Deciphering the Code of Cinema From the Center of Los Feliz by Peter Avellino

Sunday, January 28, 2018

Until People Stop Dying

In a lengthy profile on Robert Altman that ran in The New York Times on June 20, 1971, the director stated, “Nobody has ever made a good movie. Some day someone will make half a good one.” The following day I was born, emerging reluctantly into this world where no good movie had ever been made. A few days after that, Altman’s new film McCABE & MRS. MILLER opened in New York and he proved himself wrong. As far as I can tell, I was not taken to see it. Disappointments like that began early in life.

Regardless, every time I see McCABE & MRS. MILLER feels like the first time. I’m not sure if a Robert Altman film exists that doesn’t somehow transform as you get older and move further through the world but McCABE seems to do this more than the others. The world becomes richer, each shot becomes more layered, the characters become deeper as I cling to them, searching for them through all that hazy Vilmos Zsigmond photography and fuzzy audio that you might not hear all of at first. It took me 23 years until my actual first viewing, during a weeklong Warren Beatty series at the now closed Festival in Westwood leading up to the release of LOVE AFFAIR—this reminds me that LOVE AFFAIR, mostly forgotten these days, is roughly as old as McCABE was at the time which is all a little too depressing to contemplate. Already familiar then with some of Altman, I still wasn’t quite sure what to make of the film even as some of the imagery stayed with me long after, particularly from the ending, waiting for me to revisit and experience it again. Now all these years and however many viewings later, I still can’t get enough of McCABE & MRS. MILLER which seems to become something else every time through each new glimpse. However great it already was the film gets better, truer and more tragic as I try to fight through my own mist, forever becoming even more clueless about everything around me.

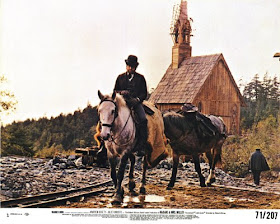

A mysterious gambler known as John McCabe (Warren Beatty) arrives in the tiny mining community of Presbyterian Church and soon asserts himself among the citizens, eventually acquiring several prostitutes that he brings to the town community begins to grow. After rejecting an offer of partnership from the local hotel owner Sheehan (René Auberjonois), McCabe is soon approached by Mrs. Constance Miller (Julie Christie), an experienced prostitute herself who has just arrived in town with an even better offer for partnership to bring in more, better girls and put together a high class establishment. The town continues to grow as their business booms and McCabe is soon approached by representatives of the powerful Harrison Shaughnessy mining company, looking to buy out their interests along with the mines to essentially take control of the town. But when McCabe acts a little too cavalier in the hopes of getting even more money out of them, Mrs. Miller warns him of what’s about to happen and McCabe soon realizes that his life may be in jeopardy with no chance to talk his way out of it.

Civilization evolves. Times change. People leave. And not only is there nothing we can do to stop this, it’s very likely the things we contribute to the world will be forgotten before anyone realizes it. The tiny northwest town of Presbyterian Church in McCABE & MRS. MILLER (screenplay by Altman and Brian McKay, based on the novel “McCabe” by Edmund Naughton) slightly resembles the MASH 4077th but it’s only partly about the community that emerges from the people who arrive there for whatever reason. Other Altman films keep the focus on the ensemble and how they relate to each other in whatever the distaff environment is but in this case the film is also about the title characters who for their own reasons remain separate, isolating themselves because that’s who they are. At the end of MASH everything cuts off when Hawkeye and Duke go home and it all just stops. In McCABE that loss is more complicated and much more painful, reaching for some kind of connection that never quite happens between the title characters.

It seeps into the look of the film courtesy DP Vilmos Zsigmond that was famously achieved through filters and a ‘flashing’ process during much of production which involved briefly exposing the negative to light in order to drain a certain amount of color out of the film. The riskiness in even attempting that has become part of the film’s legacy, the burnished look to give the impression it was somehow actually filmed way back then becoming at least as important as the star power of Warren Beatty which has led to various unwatchable video copies and problematic 35mm prints over the years--compared to the stunning Blu released by Criterion, the older Warner DVD really does look like mud and at an American Cinematheque screening a few years ago the theater announced they had to go through multiple prints before finding one good enough to show. The look of McCABE & MRS. MILLER makes more sense as the film goes on, as the town gets built up and we get used to it, we understand it even more and become attached to this place. It becomes part of the film and there’s nothing else quite like it.

It may not be the best Altman film (possibly NASHVILLE, but who’s to say) and I’m not sure I can call it my favorite (because, after all, THE LONG GOODBYE) but as much his directorial style was still forming at this early date it still feels like the most crystalized version we ever got of his approach to telling a story, to revealing who the people in front of his camera are and the world they inhabit. The Leonard Cohen songs used throughout as the score serve as the soul of it all, becoming as integral to the setting as the wind blowing through the air while transcending whatever they were first meant to be. Cohen’s “The Stranger Song” plays over the opening credits and serves as the only explanation of McCabe’s character that’s required and the haunting “Winter Lady” with those chimes heard off in the distance sounding like the entire summation of the regret of a life of experiences that was never fully allowed to happen. It all makes the film feel like a dream in a way, one where you’re never quite sure if you want to remain but you desperately hope you won’t wake up just yet. Altman himself called it an anti-western, a concept that I imagine meant more at the time when John Wayne was still making movies than it does now, but it almost plays as more of a non-western, merely a film set in the west of 1902 that trades off of certain familiar iconography while still becoming something else.

In its freeform way the film discards the clichés you expect from these archetypes in favor of who they really are when those personas are done away with whether the gunfighter that McCabe may or may not be, the whore (with a heart of gold), the comic relief, the hired killers, each of them never entirely what they’re supposed to be. In the end, Altman works with the genre on his own terms just as he always would. His version of the west starts off as one of the grimiest, muddiest environments ever seen onscreen with everyone gradually getting cleaned up as the town grows and the nature is taken away until a snowy climax where it overtakes that setting, becoming more bucolic as the violence gets more prevalent all in the middle of a nature that simply doesn’t care. Along with the music it’s also the silences that the movie fixes on where everything seems to stop, as if Altman realized while walking around those woods how absolutely quiet it could get and was determined to capture that allowing us to get a feel of what it’s like up there the rhythms are its own. Maybe more than any other Altman film this is one where he seems willing to expand its own pacing, to step outside of whatever is going on so this place and what it’s like to be there can be felt almost in ways that can’t be expressed.

Although not produced by Warren Beatty, making this one of the handful of post-BONNIE AND CLYDE titles he only acted in, it still feels of a piece with many of his iconic characters and the way they connect to each other as if in some sort of decades-long meta narrative. With McCabe muttering to himself while wearing his giant bearskin coat he seems to automatically assume the role of a leader in this hellhole that he helps turn into civilization, a star among bit players. It makes the film feel like it belongs equally to him as Altman, maybe more than any other top-billed star who worked with the director. Just as Beatty’s George Roundy in SHAMPOO would a few years later, John McCabe is able to talk a good game in a room and take charge at his own level even if he can never go beyond it due to his own foolhardiness. His ambition seems to stop at the belief that if he orders a round of drinks that alone will insure never ending loyalty and if he keeps talking they won’t realize how full of it he is. But McCabe doesn’t even know simple arithmetic, just as George Roundy had no idea about the specifics of getting a bank loan, and Mrs. Miller knows immediately how much he’s all talk and she wastes no time in calling him out on it. Possibly the only person he’ll listen to for more than a few seconds, she actually has an idea of how capitalism works and how to serve the market, while his first instinct when someone tries to reasonably negotiate with him is to repeat that damn “If a frog had wings joke…” for the hundredth time. The way he acts, the other people in the town are barely worth his attention so when he’s immediately assumed to be one ‘Pudgy’ McCabe who killed a man named Bill Roundtree in a card game through mysterious circumstances, he never confirms or denies those suspicions. Clearly, all that matters is they never know anything more about him, maybe even nothing more than he knows about himself.

If anything, he admits to himself that he’s got poetry but it’s only when he’s all along spitting out “Freezing my soul” to no one without even trying when thinking of her. And the more desperate he gets the more he tries to talk himself out of that desperation, as if all he’s got is what he can’t express like the poem Bonnie Parker read to Clyde Barrow or the poem that John Reed in Beatty’s REDS spent years obsessing over. Mrs. Miller keeps whatever her own poetry is to herself as if to emphasize the subtext of how much this film is also about Beatty and Christie as a couple, they go together. They’re the stars in this town but they’re a couple who are perfect but can never say the right thing to each other out of simple fear, simple stubbornness. Rene Auberjonois’ Sheehan tries to talk McCabe into being a partner before she shows up but he clearly doesn’t have the magnetism for him to care. Mrs. Miller does and is able to convince him through her own insistence but she’s still lost elsewhere in her own head, trapped in the opium daze that she doesn’t want to step out of and maybe that’s how it always will be for her. It’s never quite clear what their relationship is beyond at some point they start sleeping together and he’s paying her for it—it would be nice to think he’s the only one allowed such privilege but this is left ambiguous at best. It’s as if they want to be more than partners (‘comrades’ would have been the phrase in REDS), but it isn’t something they can ever say out loud. Of course, there’s only one ending any of these Beatty characters can come to, unless we’re talking about ISHTAR, and McCabe is sadly more foolish of any of them while still possessing the most determination in how he refuses to accept the inevitable. For a period of time he gets to drunkenly walk through the town like he owns it, which he sort of does, and what it becomes is largely due to his boastful nature anyway, just like the gangster he would later play who would one day get the idea to build up a town called Las Vegas in the middle of nowhere and that place would keep going after he disappeared from the world too.

It’s a wilderness that’s going to be destroyed just as the very idea of money and the lack of any real connection because of that is going to destroy the people, particularly these two people. Those that don’t care become part of the system. Those who try to somehow stay pure, whether it’s because they’re too stupid or not, pay the price. “He hasn’t got the brains,” one of the company men says about McCabe and we don’t want to admit how much we know he’s right. McCABE & MRS. MILLER may be about the impossibility of avoiding capitalism no matter how far you go or just avoiding what’s destined to happen to you, even out in the middle of nowhere, but it’s about the humanity hiding away from that world found there too, about how Mrs. Miller wolfs down that eggs & stew in an awe-inspiring way as McCabe, understandably mesmerized by her eating as well, sticks with the raw egg and whiskey he seems to entirely subsist on (eggs aside, the few mentions we get of what’s being served at Sheehan’s makes me glad I don’t have to try any of it) and outwardly she’s the most pragmatic of anyone in that town when it comes to how to survive but she eventually lets others see that humanity whether it’s McCabe or when she talks to Shelley Duvall’s widowed mail order bride even if she is only lost in her opium daze. It’s a town in the middle of nowhere that essentially turns into civilization, complete with segregated slums populated by the Chinese and a black barber who arrives with his wife and in the end have no problem with stepping away from the crowd while the church that shares the name of the town that is empty, unfinished, a shell like a façade on a backlot. In a west where the growing corporation does their business by sending out hired killers the faith is a shell anyway. In the end, there’s just the people who do their best not to notice.

Because this is Altman no scene feels like any other and there’s not a location in the town that feels used in the same way twice, each scene giving us this town from a different vantage point. It’s not always clear how much time the film spans, again just like a dream, and Altman’s habit of punctuating moments with zooms or other effects are at their very best here, always knowing just the right beat to end things on. He doesn’t go with the typical cinematic fantasy of old west prostitutes and everyone in the film, including Mrs. Miller referring to herself, calls them whores so I suppose we shouldn’t mince words but the men of the town never seem to have any complaints and every single one of them seems to know exactly who their character is even without an audible word of dialogue. When several of them join in on a chorus of “Asleep in Jesus” during a funeral scene and a pair of glances are exchanged between a pair of characters that almost becomes a fourth wall break about the inevitability of what's going to happen next, for a few moments this muddy masterpiece becomes one of the greatest works of art I’ve ever seen. It’s a film where all of the elements come together in a way that transcends merely thinking about genre even if it’s not always clear just how all those pieces are meant to fit.

There is the feel that you have to fight through that dialogue at times, the famous audio track that never becomes very clear but when William Devane gets one of the biggest chunks of dialogue of the entire film in his one scene as the lawyer (named “Clement Samuels” which presumably indicates how much he should be trusted) who McCabe goes to consult with it’s as if Altman is revealing all that dialogue for what it really is, just a lot of talk, so there was never any reason to listen to it. It’s the images and sounds that he’s interested in, the people who wander past while Warren Beatty is determined to take center stage that he’s interested in and he’s perfectly happy to let those images wash over so you can be devastated in the end. The one total innocent in the film, a cowboy played by Keith Carradine known only as “Cowboy”, has the most simple goal in the film so naturally he’s going to pay for it in the end, a reminder of the America that sprouted an extra head in summer 2015 and the one who confronts him even looks like a product of all that. Each time I see the film, when those outside forces enter and I know what it’s all leading to, my heart sinks a little. But that’s what the future is.

At one point it was called THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH WAGER then the rather dull JOHN McCABE before settling on the title it will always have, the one that makes the most sense. The title characters will only get together in a formal sense and unlike the myth presented in ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST, another film where The Woman with the Past stays indoors as the final shootout takes place, there’s not even a goodbye. McCabe, always looking to keep things on his own terms finally realizes that it’s not up to him anymore and the middle men who come to negotiate (it’s an Altman film so the ineffectual guy in a suit has to be Michael Murphy, even in the old west) eventually becoming the killers led by the imposing Hugh Millais emerging in a giant coat just like McCabe so he looks just as absurd but also just as ready to take over this town. As McCabe finally takes some action the snow endlessly falls and McCabe becomes one with the nature but the town, never even noticing this, moves on. They don’t need him anymore. And the haze that Mrs. Miller looks at the world through as she keeps to herself, too often fixed on her opium, overwhelms any other dreams she has when she tries to get through to McCabe or reading one of her books or simply listening to her music box. She can’t stop what she knows is going to happen and she’s unwilling to fight against the pain so she simply drifts off, Julie Christie when she’s last seen serving as the old west Starchild in the Altman-Zsigmond version of the end of 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (this has to be one of the best shots ever in a film, I'm sure of it). A person becomes part of where they are. They transform. Sometimes they get swallowed. Sometimes it’s inevitable.

The way Robert Altman films these two leads catches what they bring to the characters precisely and no one ever used them the way they are here. Much of Warren Beatty’s performance seems to depend on how many other people he’s in the frame with to relate to, always looking for the next game of chance, always looking for the next person to impress so when he’s left alone the character is at sea, which is when Beatty displays a vulnerability that he rarely ever has. And Julie Christie as Mrs. Miller seems to make the most sense when she’s left alone in the frame. She’s not trying to win anyone else over so it makes her even more tragic, fighting with herself over how much she’s actually caring about this guy with her cockney accent and how little good any of her hard work really is. Every single supporting actor is memorable as well, particularly René Auberjonois but there’s still John Schuck, Michael Murphy, Keith Carradine with the greatest “Aw, shucks” demeanor anyone ever had and, goddamn, the arc of Shelley Duvall who first arrives in the town as the mail order bride of Bert Remsen. As well as the icy pragmatism of Hugh Millais as the hired gun named Butler who arrives in town to “hunt bear”, maybe not quite seven feet tall as he’s described but wearing a coat that outmatches McCabe’s and not budging for a second in how much he can intimidate him just by sitting there. There’s not a face on the screen that doesn’t burrow into us, even if we never learn their name. Joan Tewksbury, later the screenwriter of NASHVILLE, is onscreen for mere seconds as a Harrison Shaughnessy employee and gets across the coldness of ever trying to deal with such an organization with no intent of ever helping anyone at all.

There are nights when I watch some of this film again, getting caught up in the staggering richness of the world it presents, and it’s a reminder that we have to drift through events in life by ourselves and much as we want to hold on to certain people it never seems to work. If I listen to Leonard Cohen singing “Sisters of Mercy” again for a few seconds I might think otherwise. That feeling passes quickly. But maybe it’ll come around again. As for Robert Altman films that were still to come, the ramshackle nature of the setting and almost comical extravagance of the costumes at times anticipates Altman’s POPEYE a decade later, a film my mother actually did take me to, and it plays like the more hopeful mirror image of McCABE & MRS. MILLER. But this isn’t the time to go back to the past. Right now, I just know that even as we remember those people they remain an illusion, little more than a memory that if we’re lucky we can hold in our hand. There are nights when I can accept that but the inevitability of it all still hurts. And it’s still true, from the day I was born all the way to now, all the way to infinity. Freezing my soul.

I love westerns and the songs of Leonard Cohen, I love the snow, and movies set in snow. But I don't love McCabe & Mrs. Miller. I'll grant it's a great film and one that looks, sounds and plays like no other. It's just that Altman's worldview is too bleak, his characters too lost and too doomed. It's such heavy sledding. And every time I hear Julie Christie speak her first overly-accented lines I wince as the rest of the cast's naturalistic delivery makes her's all the more jarring. There's darkness and wind, snow, widespread confusion, mistaken/assumed identities, people in and out of shadows, and a muffled and muddled overlapping murmuring throughout. What does any of it matter anyway? Or that Altman could so brilliantly and perversely tell the stories of characters better left forgotten? And yet. . . . . It remains as compelling as it is difficult for me and always worth the effort.

ReplyDeleteThanks for posting this. It set me to recalling another snow-bound Altman film, released about 5 years later, with Paul Newman starring in "Quintet" as a survivor in a post-apocalyptic ice-aged wasteland. I saw it when it was released and it cratered at the box office and was so thoroughly shelved that it might as well have been buried beneath all that ice. After something like 4 decades, maybe its time for it also to be exhumed and blue-rayed?

Terrific piece. If I may add one thought: it's almost a shame Altman didn't direct more action. The shootouts in M&MM stop my heart every time I watch them.

ReplyDeleteEsoth Max--

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you liked the piece, even if I guess I'm looking forward to my next viewing a little more. These days I'm feeling a little drawn to that bleak worldview. I guess it feels worth the effort, as you put it, the more I've kept going with the film over the years. As for Quintet, I've perversely thought about trying to write something but haven't been able to bring myself to do it. For one thing, it would mean I'd have to see it again. I guess I sort of admire it in some sort of anti-cinema way but trying to come up with something to say might hurt my head too much.

YZF--

Very glad you liked it, thank you! Those final 20 minutes are quite remarkable in how Altman lays out the action. We think about him so much in covering scenes from one angle with a zoom lens that we forget just how good he was at matters of geography and visually following what was going on in any given scene.