Deciphering the Code of Cinema From the Center of Los Feliz by Peter Avellino

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Good Against The Living

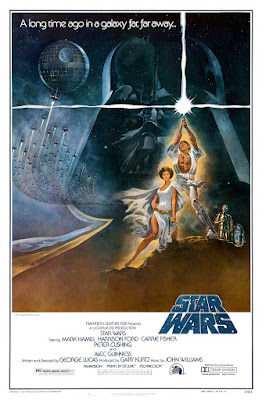

At the end of AMERICAN GRAFFITI, Richard Dreyfuss as George Lucas avatar Curt Henderson looks down from the plane taking him away from childhood in Modesto where below he sees the elusive white T-Bird driven by Suzanne Somers one more time as if to say farewell to him, to his youth. He’ll never really find her but that’s ok. When it comes to destiny, you have to keep moving. You could ask what Luke Skywalker would have done if those droids had never shown up to take him away from his uncle’s farm on Tatooine but he would have figured out a way to leave eventually because that was his destiny. STAR WARS opened and exploded during the summer of ’77 when a few other films dealt with destiny in their own ways. In William Friedkin’s SORCERER, Roy Scheider travels to the ends of the earth to avoid punishment for his crimes but, as things turn out, he never travels far enough. Which in its way is just as inevitable as the ending of Martin Scorsese’s NEW YORK, NEW YORK which actually opened the same week as the Friedkin film in June of that year, presenting the breakup of Liza Minnelli and Robert De Niro as inevitable as their varying degrees of success. Each film plays as an example of what the directors saw as the possibilities of their place in the world and it’s all about whether you can still exist once you’re there. AMERICAN GRAFFITI is about the past, about leaving. STAR WARS, a futuristic look at what it presents as the past, is about the arrival.

The thing about George Lucas’ 1977 film STAR WARS is that it’s presumably meant for the kid in all of us, the kid still looking to discover what their own future is going to be. Of course, all this presupposes we actually want to let the kid out in the first place as long as we’re not too hardened by where we’ve ended up in life but it makes sense that a film like this is an immature one, about people who haven’t yet encountered all the hardships that come with age and failure, from the destruction of the planet Alderaan which barely even gets commented on fleetingly to the groundbreaking special effects which have a tinge of 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY but after an opening shot where we take in the enormity of the Star Destroyer chasing the tiny ship belonging to the good guys it never quite pauses for the same kind of awe, always going for the sensation over the majesty. It’s not that there’s anything wrong with this approach and STAR WARS never wants to be a deep film anyway, never more complicated than all the potential for greatness that lies before you when starting out, a feeling you sometimes fight to hold onto and don’t always succeed.

The bare bones of the plot of STAR WARS don’t need to be gone over again, they barely matter anyway. It is, after all, a quest that seems connected to any other fantasy tale half-remembered from when you were a kid found in the story of Luke Skywalker, boy farmer on the desert planet of Tatooine in a faraway galaxy, who makes a discovery which takes him away to a magical place where he learns something about himself that places him on his path in life. It’s myth, that’s what it really is and never more complicated than that. The Death Star plans hidden away for him to find are the McGuffin, the mysterious power that is the Force with its light and dark sides is the morality, the plot is the excuse.

Of course, the plot does matter in the way the story is told and at times it matters brilliantly in how the elements are juggled with dialogue that breathlessly reveals all that exposition as instantly iconic. But there’s still the question of how much plot ever really matters anyway because more than its Wizard of Oz/Flash Gordon/Lord of the Rings/whatever else mashup of mythology so much of the film is about the emotional effect that comes from what the sensation delivers. STAR WARS in its own way is a combination of all films and what that larger than life mythos coming from any of them can mean to us deep down, with characters that are true archetypes we know everything about the second they appear onscreen, whether good and bad. Everything about them is clear and all we need to know is what they’re going to do next.

Serving as our entryway into the film, the droids R2-D2 and C-3PO only seem like they’re going to be the leads in the first fifteen minutes which in itself is one of the bravest things about the film, avoiding a real human connection for as long as possible but making them endearing as Laurel & Hardy-styled comic relief or maybe fools right out of Kurosawa or Peckinpah, commenting on the action and occasionally moving it forward, even if by accident, and once the humans take center stage everything about the world already makes sense. That humanity is found in the trio of Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher) and they’re the ones who really bring the film to life, each one instantly vivid in their characterizations. By the time we meet Luke we’re as acclimated to this world as he is, relating to his whining and staring at the binary sunset as he yearns to get away. He’s the one we lock into whether we want to admit it or not and his frustrations make sense just as much of Princess Leia’s defiance. The glimpses of her in actual distress are so fleeting and it’s as if much of her characterization can be found in the John Williams theme for her, an idealized vision of her set to music that she spends much of her screentime fighting against, looking to take control instead when her rescuers have no idea what to do. Han Solo, meanwhile, always seem to turn up in the film a little later than I expect, with loyal sidekick Chewbacca next to him, but he emerges so fully that he barely needs to be introduced anyway, a man who answers to no one except for the alien gangsters he’s being chased by, everything said about him is clear when confronted by bounty hunter Greedo over an old debt as if his AMERICAN GRAFITTI character Bob Falfa was reborn in this other galaxy and is suddenly given a reason to believe in something more than all the strange stuff he’s already seen. The older figures around them ground that feeling, given the task of bringing gravity to dialogue which hints at greater events around them particularly with everything implied in the very presence of Alec Guinness as Obi-Wan Kenobi, the former Jedi Knight who in his total calm seems to think back on past events with every glance and utterance. It’s his belief in the Force that provides the film with a center, someone who has seen more than he’ll ever talk about, instead carefully passing along his wisdom with such a calm that we instantly believe his reasons for not believing in luck and that there really is a larger world out there if we’ll only choose to look for it.

On a cinematic level it's meant to be an update of old serials using the filmmaking approach of the New Hollywood and every technological advancement imaginable which thinking back to the time it came out feels revolutionary, taking what was likely thought of as junk back in those days and turning it into something which is as good as it always felt like it could be in the covers of old science fiction novels, the all-powerful space station the Death Star serving as the dark fortress of it all with the image of the mysterious Darth Vader, the figure of all-purpose evil given a mysterious backstory and connection to the Force that Kenobi must confront. The strength of every moment is a part of the filmmaking prowess George Lucas brings to it and just as Steven Spielberg is always moving his camera in something like RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, Lucas as director is more about the sole purpose of working out the puzzle to put the shots together aided by the sharpness of the framing thanks to Gilbert Taylor, also cinematographer of DR. STRANGELOVE, A HARD DAY’S NIGHT and REPULSION, which crystalizes the way everything should look. Along with that look and the tempo taken from those acting styles it’s how every one of those pieces fits in with the pacing thanks to the editing by Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas and Richard Chew that makes the shots add up, not always about the individual moment but the way those frames go together, what in the days of Eisenstein would have been called the ‘montage cell’ in how every single shot is not just another part of a sequence but really just one piece of the overall body with a specific purpose. This approach is strongly revealed in some of the best set pieces particularly in the unrelenting kineticism of the TIE Fighters pursuing the Millennium Falcon after the escape from the Death Star but even simple dialogue scenes are given an extra kick by the movement found in the edits or those wipes during scene transitions meant to recall an old fashioned flavor of pulp combined with the naturalistic feel of what was still then the 70s approach, apparent in touches like the relatively sparse use of music at times which lets us pick out what really matters for ourselves.

The story is of course already in progress when the film begins with even what sounds like a key battle serving as nothing more than background in the opening crawl, just like C-3PO is all beat up and dirty for reasons we never learn. The characters aren’t impressed by everything around them so the film doesn’t need to be either and the conversational nature of the dialogue, revealing fantastic things in a matter of fact way, always gets to the point. There may be so much about this universe that isn’t found within the widescreen frame and so many questions about it all even though it’s probably futile to expect total logic from this but so much of what’s there allows us to fill in the blanks. The script, credited to Lucas, slices what we need to know down to its essentials while never getting too lost in all the fantasy jargon even with his fetish for lots of numbers referenced in dialogue whether the Stormtrooper named TK-421 who won’t respond or the new BT-16, whatever it is, that’s apparently quite the thing to see. The script was also reportedly worked on by AMERICAN GRAFFITI co-writers Willard Hyuck and Gloria Katz so the Luke-Leia-Han triangle plays a little as a revisit of the main relationships in their screenplay for the 1975 Stanley Donen film LUCKY LADY, another attempt at an old time pastiche which did more than just imply what was going on between the threesome of stars Liza Minnelli, Gene Hackman and Burt Reynolds, it literally put all of them into bed together. STAR WARS of course keeps the sex out of things and sticks to the enjoyable banter, a sense of carefree innocence in the air during the final moments as if these three will be perfect together the way they are.

As director, Lucas always operates with an eye towards the details whether all those ever-present Stormtroopers, the eternal mystery of the lookalike droid behind C3PO in the opening moments or even how the revolutionary Ben Burtt sound work makes R2-D2 a fully fleshed out character. But even when on the surface the action should be generic like the endless running around the Death Star, the scenes always have an extra kick whether laughs at just the right moment, how much the actors play the tone just right or just the unrelenting sense movement that never lets the tempo slow down for too long. Even the mayhem is placed correctly up against the eerie quiet of other moments, particularly when focusing on Obi-Wan Kenobi’s journey around the massive space station in the way he takes care of the tractor beam or the simple calm of finding Vader standing before him, waiting for the inevitable. The design of the Death Star and the coldness of the corridors that seem to go on forever add to that feel while each spaceship design has just the right amount of character to make us want to see what each of them can do.

This version of outer space is a different yet recognizable universe, with elements like the funhouse quality of all the creatures in the cantina scene, full of touches that add to the old movie tropes whether from old westerns or CASABLANCA and up against all that the special effects are groundbreaking, yes, but the way the rhythm of the film itself responds to it so to create this universe means there’s not a wasted frame, nothing is missing. It’s not that the film ever has a huge amount on his mind—buried under the intellectualism of the Eisensteinian cutting style and not so hidden left wing slant to the rebels in their fight against the evil Empire it’s about the emotion of the moment, a reminder that sometimes what the best films can do to give us this feeling, itself a kind of propaganda to inform us not through speech but the pure cinematic combination of sound and image. Even down to the final bars of the closing credits where the spectacular John Williams score, itself a tribute to both classical music and all sorts of Hollywood adventure films of the past seems to quote a passage from Alfred Newman’s “Street Scene” overture at the start of HOW TO MARRY A MILLIONAIRE or the use of the Fox CinemaScope extension in its fanfare at the beginning as a way to definitively announce that this is a larger than life Movie just like they used to make, at least in our dreams.

In the end, it feels like STAR WARS is about making the decision to go off and live the life which helps you comes to terms with that destiny, letting go of the past that terrifies you to figure out who you really are. In a way, Luke’s decision to turn off his targeting computer before his final shot at the Death Star’s exhaust port is an odd case of the film rejecting the technology it wouldn’t exist without yet it’s still the perfect conclusion to his arc here, to figure out the world by using whatever lies within yourself to make that leap forward. And even with all this technology to produce the visual effects the film plays as effortless as it should and the ever-present charm comes out of that feeling. That’s the masterful exhilaration of the final Death Star battle which is all about that pacing and how the unrelenting rhythm gets into our heads, the excitement that grows with every single new shot which allows it to be analyzed endlessly right down to the power of that cut from Peter Cushing’s Tarkin to the very last second of the Death Star right before the explosion. It’s a feeling we never get rid of that matters more than plot or where those revelations are going to lead ever could, always moving forward towards destiny.

The lead performances match the tone perfectly in all their excitement with the uncomplicated boyishness of Mark Hamill, the adroit fearlessness of Harrison Ford, the Hawksian determination of Carrie Fisher who also brings a touch of regality to the dialogue she plays with Peter Cushing, rolling his r’s like nobody’s business and having a glorious time in his ice-cold ferocity. Alec Guinness is particularly enjoyable to watch as he bounces off Hamill and Ford, his bemused nature bringing all the weight in the world to even the smallest of moments, even if it never quite brings out the desert eccentric ‘Ben’ Kenobi allegedly is. But this really doesn’t matter, not when his very presence adds so much and his final smile to Luke as he goes off to deal with the tractor beam provides all the human connection the film needs. Even the small roles pop like Richard LeParmentier in his run in with Vader as the cocky Admiral Motti, the weathered nature of Phil Brown and Shelagh Fraser as Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru but also particularly a few of the rebels during the climax who have stayed in our heads all these years and seem to develop full characterizations while doing nothing but spout battle jargon, each one achieving a certain kind of immortality in their X-wing fighters.

STAR WARS famously opened at Grauman’s Chinese on May 25, 1977, the day after a celebration at the theater to commemorate its fiftieth anniversary which included a special showing of KING OF KINGS. The symbolism of this is tough to overstate, almost dividing much of film history itself into what came before STAR WARS and what has followed after. And who knows what filmmaking is even going to be once we pass the fifty year mark on this one. Of course, just as STAR WARS, the film called simply STAR WARS, doesn’t really have a beginning it also doesn’t really end, merely concluding with this victory over the Evil Galactic Empire. Sure there was more to come but it’s as if by this point George Lucas really has embraced his destiny with this achievement, the blonde in the white T-Bird far in the past, and after that nothing else needs to be said. In the 70s up until STAR WARS was released it seemed like pretty much every ending was downbeat, except for maybe JAWS, ROCKY and FREEBIE AND THE BEAN. But after this and the rapture of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND soon after those endings no longer seemed of the time, as if it was suddenly a film’s job to remind us that everything was going to be ok and nothing more. Not that it was the fault of these individual films, mind you, but it did happen. And even now the film that goes by the name STAR WARS plays as a reminder of how we always need to move forward, no matter how afraid we are of what might happen. Although we should still remember that happy endings are always happy until they’re not. Because even destiny doesn’t necessarily lead us where we think it will. No matter how exhilarating the trip is.

No comments:

Post a Comment