOLF plays as a horror film made by someone with no particular affinity for the genre or even awareness of how to pull off things like jump scares but is presumably attracted to the concept anyway, possibly with other goals in mind. Kubrick’s THE SHINING, coincidentally also starring Jack Nicholson, certainly contains elements that allow it to fall into this category and based on WOLF I don’t think that Mike Nichols has disdain for horror so much as him never having given the subject much thought at all. It really feels like Mike Nichols making a Mike Nichols film set in a Mike Nichols world where people drink fresh ground coffee from Zabar’s invaded by something else, a straight horror film crossed with the metaphor of embracing one’s inner beast in this day and age. There’s a constant feeling that the director is trying to bring something to the material above and beyond just shooting the script he was given (more than you could maybe say about several other latter day Mike Nichols films) it’s just that he’s not sure exactly what that should be. Since it doesn’t seem to know the basic pattern of a horror film it doesn’t know what clichés it should or shouldn’t ignore which allows for its own unique approach how characters interact in ways. The themes are there, very much so, but it also feels like through multiple rewrites and reedits and working out the effects and all that by a certain point exploring the metaphorical implications had to be dropped in favor of just making the film and getting it finished. Which had to be done, of course, and it’s not particularly surprising that the result isn’t a straight ahead horror film that goes heavy on the gore.

What Mike Nichols is interested in is going to be more interesting than what he’s not, what he can immediately connect with is going to be that much more tangible cinematically. But it does leave WOLF slightly wanting in the end, an array of engaging elements dropped during the second half as the film closes in on a conflict with just a handful of characters along with a climax, apparently greatly reworked during production, that is maybe a little too rote in how some of it plays out. Nichols seems to embrace the imagery and how the mood brought on by Ennio Morricone’s score affects the multiple helicopter shots gliding through New York at night (something else that gets me to think of THE SHINING) plus to his credit makes the ‘Jack Nicholson is a werewolf!’ element of it all much more low key and ambivalent than you would expect. But it’s almost a shade too polite making the occasional overly hyper zoom to underline something feel not quite right as Nichols searches for something to do with his camera. The wit and energy of the publishing house setting is what has the most zip to it all and, maybe like Nichols, I’m more intrigued by how the great director of photography Giuseppe Rotunno shoots the famous Bradbury Building (a familiar L.A. location even though the film is set in New York) than the delirium of the wolf’s runs through the woods at night.

As the film goes on the camera seems to push into close-ups more and more, omitting the world around the few characters, and since Nichols is definitely a director who knows what to do with close-ups, that’s where he finds the most to be interested by. When he’s not in his element the ideas just aren’t there in the same way so when the climactic action kicks in it feels like he’s finally agreed to make the film the studio probably wanted all along. The werewolf makeup effects feature the expected strong work by Rick Baker (along with some intriguingly subtle changes to Nicholson over the course of the film) but I don’t think Nichols has much interest in that either. It’s the intimate moments that have the most impact, such as Nicholson’s confrontation with Spader at a urinal that includes a particularly good offhand mention of “asparagus” to cap the scene. In comparison, the climactic showdown is a little more what’s expected and while it actually doesn’t go on forever like such a sequence might today in my memory it sort of seems like it does. It’s not a bad climax, as these things go, it’s professionally done. It’s the climax to a movie. It just may not have been the right climax for this movie as much as it was the right climax for a major star vehicle released in the summer of ’94.

Much of it remains intriguing, more on a human level than anything and thanks to the lunchtime conversation between Nicholson and Pfeiffer few other films ever made have made me want a peanut butter and jelly sandwich so badly. As the connection builds between Will Randall, a good man fighting against the wolf inside him, and Michelle Pfeiffer’s Morose Pixie Dream Woman he simply tells her exactly what’s happening to him, with no thoughts of trying to conceal the truth like other films might waste time with. She accepts it, with thoughts of supernatural never coming into the dialogue and the chemistry between the two actors as they play this material is palpable, unexpected in how it comes off. Elaine May reportedly worked on the script (credited to Jim Harrison and Wesley Strick) and the recognizable sharpness of her dialogue brings the drama into focus so it pops for much of the first half even during the small moments like the dryness of Ron Rifkin’s doctor or how Will is continually trying to talk his way around what’s obviously happening, looking for some sort of rational explanation that “medical science has overlooked”. The bulk of his drawn out visit to Om Puri’s Dr. Alezais is almost too sedate in comparison blatantly laying out the themes in a way that feel designed to get people to check out of the film for a few minutes. Maybe Dick Miller’s Walter Paisley from THE HOWLING wouldn’t have been such a bad idea here (Nicholson and Miller together would at the very least be a cool Corman connection) and while WOLF definitely gets points for taking the serious approach, it that sense it doesn’t always have the right maverick sensibilities to fully click.

It’s an understated, mannered film about a world that is beginning to burst apart at the seams but no one reacts to such changes with anything other than mild puzzlement, another element that removes the events from horror movie logic—the matter of fact response by David Hyde Pierce (FRASIER had just completed its first season when this was released) to Will no longer needing his glasses and the cop played by David Schwimmer (right before FRIENDS premiered) more concerned about his handcuffs than the impossible event he’s just witnessed happen. Even the police investigation during the final third as Richard Jenkins’ detective comes to the hotel room to inform Randall of the brutal murder of the wife who has been having an affair with a younger man (yet more shades of O.J., even if the reality of that event doesn’t quite match up) is portrayed as dry as possible so the big final showdown between werewolves, a word that I’m not sure is ever spoken, can’t help but seem ordinary in comparison. A widely circulated still not in the film showing Nicholson about to transform while Pfeiffer lays beside him in bed speaks to how low key the approach ultimately became. Once the subtext becomes text and the transformation as actually taken place it’s not as intriguing anymore. But the film’s own curiosity about its themes remains intriguing throughout. Just as Will Randall tries to piece together the truth of what’s really happening to him it’s a film that is always trying to understand what it is and it makes the end result that much more compelling even if it doesn’t always hold.

Jack Nicholson gives an intriguingly low key performance, not only going against the expected but seeming continually engaged, just as curious about how to explore what’s happening to Will Randall as the character is, always holding the reality of the film together. Michelle Pfeiffer makes sense out of what seems to be practically an impossible role, barely a person at all, giving both her co-star and the film a surprising amount of empathy, indicating how she’s just off enough herself to be the right woman for him and it’s maybe one of her most underappreciated performances. James Spader approaches his role as trying to be the uber-version of his familiar yuppie scum portrayal—compared with characters he played both before and after this I don’t know if that quite comes off but it is a nice turn, playing him as an asshole who not only knows he’s one but revels in the mindgames that it entails. Christopher Plummer brings the expected chilly intelligence to his billionaire that balances just enough disinterest in all this publishing stuff to get momentarily amused by the back-stabbing around him while Kate Nelligan as Randall’s wife has kind of a thankless role but she nevertheless kills it in her last scene. Nichols makes something out of the bit roles as well, particularly Ron Rifkin, David Hyde Pierce and Eileen Atkins as Randall’s loyal secretary. Playing a stock investigating cop role, Richard Jenkins becomes an unexpected off-kilter glue for the film in its last half hour, a refreshing link to the real world while the plot gears of the climax have to turn and Elaine May makes an uncredited vocal appearance as a hotel phone operator—hearing her chipper voice immediately after a brutal werewolf attack says about as much about the dual nature of the film, and the approach taken to it, as anything.

WOLF is a film that I still feel an inquisitive fondness for as I continue to try to find my way through it, trying to understand what it is as it fights against expectations. The end result may be uncertain, it may be battling against its own two halves, but it seems fascinated by that battle. The incessant, haunting score composed by Ennio Morricone which provides the film with an undeniable shade of melancholy that I don’t think is present otherwise feels like a part of that battle as well. But melancholy for what—for Will Randall? For the unexpected romance between the two leads? For revisiting this film 20 years later? It’s about a lot of things that don’t exist anymore, whether the idea of a summer movie aimed at adults, a portrayal of a New York media world that I imagine would be somewhat different now or just people in the world in general. Maybe it’s a reminder of what things were like for a brief period back in the early 90s. One of the final images of the film indicates that the transformation we’ve been witnessing for the past two hours is now complete. If a similar transformation began within the world we live on June 17 1994, I can’t help but worry that we still haven’t witnessed the end of that particular metamorphosis.

Thursday, June 26, 2014

A Very Accurate Word

Quite a few years ago, longer than maybe I’d care to admit, I went to my friend Dani’s birthday party in Griffith Park one afternoon. Because Dani always had a knack for doing this sort of thing at his events part of the day involved him pairing people up together so they could go off by themselves to various corners of the park and, well, analyze each other. Take my word for it, if you knew Dani this wouldn’t seem at all odd. I was paired up with a woman I’d never met named Jill Soloway and in all honesty much of what we talked about has long since left me but I do remember that our conversation was intense, satisfying and somewhat cathartic. If I had known then that she was going to go on to be one of the main creative forces behind one of the best television shows of the aughts, SIX FEET UNDER, maybe I would have written some of it down. I also probably would have tried a little better to stay in touch with her, but never mind. All this time later I still run into Jill Soloway in random places every few years and get a vague look of recognition on her face which is better than nothing from the writer of the “I’ll Take You” episode of SIX FEET, I suppose. After working on several other series through the years including UNITED STATES OF TARA and DIRTY SEXY MONEY, 2013 saw the release of Soloway’s first feature film as director, the unexpected and piercing AFTERNOON DELIGHT for which she won the Best Director award at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and was also named by no less than Quentin Tarantino as one of the best films of the year. A comedy that always remembers to keep genuine emotions in mind, a character study which never holds back on all the flaws of the people in it, it’s a brave and admirable piece of work. That it’s mostly set pretty close to my neighborhood makes it that much more interesting for me, set in a world that I recognize but am not really a part of, fitting since it’s made by someone who I’ve met but can’t honestly say I know.

Upscale Silverlake wife and mother Rachel (Kathryn Hahn) is feeling listless in life with her one child no longer a baby and husband Jeff (Josh Radnor) focused more and more on his app-heavy business with even sex between the two of them not really happening anymore. After a trip to a strip club with some of their friends to spice things up where Rachel is given a lapdance by a stripper named McKenna (Juno Temple) she can’t get the stripper out of her mind and manages to figure out a way to meet up with her again. One thing leads to another and once McKenna finds herself in a jam Rachel brings her home to stay for a few nights until she finds a place to stay. Soon enough Rachel learns that McKenna isn’t just a dancer but a full-fledged ‘sex worker’ as she calls it leading to things becoming even more complicated when McKenna inserts herself into the lives of some of Rachel and Jeff’s friends as well.

“A job does not define who you are,” says Rachel at one point to defend stripper/‘sex worker’ McKenna, leaving it unspoken that she can’t define herself anymore and is drawn to McKenna in some sort of friend/protector/mother/lover combo that she can’t come close to putting into words. Feeling rudderless as she watches life go on outside of her like the car wash she goes through in the first scene, she’s trying to change her own narrative without knowing why and she can’t even find the correct lies to explain what she’s trying to do with McKenna, let alone the actual truth as if she’s wondering, If I don’t feel like myself anymore, can I be someone else? Almost never willing to let a laugh go by without adding an extra layer to the moment, AFTERNOON DELIGHT takes the inherent gimmickry of its story and turns it into something genuine and honest, not going for the easy laughs that you’d expect from a movie that contains the line, “The stripper is in the maid’s room?” while also resisting the obvious melodrama that could occur. When Jill Soloway appeared at a Cinefamily screening of AFTERNOON DELIGHT this past January as part of their Underseen & Overlooked of 2013 series during the Q&A afterwards she talked about how the likes of John Cassavetes and Hal Ashby had been influences on her in making the film. Other directors including Paul Mazursky come to mind as well which might just be me pigeonholing the film as a Silverlake-set DOWN AND OUT IN BEVERLY HILLS with a sex worker (even Josh Radnor’s app invention is like a modern day equivalent to Richard Dreyfuss’ coat hanger business) but regardless such comparisons manage to make AFTERNOON DELIGHT even better, revealing just how much it fits into its own world combing its influences with the unique style of its writer-director and a tone that fascinates me even more.

It takes what would be just the expected laughs that turn up throughout and goes deeper, aware that these characters feel certain things that they don’t know how to put into words, they all have fucked up feelings that they don’t know how to express. AFTERNOON DELIGHT is compelling and alive while also possessing a tone that allows it to be its own thing with a script that is tight and to the point yet always loose enough to explore the characters, to remember that more than anything it’s about those characters. It respects all of them, even the ones who seem like mere caricatures at first, and yet knows that it can only probe so deeply to find out the real secrets, learn what isn’t being said. The interactions never feel easy and the film is much more interested in exploring the faces seen in the Cassavetes-like giant close-ups of her actors than in turning it all into one giant farce, particularly during the extended women & wine sequence where Rachel completely breaks down in front of her so-called friends. An up close connection to McKenna’s world also turns out to be a step too far for Rachel, not as cool for her or as potentially hilarious for us either leading to the undeniable discomfort that can be felt when things go wrong. You can never be certain how much you’re going to get to know some people. Sometimes you realize you didn’t know them at all.

It’s a film about connections natural or forced, in general or at this specific point in time and fittingly the first word we hear is an automated voice stating “connection”--the film being very much set in a world of Twitter and apps and blogs (“Name one good thing that’s come from blogging,” Jeff the app inventor dismissively states) that isn’t secondary to its main concerns as much as a believable acknowledgment that it’s how we’re living right now, particularly in the way Rachel describes her present day existence as being “online” and nothing more. The dialogue throughout is razor sharp and as much as it does feel like a film made by a writer willing to allow a certain amount of improv from the actors Soloway continually displays not only a director’s eye but also a soul that causes her to care for all of her characters. She makes use of the space in the architectural beauty they live in, placing the characters opposite each other in the frame but also with an eye for the little details sprinkled throughout, the quick shot of flies on lox as a brunch party dies down, the look on Hahn’s face as she lies in bed post coital while Radnor collects some change from the side table. That particular shot is a sly, subtle illustration of how much it feels very much about the female point of view while still being very aware of the men around them shrinking into beta maledom—in this film it’s the guys who hug when greeting each other, not the women. Even the deleted scenes on the DVD reveal bits that would have brought out such details if they had remained—one particular shot might have been my favorite moment in the entire film if it had stayed in.

Maybe this particular subgenre, if there even is one, could be termed Silverlake mumblecore along with some SIX FEET UNDER that’s certainly in its DNA and the details feel right, whether the presumably ad-libbed dialogue talking about my favorite local taco place or even the radio in Rachel’s car that’s tuned to KCRW because, well, of course it is (speaking of which, the soundtrack is very KCRW-friendly in all the best ways). Even if I’m not in a place in life to relate to all of it the characters and their world feel continually real, they feel like people, fucked up as they might be which makes something like the reality disconnect in Judd Apatow’s THIS IS 40 all the more plain. That film has an angry encounter with fellow parents as well only in that case the ultimate goal is basically wacky improv whereas in AFTERNOON DELIGHT it strips away the stereotypes to the point where we can’t judge them so simply anymore. The well-off lives of Rachel and Jeff crossed with her own uncertain sexual obsession brings Blake Edwards’ “10” to mind as well—ultimately McKenna is about as much of a blank for Rachel as Bo Derek is for Dudley Moore and in both cases the hoped for connection turns out to be something very different. AFTERNOON DELIGHT could have been played as straight comedy (it certainly still qualifies for the term) and nothing more but it digs deeper, exploring what’s really going on under the skin of the characterizations. Even Jane Lynch as Rachel's therapist, which almost seems like the sort of role you can fill in yourself, plays as much more earnest and genuine in addition to her ultra-sharp comic timing (plus the way Jane Lynch says ‘quinoa’), than you would expect. The film doesn’t answer certain questions and stays in my brain longer as a result. The final shot feels like the most perfectly natural place to leave it on, a feeling that the lead character has genuinely earned, showing us who the movie is about, what it took to get to this place and how much the feeling really matters.

Kathryn Hahn (who, if I’m going to be honest, has ranked third or fourth on my list of pretend girlfriends for some time) has already proved herself to be that sort of actor who can effortlessly go between comedy and drama and here she’s phenomenally brave down to the little physical touches, bringing every palpable ounce of Rachel’s own daily awkwardness to life. Juno Temple balances between showing us just enough of McKenna to flesh her out and yet still keeping her an enigma, playing moments in ways that seem specifically designed to throw the other actors off balance while keeping the character totally unapologetic and refusing to allow the film to judge her. Temple is absent from the chummy DVD audio commentary between Soloway and Hahn which feels weirdly appropriate as if it keeps the actress an enigma as well. Josh Radnor plays the distracted puzzlement around the whole situation just right, giving him the chance to show more range than he was ever able to do on HOW I MET YOUR MOTHER and when he finally lays in on Rachel about whatever she’s done he does a great job. It’s a terrific cast all around—Michaela Watkins has been a secret weapon in various films and TV shows lately and here she continually adds layers to what at first seems like simple comic relief while Jessica St. Clair has a completely effortless style as Rachel’s best friend. John Kapelos, familiar from many credits including THE BREAKFAST CLUB is one of McKenna’s clients, balancing the tightrope between sleaze and just a guy who’s perfectly happy to pay for her. Correctly, the movie doesn’t judge him either.

Near the end of the DVD audio commentary Soloway and Hahn talk about the film playing at the Los Feliz 3 which was actually where I saw it. Just another reminder that it’s a world I partly recognize and that I hope there are more films to come from the director in this oddly personal Cassavetes-Mazursky-Edwards vein. And it hasn’t escaped my attention that this is a film featuring strong female characters written and directed by a woman—that fact should be more incidental than it is in 2014 but unfortunately I suppose it still isn’t. If someone is going to create roles this good for someone like Kathryn Hahn not to mention other underutilized actresses out there like Illeana Douglas and Lisa Edelstein it might as well be her. Right now she’s producing a series for Amazon that she created entitled TRANSPARENT and the way things are now in getting films made I can’t say I blame her but, regardless, Soloway is a voice that I hope we get more films from. I hope some of them are set in Silverlake too. At its best AFTERNOON DELIGHT is clever and funny but also intense, satisfying and somewhat cathartic. Just like that long ago day in Griffith Park. And this time around, I know that I’ll remember it.

Saturday, May 31, 2014

Look How Far It Got You

Even if I don’t hang out at Ye Rustic on Hillhurst anymore or go to various parties throughout Silverlake with the same people I still see some familiar faces from those days every now and then. There’s one woman who I don’t see much at all beyond the odd Trader Joe’s sighting but I know she has a kid now, a few years old by this point. Looking at photos of her on Facebook I see a different person than I knew, or at least thought I knew back in the days when I couldn’t imagine anyone ever seeming more deadpan in life than she was. We were never close but I suppose thinking back on it now she’s one of those many people who pass through your world that you only ever know slightly but still think fondly of. People who show up in your life for little more than random appearances wind up making an impression. So I guess because of that whenever I look at Sarah Polley’s unpredictable, enigmatic, take-no-shit character in 1999’s GO I’m always reminded of that woman. It makes me think that much more fondly of the film as a result. Even though it makes no sense, it makes me think that much more fondly of her too. People are unpredictable. You didn’t know them then. You don’t know them now. You never will.

Written by John August and directed by Doug Liman, GO turned 15 this year, released in April 1999. Looking back, I think of that period as being a pretty carefree time in my life but that’s a lie. I know that I was worried about lot of what was going on. For one thing, NEWSRADIO was canceled right around then. Probably other stuff was happening too, but never mind. That’s what memory does. Enough time goes by, you’re not sure what really happened anymore. I’m still not sure about a lot of things. GO feels like a part of that time for both me and films that were released then, an offshoot of the effect Tarantino and PULP FICTION had on the world but it manages to siphon off the correct elements from that film to go correctly with its own particular style, coming up with its own overall tone in the process. There’s not that much of a story and not very much is resolved in the end to come out of that slight story, giving the whole thing a no consequences, live-to-rave-another-day vibe. The film just happens to be set on one of those days.

It’s the Christmas season in Los Angeles. Supermarket employee Ronna Martin (Sarah Polley) is behind on her rent and takes over the shift of Simon (Desmond Askew) who is going off to Vegas for the weekend with his ‘mates’ (Taye Diggs, Breckin Meyer, James Duval). The sudden appearance of actors Adam and Zack (Jay Mohr and Scott Wolf) looking to score off Simon leads Ronna, accompanied by friends Claire (Katie Holmes) and Mannie (Nathan Bexton), to seek out Simon’s dealer Todd Gaines (Timothy Olyphant) for a favor. But circumstances cause Ronna to try to pull one over on Todd which leads her to an even larger plan to score some more quick cash at the big Christmas rave happening that night. Meanwhile, Simon, who’s using Todd’s credit card, is off on his own adventure in Vegas involving a mishap on a strip club while Adam and Zack are trying to make good with the cop Burke (William Fichtner) they’re working undercover for but it turns out he has yet another agenda in mind for the evening.

The use of the Columbia logo at the very beginning of GO as it blends in with the sounds of a rave over the opening credits perfectly encapsulates the approach of the film, how things are always unexpectedly moving forward before you’re fully prepared, not quite knowing what’s ahead, not taking a moment to think of the consequences. During the period of the mid-to-late-90s when films trying to be in the Tarantino vein went way too overboard on the snarky violence GO walks a tightrope that keeps its tone somehow blithe and effortless. It’s funny but not snarky, edgy but never too nasty, always active and energetic. So much of the film looking at it again now remains enjoyably off-kilter and unpredictable in the very best ways right from the start, its propulsive style keeping things moving no matter what through every beat of the sly, offhand dialogue punctuated by the occasional out of nowhere burst of intensity. Even if things wind up not turning dangerous there’s always the feel in the air that they can.

A slicker, more plot-driven look at the scuzzy end of L.A. nightlife than the Liman-directed SWINGERS from three years earlier, the go-for-broke vibe the director brings to GO along with the AVID hiccups in the cutting style provided by Stephen Mirrone (who won the Oscar for editing TRAFFIC not long after this) is always well-executed, always with a purpose. The way August’s script crosses from one of the stories to the other, hip-hopping around the timeline, feels totally effortless while maintaining a loosey-goosey approach to its plotting that feels somehow correct—there’s a reason why Adam and Zack show up at the rave and it’s a funny one but still pretty irrelevant in the end and even the way two characters during the Vegas section are sidelined almost immediately from food poisoning (“I told you not to eat that shrimp”) adds to that unpredictable feeling as if even the film is a little surprised by who’s about to take center stage. Even the digressions, more than a few of them involving Nathan Bexton’s Mannie, feel totally a part of it all because if this film can’t have a digression involving an imagined conversation with a cat, what film can?

The non-linear narrative approach dividing the three sections felt very Tarantino at the time, even if he wasn’t the first to do that and the dark comedy, offhand violence as well as the handful of pop culture references (that the film never explains a certain Omar Sharif joke makes it funnier) certainly add to that familiar feeling but never takes it to such a dark place that would seem wrong for the material, threatening to go as far as some movies from that period did but not getting there because no one in it is really capable of those kinds of actions anyway. Their lives aren’t even fully real yet, like the story Taye Diggs’ Marcus is being told by Breckin Meyer that actually happened to him. Some of the characters are likable, some are idiots, some of them are clearly trying just a little too hard to seem like something that they’re not and more than a few I would never want to ever meet but the film has an affection for all of them, misplaced as it sometimes might be. And as loose as it might feel at times there is genuine skill evident in Liman’s direction with a point-of-view that always feels present, adding to the danger and dreamlike feel. There’s a skill to how he approaches each scene in the staging that stands out now, always making this world feel that much more filled in He even handles the repetition in the overlapping correctly. Looking at the film from all this distance now it occurs to me how the age gap between some of the characters makes the film caught between the vibes of Gen X and Gen Y, even if that specific term hadn’t been coined yet, which goes perfect with the off-kilter vibe. The film’s one real ‘adult’ (a strip club owner, of course) is left outside of all this with nothing to do but complain about how the world’s become a place where people get ahead just because of someone else’s incompetency. GO doesn’t see anything wrong with that. Its characters aren’t aware, at least not yet, of the alternative.

Along with the PULP FICTION vibe it’s also a little like the brief gangbanger scene from Liman’s own SWINGERS taken to feature length and the similarities to that film (including a similar poster; no shared cast members though) make them complement each other in intriguing ways. They not only both have 818 jokes—the one in SWINGERS is better, but no big deal—they each take a side trip to Las Vegas that runs close to a third of the running time. Unlike SWINGERS, Vegas in GO feels like its own world somehow cubed—nothing really matters and you can do anything you want, steal a car, get in a car chase, fire a gun, and there are no consequences. With the lives of everyone in it feeling somehow temporary, heading towards a destination that is uncertain, there are no real consequences in GO either. It’s not that kind of film. At a certain age, on a certain night, even if you’re almost in a car crash you sometimes never quite pay attention to those things. GO is minor but it seems ok with that. It has a first film feel, even if it wasn’t Liman’s first film, but it has the right energy to culminate in the ‘surprises’ that Claire talks about in the brief flash-forward that opens the film. It has a life to it all, even down to the winding down hungover feel of the last ten minutes when two characters unexpectedly sit down to breakfast. And it’s strangely optimistic too with the one totally selfless, honest action that happens between two people who never fully know what’s going on. Things are unexplained, then moved on from before they get fully clarified. “Girl in ditch, our problem. Girl out of ditch, her problem,” says Jay Mohr’s Zack to Scott Wolf’s Adam to clarify their position in things when they’ve gotten out of their jam. There’s only so much you can do, so far you can go, in just a few seconds. You do have to deal with your own problems before the sun comes up, after all. Even at the end, the final shot creeps in closer to the location for no particular reason but doesn’t pause. No point in stopping. No point in ever stopping.

It’s a film containing multiple performances that make me want to say, “Well, that person steals the show.” Sarah Polley seems to have left acting behind by now and I look forward to whatever she’s up to next but her work here sets the film apart more than it would have otherwise. She doesn’t have a dull moment here, there’s not a single gesture or inflection in her voice that doesn’t add to her characterization in some way. Frankly, the only thing wrong with the film, as fun as it is, is not only that Ronna isn’t in it the whole way through but that we didn’t get more films with this character—it’s a combination of character and performance but more than anyone else in the film I want to know what her story is beyond the film. Just her body language in a late scene as she limps her way through the supermarket again says so much and it’s a performance with an energy that feels completely daring. Katie Holmes, who seems to play every scene wondering what she’s doing there, matches up well with her as the presumably more straight-laced Claire as does Nathan Bexton who spends pretty much every moment he’s around blissfully unaware of anything around him.

Timothy Olyphant is particularly strong, without a line or reaction shot that is quite what you’d expect it to be while straddling the divider between sharp comic timing and a genuine sense of danger. Desmond Askew’s cockiness is continually enjoyable while even though there doesn’t seem to be much to Taye Diggs’ character on the page past his speech about tantric sex he brings his part a sly intelligence that mixes well with his co-stars. Jay Mohr and Scott Wolf play off each other just right as the bickering couple caught up in one thing after another on this night and this section still plays as a little progressive. Plus there’s Mohr’s mangled pronunciation of ‘bouillabaisse’ too. The unpredictable behavior of William Fichtner during the would-be drug bust and later on opposite Jane Krakowski at that early Christmas dinner adds a whole other element of nervous comedy to the film and I especially love the unexpected intensity in Krakowski’s eyes when she insists on how fast they’re climbing on the Confederated Products ladder. J. E. Freeman is the calm of the entire film as the pissed off strip club owner in his speech about how you get to the top in this world and Melissa McCarthy turns up in what looks like her first feature appearance showing how you absolutely nail a role with less than a minute of screentime.

GO is a movie that reminds me of possibilities that were once there. It resists the darkness. Maybe it was easier to do that in those days. There is the L.A. centric nature to it, as well and as someone who lives right near a JONS but always goes to the nicer supermarket slightly further away I will always have a fondness for how the crappy supermarket is named SONS with the correct sort of lettering in the sign. It reminds me of how freaky things can be, that feeling in your twenties where, just thinking you’re going out for the night, you can find yourself in a strange apartment somewhere almost before you know it. Of how you can do something stupid but you’re young so, well, what’s the worst that can happen? When I think about how young I was when I first came to L.A., how stupid I was, it scares the hell out of me. I never did more than wander through a rave-type atmosphere once or twice (Since I’ve never done ecstasy or most other drugs either, how accurate is all how the movie portrays it? Beats me) but there’s an authenticity to this world. Ronna being so young, another piece of her backstory I wish we could know about, actually also reminds me of another girl I knew way back when, who was probably also way too young to be living on her own the way she was and I suspect may have had a few nights like this one that I was never privy to. She’s elsewhere now, also with a kid incidentally, and I think she’s happy. I hope she’s happy. It’s not 1999 anymore. Things change.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)