Deciphering the Code of Cinema From the Center of Los Feliz by Peter Avellino

Tuesday, December 31, 2019

The Rest Is Waiting

It can be near impossible to avoid thinking of the past, especially at the end of the year. Remembering what you did, how you screwed up, or if you did anything at all. And sometimes you think even further back, as far back as a decade, wondering what your world used to be and how things changed, going over the things you did wrong and what you could have done instead. In our minds we hope for the best, we have to, but it can be difficult to face the truth as we wonder how much time we really have. Too much becomes our own fault if we’re willing to admit it. So at the end of the year, at the end of the decade, maybe all we have left is the chance to just wait for the next one, the next chance to make everything all right. That is, if there really is a chance.

If Bob Fosse is ever in danger of being forgotten that was likely delayed in 2019 with the airing of the FX miniseries FOSSE/VERDON which was enjoyable but never very substantial in spite of inspired moments from some of the performances. Drawing conclusions based on what seemed to be its own thematic goals more than anything having to do with history, watching it was like eating halfway decent Chinese food; enjoyable to munch down on but it left me feeling empty in the end. Some of the stylistic approach was clearly inspired by Bob Fosse’s own films, because how could it not be? And when I say ‘stylistic approach’ I’m basically saying it was hard to watch it at times and not think, isn’t this just ALL THAT JAZZ? And it didn’t even spend much time on ALL THAT JAZZ. Regardless, ALL THAT JAZZ turned 40 this year and it wasn’t Fosse’s last film but feels like it was meant to be, possibly serving as the final statement of a creative life and everything that it meant. ALL THAT JAZZ is exhilarating and addictive like few other films I can think of, one that draws me back to examine it, to wrestle with it, to try to deal with it, wishing that what happens could go in another direction even as you know the inevitable. Kind of like a recent decade I can think of. But unlike that decade, as I go back to this film I ultimately embrace it. It means too much to me, it speaks too much to me. It’s about as close to a perfect film as I can think of but it’s also better than that, not a pristine jewel but a complicated piece of work that’s still messy enough to allow for exploration of its parts and what it all means while trapped in the parade of our own lives. Maybe while trying to figure it out I find myself in there, but I suppose we all do.

Legendary choreographer Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider) is beginning rehearsals on the new Broadway show that he’s directing while simultaneously attempting to finish editing his latest film. As his days ping-pong back and forth among the various projects with the women in his life all a part of it, including ex-wife Audrey (Leland Palmer), off-and-on girlfriend Katie (Ann Reinking) and daughter Michelle (Erzsebet Foldi) while in his head we see Joe with the only women he can be totally truthful with, a spectre of death named Angelique (Jessica Lange) who of course knows all his secrets. But when he’s rushed to the hospital with chest pains in the middle of working on the show, Joe’s total denial of his condition soon begins to catch up to him and he can’t fight where all this is going for very much longer.

It’s showtime, folks, as Joe Gideon says to the mirror every morning with his Vivaldi tape playing as he puts on his face on for the world, ready to start the performance all over again, even if he knows he can’t hold this face forever. Written by Robert Alan Aurthur and Fosse, ALL THAT JAZZ is an extraordinary film but it’s the kind which feels like it was never meant to be anything but an extraordinary film. What would be the point if it wasn’t? A musical unlike any other, an examination of the Broadway world and a man at the center of it with an energy to it all that puts us right in there. So much of what we’d ever need to know about Joe Gideon is his morning ritual complete with cigarette hanging from his mouth in the shower, but it’s the opening audition montage set to “On Broadway” that tosses us in without any orientation as if we’re one of those dancers looking to be validated by this legend but it gets us to understand the world instantly. The desperation of all those hopefuls isn’t his problem and to him the work which leads to all that brilliance is all there is, searching for his own inspiration as he choreographs his dancers, no qualms about fucking some of them who he may or may not decide to cast before torturing them to do better. Even the ones he’s not fucking get some of that treatment anyway.

The cutting style is as insistent as CABARET but this isn’t an extension of Fosse’s earlier films as much as a culmination of them but of course it’s really a culmination of his whole life anyway. And even more than those other films ALL THAT JAZZ is unrelenting in its pacing with each new shot adding to the intensity of the neverending delirium. To be on the wire is life, says Joe, the rest is waiting. It’s a justification for what he does, the pain he causes, the sound of coughing heard right from the start which serves as a tell of where this is all going to go. Angelique points out how theatrical the phrasing is while also getting Joe to admit that he didn’t come up with it. Everything about his life needs to be theatrical and even if someone in this day and age doesn’t know Bob Fosse, it’s impossible not to get a sense of a life that never slows down, that never waits. And Joe Gideon clearly never had any interest in waiting.

ALL THAT JAZZ is no doubt supposed to be too much, gloriously so, with an approach that goes beyond what you'd expect from any normal film with truly phenomenal musical numbers that go on and on to the point that you realize they have to be that long to mean as much as they do. Even the stylistic extremes it goes to during unexpected moments add to this feel whether the hospital delirium of the second half or the way all sound drops away during the script reading when Joe mentally checks out. But it’s how Fosse seems to find a way to shoot every moment with such life and vitality in the first place, the spectacular Airotica number for the backers of his new musical NY/LA featuring the truly awesome Sandahl Bergman coming out of seemingly nowhere and the power it gives off even in that tiny rehearsal space makes us dream not only of the fully produced version but offers an unexpected intensity which allows us to fully believe in his talent that's been talked up so much, even if it does come out of his own insecurity and desperation. That’s what the film does, especially in the first hour when it’s the creativity being focused on and it plays like a drug.

Over multiple viewings through the years I would gravitate towards that first hour and its unrelenting exhilaration, then feeling always a little let down when Joe entered the hospital for the second half where it would feel like the momentum halted. But seeing the film in 35mm at a New Beverly screening a few years ago (paired with LENNY) it all made sense—this is one of those nights at that theater which has stayed with me, a packed house (an audience that included Robert Forster, who we lost this year) that gave the night an undeniable energy felt from the unrelenting power of the second half that as it went on became emotionally overwhelming by a certain point, taking this film I’d already seen before multiple times and transforming it via that cinematic experience into something that I didn’t want to let go of, just as Joe Gideon doesn’t want to let go, as if the film ever let you off the hook that energy would dissipate.

Just as Bob Fosse was and in some ways still is, Joe Gideon is a god in this world with the way all his dancers look at him, whether he’s already fucked them or not, always looking for the answers they know his genius will provide, no matter how much he anguishes and the seduction of one of them set to Nilsson’s “Perfect Day” playing catches the perfect mood for the seduction. With Joe looking out from the cutting room of his big budget film at a strip club across the street to remind him that the two aren’t so far apart, the cynical laughs come from the inside sleaze of this world and the money men without a shred of art in their bones, so it’s all how much his life when he’s not around to be an artist comes down to dollars and cents. At times in watching this film I’ve wanted a little more of the world around these people, connected to all those young girls limbering up all over the place and the 1979 New York out there on the streets but that’s never where Joe Gideon is, he’s inside in that showbiz world where it feels like you’re going to live forever, like the 24 year old who finally gets “a house in Beverly Hills” that his ex-wife Audrey is so determined to play. It’s an entire world based on putting off death, no matter what the subject of the musical is (I’d still like to actually see NY/LA, whatever it might be) but it's also about putting off anything resembling an actual commitment that would take you away from it all just as Ann Reinking, more or less playing herself as girlfriend Katie, knows which buttons to push as she desperately tries to get him to give her a reason to stay.

The film is overwhelming but it has to be and it’s the only way for it to make sense, while Joe Gideon stands in the center of it, already aware of what everyone wants from him. Gideon’s latest film that he’s editing is so obviously meant to be LENNY it doesn’t even try to hide that, with the film’s comic played by Cliff Gorman, who won a Tony for playing Lenny Bruce on Broadway only to have Dustin Hoffman take the role in the film version. The glimpse at the cutting process shows him listing off the five stages of death as part of his stand-up routine, patter that gets repeated a few too many times and it’s maybe the one thing in the film that strains my patience over multiple viewings. But it’s not like subtlety is ever really the goal, either in this world or in this film and even the repetition feels intentional, a reminder of what Joe is working on running in his head over and over so when his film gets trashed by a critic for giving free reign to the star, after all the time he’s spent obsessing over every tiny change in the cutting room, it’s a clear sign that the people who aren’t there for the creation don’t know. Joe’s talent, if not his brilliance, is never in question, but it’s clear none of that means anything if everything else is ignored. Maybe in trying to analyze ALL THAT JAZZ all anyone can do is simply not become that snarky critic and just try to understand what the film means for them deep down in a way they’ll someday have to admit to themselves.

It’s the whole death thing that matters in this freeform dive through Joe Gideon’s mind, going perfectly with the forced gallows humor that he can’t keep up forever. That attraction to it he’s always had only adds to the delirium of his interior dialogue with Angelique and the whole unresolved Fellini quality of these scenes, always feeling like there’s something outside of the frame in his subconscious. It’s like the film is a non-stop war between the danger of his lifestyle and how much living in this world gives us the rush of creativity, whether the eagerness of the dancers in the rehearsal scenes or with Katie and Michelle’s private performance of “Everything Old Is New Again” just for Joe, serving as the feeling of what this music does, what all this does, if only it could always be this joyous, keeping the cynicism at bay for a few minutes. Through all this is a game of which past Fosse project is being referenced at any given time, not to mention whatever he’s pulling from his own life and all of this detail means every new shot pierces your soul, shepherded by the editing mastery of Alan Heim (who appears onscreen as the editor of THE STAND-UP, adding one more mirror to things) in connecting the richness of those images photographed by Giuseppe Rotunno together. It all remains completely alive right up until the very last shot, which as anyone who’s seen the film knows is the way it has to be.

However critical (or self-critical) the film is about him, it’s done in a way that is deliberately self-regarding as if Bob Fosse himself in the guise of Joe Gideon saying, I’ll hate me enough for both of us so please love me. Which is still a justification in the midst of all that self-loathing but it still feels more honest than the FOSSE/VERDON approach of simply trying to poke holes in the myth. The unrelenting and extraordinary “Bye Bye Life” sequence which serves as the finale puts the lie to the concept of people criticize a scene like this for simply being indulgent because there is no film otherwise, there’s no way it would come anywhere near this power if it wasn’t. And without it we wouldn’t feel the tragedy of what’s being lost and grieved in the shot of Joe’s daughter embracing him one last time. There's no point in saying 'if only he could have known' because of course he did. It just didn’t do any good. He is who he is. We’re all who we are as we get closer to the end, facing a little piece of truth at the end of each year, like no business I know.

Roy Scheider, Oscar-nominated for this performance, is absolutely remarkable and totally transformed, without an ounce of his more familiar screen persona and light years beyond anything else he ever did, making me wish we’d gotten more of this side of the actor in the following years but how many films like this are ever made? Even if the film has to shoot around how he’s not really a dancer, Scheider’s very physicality in every movement sells it and he perfectly finds the balance of where his brilliance comes from, how he can command a room even while that self-loathing is never far behind. Maybe because in spite of everything we still see ourselves in there. Playing Joe’s ex-wife, the remarkable Leland Palmer (who I guess we mostly know for serving as the namesake for a certain famous fictional character) finds just the right balance between her bitterness and being unable to hide her unending love for him, always finding something unexpected in the tiny moments including the very last thing she does in the film. As his current girlfriend, Ann Reinking builds up to the yearning she feels for him until it can only be contained in giant close-up, desperate for a shred of his love, whatever he really feels. Erzsebet Foldi as Joe’s daughter is almost too believable in what looks to be her only screen appearance, displaying such directness when acting with Scheider and such joy in her musical numbers that provides more raw emotion than anything else in the film while Jessica Lange, somewhere between KING KONG and TOOTSIE, tantalizes as the vision of death outside the main world of the film but always ready to challenge Joe on his legend, knowing what has to come eventually. Every performance, however small, fits perfectly including Deborah Geffner’s dancer looking to be a movie star and willing to be seduced by Joe, the desperation of Anthony Holland’s songwriter to keep the show going, Ben Vereen’s oozing insincerity as “O’Connor Flood” always making introductions on his variety show and the nasty, fragile ego of John Lithgow as rival director Lucas Sergeant.

Like it or not, the end of the year always feels like waiting anyway. You’re done with the holidays, itching to get back to whatever it is you do and just want to see the damn ball drop already. But The End is still something we think about since it can mean a lot of things. Even Bob Fosse made it another eight years after this so there was no way for him to know everything about it, not even after making this film. For a film about The End, ALL THAT JAZZ is still alive like few other films I know. Maybe because in its way the film is saying don’t be afraid of all that, just try to do a few things better while you’re here. Don’t fuck up. That’s the sort of lesson worth taking from what might be one of the best films ever made. So, as the New Year approaches, it’s back to waiting as I get ready to begin again. Sometimes we don’t have a choice.

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Good Against The Living

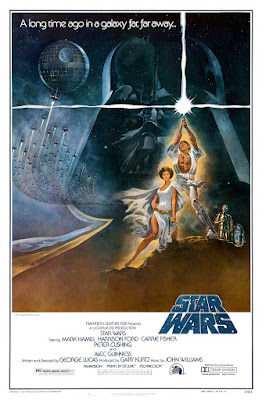

At the end of AMERICAN GRAFFITI, Richard Dreyfuss as George Lucas avatar Curt Henderson looks down from the plane taking him away from childhood in Modesto where below he sees the elusive white T-Bird driven by Suzanne Somers one more time as if to say farewell to him, to his youth. He’ll never really find her but that’s ok. When it comes to destiny, you have to keep moving. You could ask what Luke Skywalker would have done if those droids had never shown up to take him away from his uncle’s farm on Tatooine but he would have figured out a way to leave eventually because that was his destiny. STAR WARS opened and exploded during the summer of ’77 when a few other films dealt with destiny in their own ways. In William Friedkin’s SORCERER, Roy Scheider travels to the ends of the earth to avoid punishment for his crimes but, as things turn out, he never travels far enough. Which in its way is just as inevitable as the ending of Martin Scorsese’s NEW YORK, NEW YORK which actually opened the same week as the Friedkin film in June of that year, presenting the breakup of Liza Minnelli and Robert De Niro as inevitable as their varying degrees of success. Each film plays as an example of what the directors saw as the possibilities of their place in the world and it’s all about whether you can still exist once you’re there. AMERICAN GRAFFITI is about the past, about leaving. STAR WARS, a futuristic look at what it presents as the past, is about the arrival.

The thing about George Lucas’ 1977 film STAR WARS is that it’s presumably meant for the kid in all of us, the kid still looking to discover what their own future is going to be. Of course, all this presupposes we actually want to let the kid out in the first place as long as we’re not too hardened by where we’ve ended up in life but it makes sense that a film like this is an immature one, about people who haven’t yet encountered all the hardships that come with age and failure, from the destruction of the planet Alderaan which barely even gets commented on fleetingly to the groundbreaking special effects which have a tinge of 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY but after an opening shot where we take in the enormity of the Star Destroyer chasing the tiny ship belonging to the good guys it never quite pauses for the same kind of awe, always going for the sensation over the majesty. It’s not that there’s anything wrong with this approach and STAR WARS never wants to be a deep film anyway, never more complicated than all the potential for greatness that lies before you when starting out, a feeling you sometimes fight to hold onto and don’t always succeed.

The bare bones of the plot of STAR WARS don’t need to be gone over again, they barely matter anyway. It is, after all, a quest that seems connected to any other fantasy tale half-remembered from when you were a kid found in the story of Luke Skywalker, boy farmer on the desert planet of Tatooine in a faraway galaxy, who makes a discovery which takes him away to a magical place where he learns something about himself that places him on his path in life. It’s myth, that’s what it really is and never more complicated than that. The Death Star plans hidden away for him to find are the McGuffin, the mysterious power that is the Force with its light and dark sides is the morality, the plot is the excuse.

Of course, the plot does matter in the way the story is told and at times it matters brilliantly in how the elements are juggled with dialogue that breathlessly reveals all that exposition as instantly iconic. But there’s still the question of how much plot ever really matters anyway because more than its Wizard of Oz/Flash Gordon/Lord of the Rings/whatever else mashup of mythology so much of the film is about the emotional effect that comes from what the sensation delivers. STAR WARS in its own way is a combination of all films and what that larger than life mythos coming from any of them can mean to us deep down, with characters that are true archetypes we know everything about the second they appear onscreen, whether good and bad. Everything about them is clear and all we need to know is what they’re going to do next.

Serving as our entryway into the film, the droids R2-D2 and C-3PO only seem like they’re going to be the leads in the first fifteen minutes which in itself is one of the bravest things about the film, avoiding a real human connection for as long as possible but making them endearing as Laurel & Hardy-styled comic relief or maybe fools right out of Kurosawa or Peckinpah, commenting on the action and occasionally moving it forward, even if by accident, and once the humans take center stage everything about the world already makes sense. That humanity is found in the trio of Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), Han Solo (Harrison Ford) and Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher) and they’re the ones who really bring the film to life, each one instantly vivid in their characterizations. By the time we meet Luke we’re as acclimated to this world as he is, relating to his whining and staring at the binary sunset as he yearns to get away. He’s the one we lock into whether we want to admit it or not and his frustrations make sense just as much of Princess Leia’s defiance. The glimpses of her in actual distress are so fleeting and it’s as if much of her characterization can be found in the John Williams theme for her, an idealized vision of her set to music that she spends much of her screentime fighting against, looking to take control instead when her rescuers have no idea what to do. Han Solo, meanwhile, always seem to turn up in the film a little later than I expect, with loyal sidekick Chewbacca next to him, but he emerges so fully that he barely needs to be introduced anyway, a man who answers to no one except for the alien gangsters he’s being chased by, everything said about him is clear when confronted by bounty hunter Greedo over an old debt as if his AMERICAN GRAFITTI character Bob Falfa was reborn in this other galaxy and is suddenly given a reason to believe in something more than all the strange stuff he’s already seen. The older figures around them ground that feeling, given the task of bringing gravity to dialogue which hints at greater events around them particularly with everything implied in the very presence of Alec Guinness as Obi-Wan Kenobi, the former Jedi Knight who in his total calm seems to think back on past events with every glance and utterance. It’s his belief in the Force that provides the film with a center, someone who has seen more than he’ll ever talk about, instead carefully passing along his wisdom with such a calm that we instantly believe his reasons for not believing in luck and that there really is a larger world out there if we’ll only choose to look for it.

On a cinematic level it's meant to be an update of old serials using the filmmaking approach of the New Hollywood and every technological advancement imaginable which thinking back to the time it came out feels revolutionary, taking what was likely thought of as junk back in those days and turning it into something which is as good as it always felt like it could be in the covers of old science fiction novels, the all-powerful space station the Death Star serving as the dark fortress of it all with the image of the mysterious Darth Vader, the figure of all-purpose evil given a mysterious backstory and connection to the Force that Kenobi must confront. The strength of every moment is a part of the filmmaking prowess George Lucas brings to it and just as Steven Spielberg is always moving his camera in something like RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, Lucas as director is more about the sole purpose of working out the puzzle to put the shots together aided by the sharpness of the framing thanks to Gilbert Taylor, also cinematographer of DR. STRANGELOVE, A HARD DAY’S NIGHT and REPULSION, which crystalizes the way everything should look. Along with that look and the tempo taken from those acting styles it’s how every one of those pieces fits in with the pacing thanks to the editing by Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas and Richard Chew that makes the shots add up, not always about the individual moment but the way those frames go together, what in the days of Eisenstein would have been called the ‘montage cell’ in how every single shot is not just another part of a sequence but really just one piece of the overall body with a specific purpose. This approach is strongly revealed in some of the best set pieces particularly in the unrelenting kineticism of the TIE Fighters pursuing the Millennium Falcon after the escape from the Death Star but even simple dialogue scenes are given an extra kick by the movement found in the edits or those wipes during scene transitions meant to recall an old fashioned flavor of pulp combined with the naturalistic feel of what was still then the 70s approach, apparent in touches like the relatively sparse use of music at times which lets us pick out what really matters for ourselves.

The story is of course already in progress when the film begins with even what sounds like a key battle serving as nothing more than background in the opening crawl, just like C-3PO is all beat up and dirty for reasons we never learn. The characters aren’t impressed by everything around them so the film doesn’t need to be either and the conversational nature of the dialogue, revealing fantastic things in a matter of fact way, always gets to the point. There may be so much about this universe that isn’t found within the widescreen frame and so many questions about it all even though it’s probably futile to expect total logic from this but so much of what’s there allows us to fill in the blanks. The script, credited to Lucas, slices what we need to know down to its essentials while never getting too lost in all the fantasy jargon even with his fetish for lots of numbers referenced in dialogue whether the Stormtrooper named TK-421 who won’t respond or the new BT-16, whatever it is, that’s apparently quite the thing to see. The script was also reportedly worked on by AMERICAN GRAFFITI co-writers Willard Hyuck and Gloria Katz so the Luke-Leia-Han triangle plays a little as a revisit of the main relationships in their screenplay for the 1975 Stanley Donen film LUCKY LADY, another attempt at an old time pastiche which did more than just imply what was going on between the threesome of stars Liza Minnelli, Gene Hackman and Burt Reynolds, it literally put all of them into bed together. STAR WARS of course keeps the sex out of things and sticks to the enjoyable banter, a sense of carefree innocence in the air during the final moments as if these three will be perfect together the way they are.

As director, Lucas always operates with an eye towards the details whether all those ever-present Stormtroopers, the eternal mystery of the lookalike droid behind C3PO in the opening moments or even how the revolutionary Ben Burtt sound work makes R2-D2 a fully fleshed out character. But even when on the surface the action should be generic like the endless running around the Death Star, the scenes always have an extra kick whether laughs at just the right moment, how much the actors play the tone just right or just the unrelenting sense movement that never lets the tempo slow down for too long. Even the mayhem is placed correctly up against the eerie quiet of other moments, particularly when focusing on Obi-Wan Kenobi’s journey around the massive space station in the way he takes care of the tractor beam or the simple calm of finding Vader standing before him, waiting for the inevitable. The design of the Death Star and the coldness of the corridors that seem to go on forever add to that feel while each spaceship design has just the right amount of character to make us want to see what each of them can do.

This version of outer space is a different yet recognizable universe, with elements like the funhouse quality of all the creatures in the cantina scene, full of touches that add to the old movie tropes whether from old westerns or CASABLANCA and up against all that the special effects are groundbreaking, yes, but the way the rhythm of the film itself responds to it so to create this universe means there’s not a wasted frame, nothing is missing. It’s not that the film ever has a huge amount on his mind—buried under the intellectualism of the Eisensteinian cutting style and not so hidden left wing slant to the rebels in their fight against the evil Empire it’s about the emotion of the moment, a reminder that sometimes what the best films can do to give us this feeling, itself a kind of propaganda to inform us not through speech but the pure cinematic combination of sound and image. Even down to the final bars of the closing credits where the spectacular John Williams score, itself a tribute to both classical music and all sorts of Hollywood adventure films of the past seems to quote a passage from Alfred Newman’s “Street Scene” overture at the start of HOW TO MARRY A MILLIONAIRE or the use of the Fox CinemaScope extension in its fanfare at the beginning as a way to definitively announce that this is a larger than life Movie just like they used to make, at least in our dreams.

In the end, it feels like STAR WARS is about making the decision to go off and live the life which helps you comes to terms with that destiny, letting go of the past that terrifies you to figure out who you really are. In a way, Luke’s decision to turn off his targeting computer before his final shot at the Death Star’s exhaust port is an odd case of the film rejecting the technology it wouldn’t exist without yet it’s still the perfect conclusion to his arc here, to figure out the world by using whatever lies within yourself to make that leap forward. And even with all this technology to produce the visual effects the film plays as effortless as it should and the ever-present charm comes out of that feeling. That’s the masterful exhilaration of the final Death Star battle which is all about that pacing and how the unrelenting rhythm gets into our heads, the excitement that grows with every single new shot which allows it to be analyzed endlessly right down to the power of that cut from Peter Cushing’s Tarkin to the very last second of the Death Star right before the explosion. It’s a feeling we never get rid of that matters more than plot or where those revelations are going to lead ever could, always moving forward towards destiny.

The lead performances match the tone perfectly in all their excitement with the uncomplicated boyishness of Mark Hamill, the adroit fearlessness of Harrison Ford, the Hawksian determination of Carrie Fisher who also brings a touch of regality to the dialogue she plays with Peter Cushing, rolling his r’s like nobody’s business and having a glorious time in his ice-cold ferocity. Alec Guinness is particularly enjoyable to watch as he bounces off Hamill and Ford, his bemused nature bringing all the weight in the world to even the smallest of moments, even if it never quite brings out the desert eccentric ‘Ben’ Kenobi allegedly is. But this really doesn’t matter, not when his very presence adds so much and his final smile to Luke as he goes off to deal with the tractor beam provides all the human connection the film needs. Even the small roles pop like Richard LeParmentier in his run in with Vader as the cocky Admiral Motti, the weathered nature of Phil Brown and Shelagh Fraser as Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru but also particularly a few of the rebels during the climax who have stayed in our heads all these years and seem to develop full characterizations while doing nothing but spout battle jargon, each one achieving a certain kind of immortality in their X-wing fighters.

STAR WARS famously opened at Grauman’s Chinese on May 25, 1977, the day after a celebration at the theater to commemorate its fiftieth anniversary which included a special showing of KING OF KINGS. The symbolism of this is tough to overstate, almost dividing much of film history itself into what came before STAR WARS and what has followed after. And who knows what filmmaking is even going to be once we pass the fifty year mark on this one. Of course, just as STAR WARS, the film called simply STAR WARS, doesn’t really have a beginning it also doesn’t really end, merely concluding with this victory over the Evil Galactic Empire. Sure there was more to come but it’s as if by this point George Lucas really has embraced his destiny with this achievement, the blonde in the white T-Bird far in the past, and after that nothing else needs to be said. In the 70s up until STAR WARS was released it seemed like pretty much every ending was downbeat, except for maybe JAWS, ROCKY and FREEBIE AND THE BEAN. But after this and the rapture of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND soon after those endings no longer seemed of the time, as if it was suddenly a film’s job to remind us that everything was going to be ok and nothing more. Not that it was the fault of these individual films, mind you, but it did happen. And even now the film that goes by the name STAR WARS plays as a reminder of how we always need to move forward, no matter how afraid we are of what might happen. Although we should still remember that happy endings are always happy until they’re not. Because even destiny doesn’t necessarily lead us where we think it will. No matter how exhilarating the trip is.

Saturday, November 30, 2019

One At A Time

With Martin Scorsese’s THE IRISHMAN fresh on the brain, it’s impossible not to think of certain other late films by great directors which feel like summations of everything they’ve ever said and done. Something like THE MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE wasn’t really John Ford’s last film but it very much represents the last word of everything he was saying, just as THE IRISHMAN feels like the last statement on every Scorsese protagonist who was by himself at the end, isolated from everyone and everything he ever knew. Of course, there will likely be more Scorsese films to come, hopefully for years, but as is forever inevitable, sometimes the end is the end. And final films are usually not meant to be final films. For John Huston, THE DEAD can certainly be read as a coda to his long career but with John Cassavetes it was BIG TROUBLE, a favorite of mine but not at all one of his personal projects and one he reportedly disowned, unhappy it would be thought of as his final film. Plus there’s Alfred Hitchcock and FAMILY PLOT, Howard Hawks and RIO LOBO, Tony Scott and UNSTOPPABLE, Blake Edwards and SON OF THE PINK PANTHER just to name a few and it’s easy to read finality into any of these to look for some sense of completion. It’s what we do. In reality, these were likely directors still hoping to make more for as long as humanly possible which is how it should be.

Of course, BUDDY BUDDY will always be known as the final film directed by the great Billy Wilder so it’s hard not to look at it as the end of something significant. A comedy so cynical that there’s nowhere really to go once it’s over, it practically qualifies as a final, definitive statement of a world view. How much it succeeds as comedy is open to debate. An instant box office failure when released in December 1981, Wilder himself was never that kind towards it in later interviews and by now the very use of the title has become a short hand for an unfortunate late film, the sort of thing Quentin Tarantino says he wants to avoid by quitting after ten movies. BUDDY BUDDY has the potential elements for classic Wilder and even contains a few surface similarities to his 1974 remake of THE FRONT PAGE—a reunion with Jack Lemmon & Walter Matthau, a story based on previously filmed material, much of the film taking place in a single location and the two were even both released at Christmas. THE FRONT PAGE, likely no one’s favorite Wilder film either, did a little better but between the two of them it’s clear that by this point even Wilder was at the mercy of projects that could be easily packaged by an interested studio. Nobody seems to like BUDDY BUDDY. I sort of do, maybe because I really want to. That doesn’t mean I don’t see problems but there are still a few laughs and I could even look at its finality as a stripped down view of the world and humanity done by a director using two of his favorite actors as vehicles to deliver that verdict. And besides, since this is the end it matters that much more. As Rene Belloq would state with confidence, this is history.

A hitman named Trabucco (Walter Matthau), hired to eliminate witnesses in a massive land fraud scandal, arrives in Riverside, Califonia, where the final witness, a mob stool pigeon, is about to testify that day. As Trabucco arrives at the Ramona Hotel where he has a nice view of the courthouse steps waiting for him, television censor Victor Clooney (Jack Lemmon) checks in to the room next door hoping to reconcile with his wife Celia (Paula Prentiss) who has run off with Dr. Hugo Zuckerbrot (Klaus Kinski) head of the nearby sex institute the Zuckerbrot Clinic (“Ecstasy is Our Business”). When Celia refuses to meet with him Victor quickly and unsuccessfully tries to kill himself, leaving Trabucco forced to deal with his disruptive neighbor as he desperately tries to prevent anything which will bring attention to the job that has to get done.

A remake of the Francis Veber-scripted French farce L’EMMERDEUR (released in the U.S. as A PAIN IN THE A--), BUDDY BUDDY is short and slight plus not as funny as it should be but there is a certain degree of integrity to its cynicism. Written with longtime collaborator I.A.L. Diamond, this was Wilder’s first association with MGM since co-writing the masterpiece NINOTCHKA back in 1939 and it would be nice to think the comedy is in that tradition but there’s not much trace of the Golden Age that Wilder became a legend in. The plotting doesn’t exactly stand up to close scrutiny even for a farce and it’s a sour film, with thinly drawn, unlikable characters living in a world that the director doesn’t seem to have much use for anymore, fed up with whatever it’s become with a dead body followed by the sight of Walter Matthau driving a milk delivery truck reading “FEEL BETTER LIVE LONGER” one of the better jokes. Jack Lemmon’s television censor Victor Clooney is an uptight prig apparently known as the ‘Iron Duke’ at CBS, a nickname I’ll bet he gave himself, who apparently left his wife and family years earlier only to now be dumped by the second wife with nothing to show for that marriage, happy to tell a total stranger he’s been throwing up because his wife left him. The implication to it all is that he hasn’t spent a second of his life actually living which suggests a more intriguing characterization than we ever get. Much of his backstory is revealed in one short driving scene and it’s about all we get of the character, just that and his suicide attempts and all the pleading for his wife to come see him. The way the film is laid out plays as if he’s the sort of putz who Wilder can’t stand while the Matthau hitman is more his speed. All we ever know about his past is a vague reference to being married, as he puts it, “Once. But I got rid of her. Now I just lease,” and everything about him is revealed by his habit of only buying one cigar at a time, never planning anything too far ahead, never letting a sliver of emotion slip through.

The humor in BUDDY BUDDY is not always as sharp as it should be, looking for some sort of middle ground between dark comedy and sex farce that all feels slightly outdated for ’81, with what I imagine was the unique sound at the time of Walter Matthau calling Jack Lemmon ‘shithead’ with Paula Prentiss musing on how the sex doctor she’s sleeping with will help her achieve ‘the ultimate orgasm’. The bulk of the plot is all contained within just a few hours, almost in real time and it’s so tight that there isn’t much chance for enough plot to actually happen but it still never moves all that fast and if the pace were picked up to a certain extent it might barely reach feature length. More than just the hitman plotline it’s really about the two leads, Matthau all stoic and Lemmon taking things to the nightmare end of his flopsweat persona, but the characterizations never get too deep and the way Trabucco acts annoyed towards Clooney you can barely believe that these guys actually just met. Incidentally, the film opened a week apart from the John Belushi-Dan Ackroyd NEIGHBORS, another darkly comic teaming mostly set in one location, but while a Lemmon-Matthau version of that film doesn’t sound very intriguing, the daydream of putting those other two stars into BUDDY BUDDY seems to offer a number of possibilities either way you’d go with that casting and feels like it would have lots of ways to expand on the characterizations.

It’s all set in a bland looking southern California where everyone is already slightly skeptical of whatever they’re being told with a flat, stop-start feel to the rhythm of scenes and the closest thing to any real visual consistency is the way the film seems to place as many palm trees into the frame as possible as though looking for some sort of respite from the stifling nature of it all. Many of the side details are more weird than funny whether the hippie celebrating the birth of his son named ‘Elvis Jr.’ as he gives celebratory joints to cops, the Sitar music that accompanies the scenes at the sex institute (which seems mostly populated by senior citizens, whatever we’re supposed to make of that) and Klaus Kinski dialogue about how “premature ejaculation means always having to say you are sorry”. The extensive rearscreen projection during driving scenes is one of those indicators that make it feel Wilder chose the project because of how logistically simple the production would be along with a Lalo Schifin score which is energetic but still feels like it would be more at home in a mid-70s ABC movie of the week. But even that doesn’t mean I don’t gladly sit through the end credits each time I watch the film and the pure feel of nasty defiance found in BUDDY BUDDY gives the film a certain integrity, even if not enough of the dialogue has the old Wilder-Diamond zing like the orderly at the sex clinic who protests when a woman about to have a baby arrives saying, “We don’t deal with the finished product here!” But the mere sight of Walter Matthau’s annoyance carries it far and the ninety-ish minutes go by in a flash, the work of someone maybe not at their best but always aware of how this should go together.

At one point Jack Lemmon buys a bunch of lighter fluid with the plan to light himself on fire and yells out, “Apocalypse now!” which is actually one of the better lines so there are scattered laughs and bits of business among the ones that don’t work but, in the end, BUDDY BUDDY feels like nothing more than a view of the world by men of a certain age looking back on what’s been accomplished in a life to think when all is said and done the answer is to say, well, fuck it. Why not just shoot somebody, what does anything really matter? The sex wasn’t worth it, you were probably bad at it anyway, the second wife didn’t solve all your problems and now there’s nowhere else to go with the wedding ring that’s been melted down into a charm necklace in the shape of her new man’s giant cock serving as a symbol for it all. There’s still more potential in the various plot elements like the Clooney marriage that the film doesn’t have time for so it feels like a waste to strand the great Paula Prentiss in such a one-note bitch role which I wonder if she took simply because it was Wilder. The end of BUDDY BUDDY is a message that you can’t fully escape the annoyances of the world no matter how far you run so why the fuck not just be your true self. And somewhere in this revelation is a kind of optimism. Billy Wilder lived just over twenty years after BUDDY BUDDY was released so for him it wasn’t really the end. Just the end of all we were ever going to learn from him through his films.

Probably the most consistent pleasure found in the entire film is the incisiveness of Walter Matthau who gets laughs from lines that don’t deserve it, continually showing what he can do with just a few words or no words at all, if necessary. The hitman is probably a better part but Jack Lemmon is simply a little too much in comparison, no subtlety or shading and can’t quite get the laughs out of a character who is a little too pathetic a little too much of the time. He’s apparently playing 48 for some reason, looking not a day younger than the 56 he was but as much as I love and miss Lemmon he just never gets the right moments here for his performance to fully come together. Incidentally, this was the last film Lemmon and Matthau appeared in together until they both turned up separately in Oliver Stone’s JFK followed by their final run of films together in the 90s. Klaus Kinski, who hated this movie, feels more robotic than comedic in almost every line delivery but it’s still enjoyable bizarre to watch him here anyway, making me wish there were more scenes with him and Paula Prentiss who is energetic all through her scenes but she’s still isn’t very much for her to do and it’s too bad. The familiar faces that turn up include Dana Elcar as the police captain, Miles Chapin from Allan Arkush’s GET CRAZY as the hotel bellhop, Ed Begley, Jr. as one of the cops guarding the courthouse plus Joan Shawlee from SOME LIKE IT HOT and THE APARTMENT who plays the receptionist at the Zuckerbrot Clinic.

And since I mentioned him here I may as well recount the story of the time at a party where I met Ed Begley, Jr. and while standing around in conversation for some reason the name Billy Wilder came up. “I worked with Billy Wilder,” he offered to which I piped in with, “Yeah! You were in BUDDY BUDDY!” At which point Begley looked astonished, hopped back a step and said, “How did you know that?” I think my answer was something like, “Because you’re Ed Begley, Jr. And you were in BUDDY BUDDY.” What I’m saying is, in this life we take our immortality where we can get it. L’EMMERDEUR was remade in France yet again in 2008 followed by a Bollywood version in 2012 and it’s a good question why this particular storyline needs to be revisited by anyone this many times. Maybe the recent remakes account for what may be certain rights issues since BUDDY BUDDY isn’t easy to see at all right now except through, um, certain disreputable means; maybe this is why the good people at Warner Archive haven’t released it on disc since MGM titles usually fall under their domain. But regardless BUDDY BUDDY, through the laughs it does have along with getting to see Lemmon and Matthau bicker together is at least one more Billy Wilder film. And with a hitman protagonist who, at the end, is isolated from everyone and everything he ever knew, it’s as much about death as THE IRISHMAN and, just as that film does, the last image of BUDDY BUDDY offers one final, definitive statement about that glimpse of death from the specific point of view of the great director who made it. None of which is a question of whether these films are good or bad but simply what they are. And if that’s not cinema, nothing is.

Some Men Have Strange Desires

If we had more time right now I’d get into it. Things have just been a little crazy lately. What’s good seems to remain just out of reach and I can’t tell which way things are going or what may be coming. That’s the sort of year it’s been, maybe the sort of future it’s going to be. So for now, it’s time for a western. Those usually help. And even when the New Hollywood emerged as the 60s turned into the following decade the western still wasn’t gone just yet. John Wayne, freshly an Oscar winner for one of those, still had a few years to go at that point and his final film for the great Howard Hawks, RIO LOBO, came out in December of 1970. LITTLE BIG MAN, even if it qualifies as a revisionist western, was one of the top grossing films of that year. The genre of course also helped turn Clint Eastwood into a star and at this point no one knew DIRTY HARRY was going to overtake all that so the run of starring vehicles which landed between his Leone films and the introduction of Inspector Callahan is an intriguing batch, as if they’re all part of a top spinning to determine exactly which way his stardom was going to go. HANG ‘EM HIGH turns up on TV more than it probably deserves and PAINT YOUR WAGON is infamous as a prime example of Hollywood waste but there’s also his directorial debut PLAY MISTY FOR ME as well as the pre-Harry films he made with that film’s director Don Siegel: COOGAN’S BLUFF, THE BEGUILED and TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA, the last of which is also a western and, released in June 1970, in some ways it’s not anything but a western but pairing him with someone like Shirley MacLaine takes the film to a different place in the genre which helps it stand out. It may not be the sort of classic HIGH PLAINS DRIFTER would later become and it definitely isn’t Leone but the enjoyable TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA is just unique enough to make it a fun discovery. If anything, it’s a reminder to keep an open mind towards the next thing that might be coming which is pretty much what I need right now.

Riding through Mexico, a former Civil War solider named Hogan (Clint Eastwood) comes across a woman being terrorized by several bandits ready to kill her. Hogan dispatches them quickly enough but is soon surprised to learn that the woman is in fact a nun named Sara (Shirley MacLaine) who has been helping Mexican revolutionaries in fighting the French that she claims are after her. Since Hogan has already made a deal to help out the revolutionaries in exchange for half the French’s treasury if they are successful, he agrees to escort Sister Sara to them. But her unexpected behavior reveals her to be a somewhat unusual nun and it soon becomes clear that their journey will not be as easy as Hogan first anticipated.

TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA is the sort of star vehicle where by a certain point you realize you’re paying more attention to what the leads are doing than the plot which I honestly always glaze over on. Eastwood and MacLaine are definitely fun to watch together even if the two of them feel like they’re bouncing off each other during their scenes more than developing any real chemistry, the banter keeping things going until whatever’s being argued over is dropped and they just move on to the next scene. But even if no real fireworks develop between them it always feels assured as a film and photographed by Gabriel Figueroa (credits include THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL as well as KELLY’S HEROES, also with Clint, which came out the same year) it contains some of the most elegant camerawork found in anything ever directed by Don Siegel, giving the two stars some wonderful close-ups and making full use of the Mexican locations. There’s always a complexity to the shots which visually takes it far beyond some of the director’s other films from the period which can have too much of a ‘Filmed in Universal City’ feel even when they’re shot on location—these are likely distant memories of MADIGAN poking around in my head. DIRTY HARRY would be shot by Bruce Surtees (camera operator on TWO MULES) and in some ways it’s deliberately one of the ugliest looking films ever but in the case of TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA there’s a beauty to the way it places its two leads against the landscape, offering its own assistance to the growing relationship between them, as if the film itself is looking for ways to keep them in the frame together.

The visual beauty of the Mexican landscape glimpsed in the opening credits is combined with the pure heavenliness that is the Ennio Morricone score which of course is a slight extension of what that composer did for the spaghetti westerns a few years earlier. With a few cues utilized by Tarantino later on for DJANGO UNCHAINED, it provides the expected arch commentary but also takes the threadbare story to a different level, allowing us to accept the heavenly intervention at work even if no one onscreen can, providing this film with its own tapestry of searching for deliverance, however that may come. If I’m being totally honest the power of that music makes me want to like TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA even more than I already do but from the very first notes heard during the Universal logo that’s where much of the serenity comes from. The film seems willing a surprising number of times to just sit back and let some cues play out during transitions, looking beyond the fairly simple plot towards something else. It’s just what you want from Morricone, the right amount of quirk and beauty combined into something totally unique which makes the film more than it would have been otherwise.

Maybe it’s best described as the sort of movie where the sounds and images are among the best things about it so as a result the most notable aspects of the film may be what it might have been. The screenplay was by Albert Maltz, one of the Hollywood Ten and also a writer on films like THIS GUN FOR HIRE and THE NAKED CITY, from a story by the great Budd Boetticher who had hoped to direct for himself (and reportedly no fan of the film that was eventually made). Elizabeth Taylor was also intended to co-star with Clint but the deal apparently fell apart when she insisted on the film being shot in Spain where Richard Burton was working so Universal cast Shirley MacLaine who unlike Taylor wouldn’t pass as a Mexican (hey, it was a different time) but she was the star the studio wanted. It certainly changes whatever the film was originally going to be but MacLaine’s off-center screen presence finds the balance between the comic grouchiness of Clint and the more serious revolutionary elements the film really only has passing interest in. She brings needed gravity to what is otherwise a lark while playing off of the film’s wry amusement towards the increasingly perplexing way this nun acts and how much sense it makes when revealed why. “The lord grants dispensations in such circumstances” is what she says a number of times to allow for their transgressions while the phrase “Everybody’s got a right to be a sucker once” also gets repeated and the film is ultimately about finding the middle ground between the two to keep going, to give into the fear of losing yourself while with another person, which sort of makes sense for a movie where the two stars don’t totally click in a romantic sense.

It’s a sort of western AFRICAN QUEEN in a way but for long stretches the plot barely seems to matter much at all, veering between the two of them bickering and the genuinely serious glimpse at the revolution in Mexico against the French that it brushes past, putting off actual movement in the main plot until after the hour mark. Even the title barely matters since Sister Sara trades her mule for a burro fairly early, making nonsense of the phrase unless Hogan himself is supposed to be the second mule being dragged along. All this maybe makes it more of a buddy movie than a love story in the closeness that develops even though roughly half of the film is just Eastwood and MacLaine, no one else to share the screen with. But it rarely drags, with the most drive coming during a prolonged sequence in the middle section involving Hogan being hit with an arrow by an Indian attack that Sister Sara has to remove followed by the matter of blowing up a bridge to keep a train with supplies from getting through. It all culminates in some very impressive miniature work and putting aside that it’s hard for me to dislike any film with a spectacular train crash done this way the film still always remembers to be about the two of them so it becomes maybe even something deeper than just a love story, but about two people who respect each other in spite of everything and, ultimately, need each other no matter what plans they otherwise made. But spending so much time with just the two leads still doesn’t allow for very much variety; one expects them to run into an old friend of Hogan’s played by some familiar character actor to liven things up which wouldn’t have been a bad idea and, as it is, there are barely any significant supporting characters at all, with most of the other actors in and out in one scene, either adversaries to be gunned down or cohorts ready with information. The third billed actor in the entire film is Manolo Fabregas playing the Colonel in charge of the Mexican revolutionaries that Hogan is looking to rendezvous with and he has a fair amount of screen time in the second half but even his character is entirely in service to the two leads, everyone else pretty much forgotten by the end.

Which still makes sense since Clint’s Hogan is a loner, sort of a Bogart in CASABLANCA-type more interested in the profit than the cause and surprisingly the film, set in Mexico with two white leads that apparently matter more than anyone who actually lives in the country, never asks him to change his mind. Hogan’s dream is to go to San Francisco, where UNFORGIVEN’s William Munny supposedly wound up after the end of that film, but his desire to stay on his own is upended by Sister Sara and a few of the most unexpected moments in the film gives us a rare look at a Clint Eastwood character who’s at a genuine loss for words thanks to her. In comparison, Shirley MacLaine is, well, the Shirley MacLaine-type much of the time but when she finally takes action the actress finds the needed gravity to the moments which help remind us that there actually is a plot going on and they’re some of the best moments in the entire film. TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA is a good popcorn movie and I’m not sure it’s anything more than that but there’s nothing wrong with being that either. Even when Hogan and Sara hatch a plan near the end against the French to break into their fortress, the climax has a little too much of a second unit feel when the battle breaks out, losing the stars in the mayhem for much of it except for when Clint gets in some Gatling gun action but at least some of the explosions are pretty cool. TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA has that but also remembers to find the grace notes to pause among the landscape and the music with a final shot that serves as a reminder of what it means to stay with another person against your better judgement while still never entirely losing yourself and who you really are.

Because of all this it comes down to the two leads and how they work off each other to make them evenly matched so instead of sparks that come it’s an easygoing camaraderie which pays off whatever’s been growing between them throughout the film. Clint Eastwood combines the coolness of his spaghetti western persona with the patience of having to deal with this nun he can’t quite understand and considering it would be several decades before he would again co-star with an actress of equal stature (all respect to the likes of Jessica Walter, Tyne Daly, Sondra Locke and Patricia Clarkson) he seems totally comfortable sharing the screen, always aware that just his presence in the frame can be what’s needed. Meanwhile, Shirley MacLaine and her physicality are always engaged with the setting, displaying expert comic timing when needed and holding back her true self until just the right moment so when the façade is ripped away she plays the scenes as barely moving a muscle to underline the gravity of the moment and how there will be no arguing with her.

In his autobiography “A Siegel Film” the director seems pleased with how TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA turned out even though producer Martin Rackin took control for the final edit but mentions with some confidence that he had shot the film to be cut a certain way regardless. Shirley MacLaine, meanwhile, later on said that she loved Clint even though he was a republican and, yes, this is a struggle many of us have had through the years. But maybe this film is really about looking beyond that surface to what can develop in spite of everything, the way Hogan and Sister Sara discuss whether certain things that happened were in fact miracles or just simple accidents. Which is often a good question to ask as you move through life, to understand what led to those domino effects that changed things for you irrevocably, with no way to turn back. Maybe there was a reason. Or maybe there is no answer and the decision of whether you’re going to be alone through all this is up to you. Even westerns can ask these questions, even if that turns out to be only a minor element of the film in the end. Maybe I respond to the beauty of music by Ennio Morricone so much because it sounds like fate, the sounds of what you can potentially discover as you ride through life, trying to find the answers to the life you really desire and if it’s really possible to ever find that without giving up your greatest dreams.

Riding through Mexico, a former Civil War solider named Hogan (Clint Eastwood) comes across a woman being terrorized by several bandits ready to kill her. Hogan dispatches them quickly enough but is soon surprised to learn that the woman is in fact a nun named Sara (Shirley MacLaine) who has been helping Mexican revolutionaries in fighting the French that she claims are after her. Since Hogan has already made a deal to help out the revolutionaries in exchange for half the French’s treasury if they are successful, he agrees to escort Sister Sara to them. But her unexpected behavior reveals her to be a somewhat unusual nun and it soon becomes clear that their journey will not be as easy as Hogan first anticipated.

TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA is the sort of star vehicle where by a certain point you realize you’re paying more attention to what the leads are doing than the plot which I honestly always glaze over on. Eastwood and MacLaine are definitely fun to watch together even if the two of them feel like they’re bouncing off each other during their scenes more than developing any real chemistry, the banter keeping things going until whatever’s being argued over is dropped and they just move on to the next scene. But even if no real fireworks develop between them it always feels assured as a film and photographed by Gabriel Figueroa (credits include THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL as well as KELLY’S HEROES, also with Clint, which came out the same year) it contains some of the most elegant camerawork found in anything ever directed by Don Siegel, giving the two stars some wonderful close-ups and making full use of the Mexican locations. There’s always a complexity to the shots which visually takes it far beyond some of the director’s other films from the period which can have too much of a ‘Filmed in Universal City’ feel even when they’re shot on location—these are likely distant memories of MADIGAN poking around in my head. DIRTY HARRY would be shot by Bruce Surtees (camera operator on TWO MULES) and in some ways it’s deliberately one of the ugliest looking films ever but in the case of TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA there’s a beauty to the way it places its two leads against the landscape, offering its own assistance to the growing relationship between them, as if the film itself is looking for ways to keep them in the frame together.

The visual beauty of the Mexican landscape glimpsed in the opening credits is combined with the pure heavenliness that is the Ennio Morricone score which of course is a slight extension of what that composer did for the spaghetti westerns a few years earlier. With a few cues utilized by Tarantino later on for DJANGO UNCHAINED, it provides the expected arch commentary but also takes the threadbare story to a different level, allowing us to accept the heavenly intervention at work even if no one onscreen can, providing this film with its own tapestry of searching for deliverance, however that may come. If I’m being totally honest the power of that music makes me want to like TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA even more than I already do but from the very first notes heard during the Universal logo that’s where much of the serenity comes from. The film seems willing a surprising number of times to just sit back and let some cues play out during transitions, looking beyond the fairly simple plot towards something else. It’s just what you want from Morricone, the right amount of quirk and beauty combined into something totally unique which makes the film more than it would have been otherwise.

Maybe it’s best described as the sort of movie where the sounds and images are among the best things about it so as a result the most notable aspects of the film may be what it might have been. The screenplay was by Albert Maltz, one of the Hollywood Ten and also a writer on films like THIS GUN FOR HIRE and THE NAKED CITY, from a story by the great Budd Boetticher who had hoped to direct for himself (and reportedly no fan of the film that was eventually made). Elizabeth Taylor was also intended to co-star with Clint but the deal apparently fell apart when she insisted on the film being shot in Spain where Richard Burton was working so Universal cast Shirley MacLaine who unlike Taylor wouldn’t pass as a Mexican (hey, it was a different time) but she was the star the studio wanted. It certainly changes whatever the film was originally going to be but MacLaine’s off-center screen presence finds the balance between the comic grouchiness of Clint and the more serious revolutionary elements the film really only has passing interest in. She brings needed gravity to what is otherwise a lark while playing off of the film’s wry amusement towards the increasingly perplexing way this nun acts and how much sense it makes when revealed why. “The lord grants dispensations in such circumstances” is what she says a number of times to allow for their transgressions while the phrase “Everybody’s got a right to be a sucker once” also gets repeated and the film is ultimately about finding the middle ground between the two to keep going, to give into the fear of losing yourself while with another person, which sort of makes sense for a movie where the two stars don’t totally click in a romantic sense.

It’s a sort of western AFRICAN QUEEN in a way but for long stretches the plot barely seems to matter much at all, veering between the two of them bickering and the genuinely serious glimpse at the revolution in Mexico against the French that it brushes past, putting off actual movement in the main plot until after the hour mark. Even the title barely matters since Sister Sara trades her mule for a burro fairly early, making nonsense of the phrase unless Hogan himself is supposed to be the second mule being dragged along. All this maybe makes it more of a buddy movie than a love story in the closeness that develops even though roughly half of the film is just Eastwood and MacLaine, no one else to share the screen with. But it rarely drags, with the most drive coming during a prolonged sequence in the middle section involving Hogan being hit with an arrow by an Indian attack that Sister Sara has to remove followed by the matter of blowing up a bridge to keep a train with supplies from getting through. It all culminates in some very impressive miniature work and putting aside that it’s hard for me to dislike any film with a spectacular train crash done this way the film still always remembers to be about the two of them so it becomes maybe even something deeper than just a love story, but about two people who respect each other in spite of everything and, ultimately, need each other no matter what plans they otherwise made. But spending so much time with just the two leads still doesn’t allow for very much variety; one expects them to run into an old friend of Hogan’s played by some familiar character actor to liven things up which wouldn’t have been a bad idea and, as it is, there are barely any significant supporting characters at all, with most of the other actors in and out in one scene, either adversaries to be gunned down or cohorts ready with information. The third billed actor in the entire film is Manolo Fabregas playing the Colonel in charge of the Mexican revolutionaries that Hogan is looking to rendezvous with and he has a fair amount of screen time in the second half but even his character is entirely in service to the two leads, everyone else pretty much forgotten by the end.

Which still makes sense since Clint’s Hogan is a loner, sort of a Bogart in CASABLANCA-type more interested in the profit than the cause and surprisingly the film, set in Mexico with two white leads that apparently matter more than anyone who actually lives in the country, never asks him to change his mind. Hogan’s dream is to go to San Francisco, where UNFORGIVEN’s William Munny supposedly wound up after the end of that film, but his desire to stay on his own is upended by Sister Sara and a few of the most unexpected moments in the film gives us a rare look at a Clint Eastwood character who’s at a genuine loss for words thanks to her. In comparison, Shirley MacLaine is, well, the Shirley MacLaine-type much of the time but when she finally takes action the actress finds the needed gravity to the moments which help remind us that there actually is a plot going on and they’re some of the best moments in the entire film. TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA is a good popcorn movie and I’m not sure it’s anything more than that but there’s nothing wrong with being that either. Even when Hogan and Sara hatch a plan near the end against the French to break into their fortress, the climax has a little too much of a second unit feel when the battle breaks out, losing the stars in the mayhem for much of it except for when Clint gets in some Gatling gun action but at least some of the explosions are pretty cool. TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA has that but also remembers to find the grace notes to pause among the landscape and the music with a final shot that serves as a reminder of what it means to stay with another person against your better judgement while still never entirely losing yourself and who you really are.

Because of all this it comes down to the two leads and how they work off each other to make them evenly matched so instead of sparks that come it’s an easygoing camaraderie which pays off whatever’s been growing between them throughout the film. Clint Eastwood combines the coolness of his spaghetti western persona with the patience of having to deal with this nun he can’t quite understand and considering it would be several decades before he would again co-star with an actress of equal stature (all respect to the likes of Jessica Walter, Tyne Daly, Sondra Locke and Patricia Clarkson) he seems totally comfortable sharing the screen, always aware that just his presence in the frame can be what’s needed. Meanwhile, Shirley MacLaine and her physicality are always engaged with the setting, displaying expert comic timing when needed and holding back her true self until just the right moment so when the façade is ripped away she plays the scenes as barely moving a muscle to underline the gravity of the moment and how there will be no arguing with her.

In his autobiography “A Siegel Film” the director seems pleased with how TWO MULES FOR SISTER SARA turned out even though producer Martin Rackin took control for the final edit but mentions with some confidence that he had shot the film to be cut a certain way regardless. Shirley MacLaine, meanwhile, later on said that she loved Clint even though he was a republican and, yes, this is a struggle many of us have had through the years. But maybe this film is really about looking beyond that surface to what can develop in spite of everything, the way Hogan and Sister Sara discuss whether certain things that happened were in fact miracles or just simple accidents. Which is often a good question to ask as you move through life, to understand what led to those domino effects that changed things for you irrevocably, with no way to turn back. Maybe there was a reason. Or maybe there is no answer and the decision of whether you’re going to be alone through all this is up to you. Even westerns can ask these questions, even if that turns out to be only a minor element of the film in the end. Maybe I respond to the beauty of music by Ennio Morricone so much because it sounds like fate, the sounds of what you can potentially discover as you ride through life, trying to find the answers to the life you really desire and if it’s really possible to ever find that without giving up your greatest dreams.

Saturday, September 21, 2019

Captive On The Carousel Of Time

The following contains extensive spoilers about ONCE UPON A TIME…IN HOLLYWOOD.

Sharon Tate did die. We already know this. She died and so did Jay Sebring and the others who were at the house up on Cielo Drive with them and then the LaBiancas across town the next night. We know all this. And when I look at certain films that came from Hollywood over the next few years it’s hard not to see the darkness that has fallen over things because of that horrible event, because of the 60s ending then as the narrative became. Whether it’s the climax of BEYOND THE VALLEY OF THE DOLLS and how it was very much exploiting the events of that night, when Mark Rydell as gangster Marty Augustine in THE LONG GOODBYE takes a Coke bottle to the face of his angelic redhead girlfriend (played by Jo Ann Brody in her only screen appearance) it’s always Sharon Tate that I think of, Goldie Hawn sitting in her house up in the hills in the ’68-set SHAMPOO who has “this terrible feeling that something awful is going to happen” or, maybe most obviously, the way Roman Polanski chose to end CHINATOWN. All this becomes a part of these films just as much as it becomes a part of the town itself and whatever else ONCE UPON A TIME…IN HOLLYWOOD shows us, we can never forget that.

Sharon Tate also lived. She lived and she married Roman Polanski and she made THE FEARLESS VAMPIRE KILLERS with him and she also made movies like DON’T MAKE WAVES and THE WRECKING CREW, quickly becoming one of the most stunning examples of Hollywood beauty ever seen, while also displaying a comic potential that would have been truly wonderful to see develop in a life that is too often forgotten except for how it ended and nothing else. “Why don’t you stand over by the poster? So people will know who you are,” the ticket seller at the Bruin says to Margot Robbie as Sharon Tate, never even thinking that one day people might know her for anything else. I probably shouldn’t mention the girl I knew some years back who once went as Sharon Tate for Halloween and what that costume entailed.

This was a Los Angeles that I never knew since I wasn’t around yet but at least in ’69 my parents lived on Wilshire in a building that Sharon Tate would have driven past shortly after picking up that hitchhiker on her way to Westwood Village. The past stays with us and like it or not in Los Angeles some of those memories are going to be about all that driving, all those times on the freeway when we have to make our way back to the valley, the goddamn valley, so far up it feels like the end of the earth. Brad Pitt driving in this film is a wonderful thing to see as the day turns into night, with him speeding down Hollywood Boulevard, speeding down the freeway towards the exit with that Van de Kamp’s windmill waiting at the end of the Panorama City off-ramp as he heads for his trailer behind the Van Nuys Drive-In. All that driving in this film feels like it’s at least partly taken from Jacques Demy’s all-holy MODEL SHOP, a film actually released in ‘69 which also understood the rhythm those long days can fall into when you’re doing almost nothing but that driving, in no hurry to get anywhere. Cliff Booth is never in much of a hurry either. It’s just the way he drives.

ONCE UPON A TIME…IN HOLLYWOOD is a memory piece, the Tarantino version of Fellini’s AMARCORD, with its own history of what life was whether it’s what really happened or not, filtered through all those movies, TV shows and half remembered daydreams of billboards never seen again. Filtered through memories that never happened or maybe were never allowed to happen, which in this town can sometimes get mixed up. It takes its time like no other Tarantino film, the story of Hollywood cowboy actor Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), stuntman buddy/driver Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) as well as Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie), the rising star living next door to Rick on Cielo Drive and the long day each of them spend in February ’69 before the film jumps ahead to August 8th of that year when the only thing anyone on that street seems to know for certain is that it’s going to be another hot summer night. There are many things that make ONCE UPON A TIME…IN HOLLYWOOD as glorious as it is, vibrant through every moment yet elegiac in its recreation of this time with a tinge of sadness always hanging around the edge of the fame and is maybe more about love than any other film Quentin Tarantino has ever made, even if it’s a love you always worry might fade away like the end of a movie. In that sense, it’s about loss as well. It’s as close to pure joy as any film I’ve seen in a long time.