Thursday, March 29, 2018

You Do The Math

The 20th anniversary of DEEP RISING has already come and gone so it might not be too necessary to spend much time contemplating that particular milestone. More important things happened back in ‘98, after all. Maybe. It’s been a long time. But I saw this film back then so I may as well put some thought into it. Released at the very end of January (opening in eighth place; TITANIC was still going strong), DEEP RISING was an early film written and directed by Stephen Sommers who immediately after its box office failure went on to the blockbuster success of helming the first two MUMMY films with Brendan Fraser which were then followed by VAN HELSING in 2004, a film I had such a negative reaction to that immediately pledged to not see anything by him ever again. Considering his one wide release since was 2009’s G.I. JOE: THE RISE OF COBRA that hasn’t been a problem. But I lived in blissful ignorance of these future events back when I kinda sorta enjoyed DEEP RISING on opening weekend (after which I snuck into the Barbet Schroeder thriller DESPERATE MEASURES, which might be even more forgotten now) and, in fairness to Sommers, I also remember genuinely liking the version of THE ADVENTURES OF HUCK FINN that he directed for Disney in ’93. As for DEEP RISING, looking at it again on the Blu-ray release that pairs it with the 1994 Heinlein adaptation THE PUPPET MASTERS, it’s not bad, maybe just good enough to go perfectly fine with a night of pizza and beer. It pretty much does the job with enough promising touches that you wish maybe, just maybe, it could have been a little better. It’s no big deal that it isn’t but sometimes you can’t help but wonder.

In the middle of a storm in the South China Sea, John Finnegan (Treat Williams) along with crew members Joey Pantucchi (Kevin J. O’Connor) and Leila (Una Damon) is piloting his boat with a charter of mercenaries led by the mysterious Hanover (Wes Studi) to an unknown location. Meanwhile somewhere nearby, the mega-deluxe cruise liner the Argonautica is in the middle of its maiden voyage with owner Simon Canton (Anthony Heald) lording over the festivities which is quickly followed by passenger Trillian St. James (Famke Janssen) being caught red handed breaking into the ship’s vault and thrown into a makeshift brig. But just as the ship’s navigation and communication systems are mysteriously disabled and an unseen threat to the ship begins causing mass chaos and destruction. As Finnegan begins to realize that his own passengers are intent on attacking the Argonautica themselves to loot and destroy it, they arrive only to find it seemingly empty with no idea what has happened until creatures beyond any comprehension quickly begin to make their presence known and are preparing to attack.

It’s basically THE POSEIDON ADVENTURE meets BEYOND THE POSEIDON ADVENTURE with the added presence of underwater ALIENS-type creatures on the attack and, I have to say, I’ve heard worse ideas. DEEP RISING is slick, glossy, loud and gory with just enough mayhem to keep things moving while still making me wish that there was a little more of a plot to it all to keep my interest. Of course, since it’s never really meant to be much more than a monster movie that probably sounds like I’m just looking for something to complain about. Which is fair enough. With a good amount of energy and snappy dialogue it’s more of an energetic theme park ride than a horror film but since it knows what it wants to be the tone is consistent, always knowing to have one more joke standing by to keep us off guard. Although I haven’t seen Sommers’ THE MUMMY ’99 in years my very distant recollection is that the two film’s plots are surprisingly similar, featuring two opposing groups forced to team up against an otherworldly force to stay alive, with DEEP RISING the gorier, R-rated version of the storyline even if it is mostly CGI gore, one nasty axe to the face notwithstanding. And it’s always aware of the film it’s trying to be with a healthy sense of humor that almost makes you forget that there isn’t quite enough going on from scene to scene.

Part of it is an odd structure, one that jumps into the action almost immediately while still taking way too long to get all the necessary pieces into place, a little too much wandering around the mysteriously empty boat during the first half before the various factions finally collide. The lengthy buildup means that Williams and Janssen, the alleged lead couple, don’t even meet until close to the halfway point and there’s not enough of a chance for their relationship to develop into much beyond the first glance. It’s a film that too often doesn’t realize which elements are working so it winds up focusing on the wrong things, particularly the amount of time spent on the mercenaries who are mostly all dull meatheads with some sort of Chinese-made superguns that fire endless rounds of ammunition which keeps the focus on them instead of the Howard Hawks-styled banter between the leads which gives the film much of its personality.

Played by Treat Williams, Finnegan is given a simple “Now what?” as his default catchphrase and his snarky impulsiveness is about all we ever know about him, part Han Solo and part Bogart in TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT which I guess means that Kevin J. O’Connor is playing Walter Brennan and Famke Janssen is supposed to be Lauren Bacall but the fact that I’m even making these comparisons really means that I’m trying to will this film to somehow be better or at least become the film that I can sense lingering underneath all the noise. That’s how much I want to like it with the personalities of the leads giving me hope but it never quite gets there, too often more interested in getting to the action and gunplay.

Just about the biggest plot thread in the film, the mystery of who’s responsible for the sabotage of the ship, is done away with in about a minute of screen time, so fast that one of the characters is forced to comment on the plot expediency but when the culprit offers the feeble excuse, “I misjudged the market!” for his financial reasoning it might be the best line in the film. Since almost all of the hundreds onboard the ship are killed off right away (they’re mostly rich people, so who cares) the main cast feels slightly underpopulated and maybe could have used an extra character or two to add to the disaster movie vibe, plus any film that so quickly tosses out the concept of Famke Janssen as cat burglar isn’t one that I can bring myself to completely endorse (this is as good a place as any to admit my weakness for Famke Janssen, just to state for the record). With a film like this, scares count as well as the laughs and even the gore effects but if the characters don’t stick in the brain the way they do with the best of them whether ALIEN or Carpenter’s THE THING, it’s all going to dissolve and DEEP RISING only gets part of the way there, coming up a little short when it comes to its own personality to help remember any highlights five minutes later, let alone twenty years.

If anything it’s playful, maybe as playful as a film about monsters that suck “all the fluids out of the body before excreting the skeletal remains” can be with Anthony Heald gravely informing us of all the horrific possibilities of what they can do since he’s clearly read up on them somewhere intoning, “They drink you,” in order to drive the point home. The basic look of the creatures which were created and designed by Rob Bottin isn’t bad, leading up to the reveal of the Alien Queen-like big monster, but twenty years on the film is a reminder of that point in the digital revolution still just a few years after JURASSIC PARK when there was still a lot clearly done on set instead of green screens as it’s done so often today so the film looks expensive—and with all that water, this doesn’t seem like it was a fun shoot—but the creature effects are mostly if not all done with CGI so they feel separate from the other elements, coming off as a little too cartoony and weightless so the actors never seem like they’re interacting with a creature actually in the room. A few times it even plays like there was scrambling in the editing room to cobble something together where the effects shots simply weren’t there and while the monster gore effects depicting the after effects of the “drinking” that we’re told about aren’t bad it’s hard for me to ever think of digital effects work like this as scary or disturbing. To the film’s credit, it never allows those effects to completely overwhelm everything else going on like they would in Sommers’ later films and the film at least tries to keep the focus on the human leads as much as possible even if the material is sometimes lacking. As an aside, the sound mix on the Blu-ray keeps the dialogue levels normal but the endless streams of gunfire are LOUD which means I keep having to turn the volume down so the film clearly doesn’t care that I’ve got neighbors. Not to mention that even when a film is meant to be a non-stop thrill ride about deadly creatures chasing you, sometimes the quiet moments help.

In addition to all the mayhem there’s the Jerry Goldsmith score which fortunately contains a little more flair than the standard action beats he was sometimes composing around this period, so even when it sounds familiar as chase music that we’ve heard before but it still raises the film up immeasurably. It’s all a reminder that there was almost no one better to almost make us think that the movie was actually as good as his music made it seem, so rich and evocative that it makes me think damn, this is what movie music is supposed to be. There aren’t too many composers like that these days. With dialogue that ranges from enjoyably clever to Treat Williams saying, “I have a very bad feeling about this,” DEEP RISING has a slickness and never gets too heavy, always moving relentlessly to the next scene and even though I keep wishing that it wouldn’t be so loud or stupid and even if the climax goes on way too long like way too many films do, more than not the action beats are just right. The banter between the characters who are left during the very last scene almost offers the impression that there was more during the film then there actually was but at least it’s fun and energetic which these things aren’t always. All that action and monster mayhem at least reminds me every film that tries it doesn’t necessarily pull it off. It could have used more personality but what’s there is at least something so to get close to the Hawksian lingo that the movie sometimes strives for, it’s almost good enough. That can help get you through those long nights of beer and pizza too, because the next film you put on with a nearly identical plot might not get anywhere near this close.

The cast helps too, with Treat Williams’ lightweight personality mixing perfectly with the tone and he gives things just the right arch sense of gravity as the monsters attack. Famke Janssen brings a sharp canniness to her role, playing it as if there isn’t much that doesn’t amuse her until she finds out what’s really going on but she’s not even too phased by that as long as there’s a chance to get away and in the moments she’s given with Williams the two play off each other just right. I still want to see her in a full movie where she plays a jewel thief, though. Kevin J. O’Connor, who went on to appear in a few other films for Sommers but more importantly in THERE WILL BE BLOOD and THE MASTER for Paul Thomas Anderson, clearly knows that he’s the character who gets to steal as many scenes as he can and he goes for it, bringing a full characterization to what’s merely supposed to be the comic relief. Anthony Heald as the ship’s owner takes his smarmy Dr. Chilton persona to the most extreme as he explains the intricacies of what these creatures are while the likable Una Damon, a ubiquitous presence during ’98 between this, DEEP IMPACT and THE TRUMAN SHOW, work so well with Williams and O’Connor that I wish she could stick around longer. As tiresome as all the mercenaries quickly become, Wes Studi as the leader gives an added gravity to things purely from the vibe that he obviously has no interest in the monster stuff or any jokey quips and is ready to stare down anyone who looks at him wrong. The other guys in his group include Cliff Curtis, Jason Flemyng and Djimon Hounsou in a minor role filmed before he starred in AMISTAD but released a month later.

DEEP RISING was released by Hollywood Pictures, the Disney division active at the time with a logo that now seems like a true relic of the 90s, sort of like how the film itself now feels like an artifact of the sort of movies that we seemingly got in theaters weekly back then. And I’m not entirely sure why I’m writing about this movie since the presence of Famke Janssen alone doesn’t justify it unless it’s that milestone of twenty years and thinking about where I was in life back then, how different I was. Maybe not that much. I guess I’m remembering it as part of a time when things seemed more carefree, whether they should have been or not, when I would see movies in the middle of the day in no rush to go anywhere else. I probably just assumed that was going to last forever, just like DEEP RISING has a story that instead of ending just sets itself up for the next chase. The idea of living in a monster movie that never ends doesn’t sound so bad as long as I’m one of the survivors, even if it is a monster movie that’s more interested in running from the monsters than in finding out anything about them. But in the end, I don’t think DEEP RISING is about anything more than running away from monsters towards more monsters, anyway. I guess it’s just a version of that movie which manages to stick in my brain more than others, a sweet spot of one the kind which has a lot of things that appeal to me but maybe falls just short. It’s still one that I sort of enjoy regardless. As for how much I’ve changed since then, maybe a movie with a giant underwater monster is the perfect way to avoid thinking about it. With luck you can forget about those things for a few seconds longer before being forced to return to the real world.

Wednesday, March 14, 2018

Played From The Inside

The reasons don’t matter. All you have is the pain. You feel it down to your bones and it never leaves you. Whatever connection that was once there is severed. Sometimes in the middle of the sadness you remember the laughter, emerging from a memory of one of those days in private moments that seemed to go on forever and you wish more than anything you could have that feeling back. The laughter of the one who went away.

The Mike Nichols film of HEARTBURN came out in late July 1986 and it’s not exactly what we think of as a summer movie anymore but it did open the same day as Stephen King’s MAXIMUM OVERDRIVE so I hope somebody did that double feature in a multiplex somewhere. Based on Nora Ephron’s novel and directly inspired by her marriage to Carl Bernstein and how the discovery of his affair while she was pregnant led to their divorce, maybe some of the details were altered for the fictional retelling in the book but they were certainly changed for the film; part of the divorce agreement stated, for one thing, that the character based on Bernstein in the film could not be presented as anything other than a loving father when it came to his children. Mike Nichols even served as legal signatory, so this was not just any dissolution of a marriage. This was one that got a movie, directed by someone who was already closely attached to the situation with Ephron writing the script herself, following up on co-writing SILKWOOD for Nichols a few years earlier. And one where, because of his direct connection to the people involved, it was made by someone working in a world that he knew intimately. More than most films, HEARTBURN is a product of the people who lived what happened. The pain is tangible and the jokes have a sting to them, even if it still feels like some blanks haven’t entirely been filled in.

Food writer Rachel Samstat (Meryl Streep) meets well-known political columnist Mark Forman (Jack Nicholson) at a wedding where they are instantly drawn to each other. In spite of her initial reluctance they soon marry so Rachel moves with him to Washington where they purchase a Georgetown townhouse, she quickly joins his circle of friends and becomes pregnant. All is well when the baby is born and Rachel doesn’t waste any time getting pregnant with their second child but it all shatters when she discovers Mark’s infidelity with a D.C. socialite. She leaves him immediately, heading back to New York, knowing he’ll follow soon enough and she needs to figure out whether she’s going to forgive him or if such a thing is even possible.

The upper class DNA of HEARTBURN is undeniable, offering a clear view of that New York-D.C. corridor of dinner parties and lunches with fellow media types and complaining about availability of bagels in Washington. An early moment of Streep and Nicholson kissing in front of Cinema I as a showing of MEPHISTO lets out captures that exhilaration of new love found in the perfect place in the world, a world where to have lunch with someone is to know them. To be there is to exist. HEARTBURN probably wouldn’t even be ranked in the top five of Mike Nichols films but it feels like more than any of them he understands every single person in it, down to the extras, that 80s New York which seems so distant now. Along with a preponderance of long takes and even a few cast members it’s hard not to think of the Woody Allen aesthetic from this period as well. A recitation at the wedding where the two leads meet can be heard with the speaker using the phrase ‘love never fades’ as Streep’s Rachel Samstat tears up to the sentiments while Nicholson’s Mark Forman sitting elsewhere is on the verge of falling asleep. The directing credit for Nichols appears over his zoned out expression and HEARTBURN is like a feature length rebuttal to the very idea that love doesn’t fade. Of course love fades. There are times when it has to, whether you like it or not. And no matter how much you cling to what was there, if it’s gone it’s gone.

What HEARTBURN has in addition to the performances is a laid back vibe with an array of clever and insightful dialogue which for a while displays no serious concerns beyond the various friends lounging about on vacation talking about nothing much at all or just the simple glory of Jack Nicholson explaining the plot of THE BRAIN THAT WOULDN’T DIE to Meryl Streep. It’s the sort of film that maybe I’d overrate slightly in memory just because of the people involved, remembering it as an amusing comedy of manners but maybe it isn’t quite substantial enough. It’s a lark of neurosis about two people, each with a marriage already behind them, old enough to be wary of any sign that they’ll fall for someone but just as open to the possibility and even when Rachel gets such a case of nerves that she can’t come out of her bedroom for her own wedding it’s nothing to get too upset over. The sight of them eating pizza late at night and singing songs to each other while celebrating her pregnancy gives a looseness to what we know are the good times with genuine chemistry between the two, a feeling of joy that gradually turns into a bitterly enjoyable exercise of a film, at times more a series of bits where actors play off each other in small moments which is still amusing in itself.

It’s a film about nitpicking whether it has to do with the inability to get their house finished or how in the middle of her therapy session when Rachel tearfully reveals Mark’s affair a few of the other members of the group argue over who brought the chopped liver. That’s life, in the middle of the most dramatic moments there’s always going to be that bickering until that’s just about all there is with nothing left to build on. Ephron wrote WHEN HARRY MET SALLY only a few years later and in some ways HEARTBURN is a proto-version of the broader themes in that film with one famous line that originated in the book of “Heartburn” turning up there instead of this film. Harry and Sally’s jobs matter even less than they do here; Rachel and Mark are both writers which has potential on the surface but never matters very much. The bitter aftertaste that grows is what we’re meant to pay attention to.

Stylistically, it feels like a midway point for Mike Nichols, featuring many scenes shot it long takes but without the coldness of the overly composed anamorphic framings from back during the days of THE GRADUATE and CARNAL KNOWEDGE. The view of D.C. is lightly satirical but it’s still part of the real world with a naturalistic flavor of spring brought to it by Director of Photography Nestor Almendros. More than anything each scene focuses on the actors in the frame, facing them dead on with no distancing technique as if to make us part of their fights but as close as the shots get the answers don’t become any more clear. By this point Nichols’ directorial style has become totally relaxed with an economy to the storytelling as well as the jokes so he never cuts unless absolutely necessary—a dinner party is seen in one shot circling around a table ending on a sight gag that shows how out of place Rachel is, a visual joke that gets me to laugh every time. And her growing realization of what might really be going on while getting her hair done is an expertly done moment, stretching out the denial of the inevitable truth as it becomes more terrifyingly clear by the second.

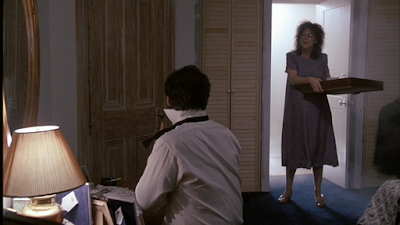

Nicholson’s Mark Forman tossing off a careless “To marriage” as a toast says it all in a blink, unexplained bitterness he’s holding onto that’s growing as he turns his complaints about missing socks into the excuse for where he is all the time. And it’s as if the way he’s using the nitpicking that his wife is such an expert on to fool her is the greatest betrayal of all. But even if there is a reason it still doesn’t matter no matter how much she tries to talk herself into her own feelings while searching for one. I still wish it was more about how the creative edge can get lost if you don’t tend to it and it’s hard not to wonder if even the pettiest of arguments between the real Ephron and Bernstein might have had more teeth to them than what we get here. Maybe because of Jack Nicholson, even if his star power is muted, it makes me imagine the film as something of a Mike Nichols version of THE SHINING, only in this one instead of the writer husband going crazy he just becomes mildly perturbed and uncommunicative while the wife, also a writer in this incarnation, comes at him ready to kill with a desk drawer filled with receipts—Streep emerging from the bathroom holding that drawer might be one of the single best shots involving the combat of two people in a room from the entire second half of Mike Nichols’ filmmaking career.

One other filmic connection might be how the prominent song “Coming Around Again” that serves as the basis for much of Carly Simon’s score appears in the official playlist that recently went with 70mm screenings of Paul Thomas Anderson’s PHANTOM THREAD, another film about a somewhat toxic relationship played largely in close-ups in which food plays a key role. For some people that song with its “Itsy Bitsy Spider” refrain found in the film’s most hopeful moments between Rachel and daughter Annie might be all they remember about HEARTBURN years after seeing it and it’s hard to keep from the song getting stuck in your head, just as the drops of water in that unfinished house representing their marriage and every ounce of tension in it keep dripping down from the leaky roof overhead, as if an incessant reminder that it’s all going to crash down whether you know it or not, whether you admit it or not.

Some of the greatest pleasures in the film are the most offhand like how Milos Forman, whose character hasn’t even been introduced at this point, is placed right in the middle of the shot as the wedding takes place, prominently chewing gum for all the world to see and whenever I see the movie again it’s for these moments more than anything. When Rachel’s therapy group is robbed by a mugger played in his first film by Kevin Spacey (apologies) who followed her out of the subway all the items are placed in a Balducci’s bag, definitely part of the world of lower Manhattan circa ’86 almost as if it’s the side details that really matter, not the foreground which wouldn’t be a problem if the center of it all were stronger. The Jewishness has been bled out (the book’s “Mark Feldman” becoming “Mark Forman” for starters) which makes it feel like we’re missing some of the specifics of the life, the marriage and all the food they eat. Mark Forman is always looking for something he can get a column out of, just as the HBO documentary about Ephron by her son Jacob Bernstein called EVERYTHING IS COPY was a phrase she would use that was passed down from her own mother. Based on HEARTBURN it’s clear that while it’s what she believes it’s also a matter of who she feels is entitled to tell the story.

The book contains recipes to go along with the details that Rachel Samstat reveals about her life, keeping those thoughts in mind almost in a Zen way to concentrate on while other things are falling apart, an element not quite as prominent in the film so I guess the Streep-Ephron combo had to wait for JULIE & JULIA to really focus on the food. It’s certainly there in the film with the crucial use of a key lime pie near the end which in the book played as more of an act of slapstick (in real life Ephron apparently poured a bottle of wine over Bernstein during a dinner at Ben Bradlee’s house) but in the film the moment comes off as totally numb as if the Novocain has permanently been applied. Even the camera angle used for much of the climactic dinner scene doesn’t give us the best vantage point on the action as if to say that the main character is already barely there anyway, not even trying anymore which makes sense but still isn’t entirely satisfying. The film avoids giving any concrete reason for Mark’s cheating with even some pretty good dialogue in the book along these lines going unused but that’s not what the film is about. It still means that there’s a hole where a fully fleshed out character for Nicholson could be but the pain feels genuine so it’s clear that the film believes he hasn’t earned the chance to give his side of the story. It’s not his film. All there is, in the end, is what there was. At a key moment Rachel has Mark tell the story of when she gave birth to their first child but when he finishes, she turns away from him as if to say that from that moment on those memories are for her alone. The film rarely goes beyond the surface but in fairness it knows that the surface is where we spend most of our time anyway. The reasons don’t matter. Only the possibilities that were destroyed.

One of the rare breed of films that didn’t provide Meryl Streep with an Oscar nomination (it did happen the following year for IRONWEED which reunited her with Nicholson) but the expert comic timing she displays combined with the inherent decency that she projects makes her the perfect match for the script’s point of view. Spending much of the film silently registering what people say without much of a response it becomes fascinating watching her reactions, the awareness on her face growing to the final awakening of how there’s nothing in this marriage left to fight for. Jack Nicholson was actually a last-minute replacement for Mandy Patinkin who was let go after a day of shooting (the first attempt at shooting THE TWO JAKES had just fallen apart so he was available and unlike, say, Dustin Hoffman no one would have mistaken him for Carl Bernstein) and the comic moments here are his best, particularly the intensity of his anger at the lack of work being done on the house. His own body language adds greatly to the performance as well, particularly when he shows up for the attempted reconciliation as if he’s a little boy who’s been found out but the rest of it is a little too vague, an unspoken annoyance covering up whatever else is going on. It’s a part that’s deliberately underwritten after the charm wears off so not much else comes through, he’s not playing Carl Bernstein but a sort of generic Washington “columnist” who apparently vacillates between politics and general observations of the world. We should all be lucky to have such a column. The supporting cast that backs them up is killer particularly Jeff Daniels as Rachel’s co-worker, clearly keeping quiet about a crush he seems to have on her and his gimme-a-break look during the wedding, sitting behind Maureen Stapleton with tears in her eyes, is one of my favorite things in the film. Steven Hill is also particularly effective, playing Rachel’s father as the epitome of facing loss and darkness in the world by simply moving forward (he gets maybe the best line too: “You want monogamy? Marry a swan.”). There’s also the likes of Stockard Channing, Richard Masur, Catherine O’Hara, Joanna Gleason, Mercedes Ruehl and Karen Akers as the much talked about Thelma Rice. The credited Natalie Stern as the Forman daughter Annie is actually the first screen appearance of Mamie Gummer, bringing an undeniable looseness to her scenes with the interest in her mother obviously genuine and not caring at all about whatever movie is taking place around them, the perfect reminder of the goodness that Mark Forman has chosen to ignore.

The bitter message of HEARTBURN may simply be a reminder to never get too happy. Because the pain isn’t worth it. In one scene they play a party game over dinner, describing themselves in just a few words as if to say that you only need to know the basics, just as only the gossip matters about a person. But when they’re close enough they do matter. In Richard Cohen’s book “She Made Me Laugh: My Friend Nora Ephron” he recalls that just after she died he received a phone call from Mike Nichols who had one question as he broke down: “What are we going to do now?” Sometimes you wonder that even when people haven’t died. If they’re gone, they’re gone. Even if there are reasons, there’s no point in saying them and those moments of lying in bed in the middle of the night watching an old horror film on TV eating spaghetti carbonara are nothing more than something only one of you remembers. Rachel keeps repeating how happy she is, only maybe with him it’s not about achieving happiness but about keeping that high going. Maybe, if you’re lucky, you’ll forget the best times or at the very least accept that they were nothing more than part of a dream you were living in. In the end, that might be the only way to stay alive.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)